A treatment first used more than a century ago, that uses bacteria-killing viruses, is making a comeback in Australia and doctors hope it will help counter a growing crisis of antibiotic-resistant superbugs.

The Alfred hospital in Melbourne has become the first health service in Victoria to begin using the pioneering phage therapy, which involves utilising harmless viruses – known as bacteriophages – to kill germs in cases where traditional antibiotics have failed.

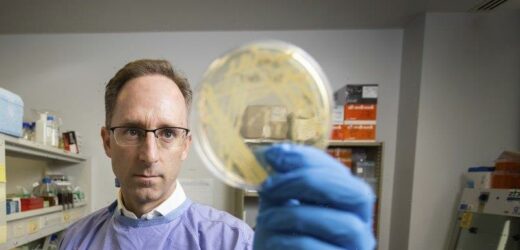

Professor Anton Peleg says phage therapy is used for an increasing number of patients on compassionate grounds.Credit:Paul Jeffers

Professor Anton Peleg, head of infectious diseases at The Alfred, said phage therapy was being used for an increasing number of patients battling potentially deadly superbugs, on compassionate grounds.

“They are patients with severe bacterial infections that are either life-threatening, or limb threatening, or function threatening, where they don’t have any other options left,” Peleg said. “It is a salvage treatment pathway.”

Discovered in 1917 by French-Canadian biologist Felix d’Herelle, bacteriophages are viruses that naturally evolved to prey on harmful bacteria. In the 1940s, the treatment largely disappeared, while the Western world shifted to antibiotics.

However, global interest in the therapy was reawakened recently by the rise of superbugs that have developed a resistance to antibiotics.

An artist’s illustration of a phage virus attacking bacteria.Credit:Getty Images

“We desperately need novel approaches to attack superbugs, approaches that are different to existing traditional antibiotics,” Peleg said.

Increasingly, phages are now being seen by some scientists as a potential complement or even an alternative to antibiotics, the overuse of which has contributed to increasing bacterial resistance and the advent of the superbug.

The Alfred’s phage therapy program began at the end of last year in partnership with Monash University’s Centre to Impact AMR (antimicrobial resistance), and has already been used to treat people who are severely ill with antibiotic-resistant infections, including patients with cystic fibrosis, who have endured years of chronic lung infections.

Others being referred to the program include those with drug-resistant prosthetic joint or limb infections and severe burn wounds.

“We recently received another referral for a woman with a recurrent urinary tract infection with terribly resistant bacteria,” Peleg said.

According to the World Health Organisation, antimicrobial resistance is a rising threat to global health, jeopardising decades of medical progress and transforming common infections into deadly ones. A UN report suggests yearly deaths from drug-resistant diseases could rise from 700,000 to 10 million in 30 years if no action is taken.

Phage therapy, which is most commonly provided intravenously, can be required for several months. Peleg said patients at The Alfred undergoing the treatment were monitored closely to evaluate the activity of the phage in their bodies.

Peleg said the treatment depended on accurate diagnosis of the bacterial strain causing infection and the phage required to fight it. With billions of different bacteria killing viruses in our natural environment – found in river systems, soil and sewage – sourcing the appropriate phage can be difficult.

To speed up this process, Peleg and his team spent the past four years collecting the most common bacteria that have caused infections at The Alfred. Among them is Staphylococcus aureus bacteria, also known as golden staph and pseudomonas.

The hospital also has an onsite translational phage lab, where staff scour environmental sources, identify phages, then test their activity with a combination of antibiotics. The phages are then produced and packaged into vials by an expert team at Monash University.

“We’ve been storing the most common bacteria causing infection at The Alfred and are looking for phage that have killing activity against those bacteria to develop a phage biobank,” Peleg said. “This allows us to have a cocktail of multiple phages, prepared to use for future patients with bacterial infections.”

University of Sydney microbiologist Professor Jon Iredell is on the front line of phage therapy in Australia and has used the treatment alongside other medications to treat dozens of patients in NSW since 2007. Among them are children, patients with golden staph or E. coli infections and people on life support.

He said phage therapy was gaining traction in Australia, with teams in Melbourne and Western Australia treating their first patients recently.

But Iredell said a lack of robust data and large-scale clinical studies had hindered advancements and understanding. In Australia, the treatment is still deemed experimental and is awaiting approval by the Therapeutics Goods Administration.

“It’s our job to be sceptical, and we have to make sure this is safe, but all the data suggests so far that it is safe when it is used properly and the phage is made properly,” Iredell said.

Australians wanting the treatment must fit strict eligibility criteria, including being referred to an infectious disease specialist, who can certify they are already using the appropriate treatment and more was needed.

Iredell and Peleg are part of a group of doctors working to develop a regulatory framework to use phage therapy nationally in the hope it will pave the way for big clinical studies in Australian hospitals.

Phage therapy has shown success in experimental cases overseas, including two patients in the US who recovered from intractable infections after being treated with genetically engineered bacteria-killing viruses.

In 2019, a teenager in the UK also made a remarkable recovery after being among the first patients in the world to be given a genetically engineered virus to treat a drug-resistant infection.

“All of us in the phage community often joke for every bacterial problem there is a phage solution because they’re the natural predators and since before humans evolved,” Iredell said. “Antibiotic resistant infections are one of the greatest risks to modern health infrastructure, and we need to act now.”

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article