‘I felt as if I’d arrived in hell’: £1m-a-year banker who was jailed in Enron scandal describes his journey from leafy Home Counties to US prison where he shared a cell with a crack dealer and a paedophile

Nothing about Giles Darby’s life as a £1 million-a-year City banker — the Hertfordshire home with swimming pool in three manicured acres, the first-class travel; the well-cut suit and chauffeur-driven car — could have prepared him for life in a harsh U.S. penitentiary.

‘The richer your life outside, the harder it is to be inside,’ observes Giles, one of the so-called NatWest Three, who was extradited to America and jailed there because of his entanglement in a £7 million fraud against the bank he worked for.

‘A tramp may go to prison and be grateful for a bed and a meal. But if you’re used to expense-account dinners and the bill is just irrelevant — you don’t even look at the cost of the wine — to be picking the meat from the undercarriage of a chicken carcass, eating ‘sewer trout’ or chewing a burger made entirely of gristle is a big comedown.’

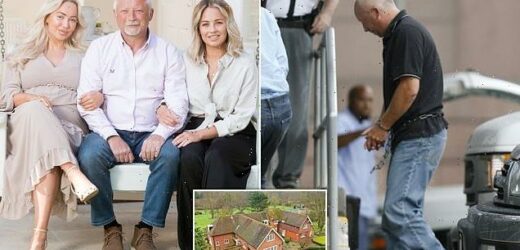

Contented: Giles now, at home with daughters Lucy, left, and Elle. During his imprisonment, he insisted his family did not visit. He couldn’t bear to think of the ordeal they would face: flying out to see him, subjected to nitpicking prison rules; bereft at leaving him after a grim and dismally short visit

After seven months in Allenwood Correctional Institution, a sprawling jail in Pennsylvania with 2,900 inmates, he was emaciated. His weight had plummeted from 11 stone to just over eight.

He recalls his brutal induction into the prison system in May 2008. ‘I was terrified; my mouth was dry, the heat was excruciating. I felt as if I’d arrived in Hell.

‘The guard snapped at me: ‘Full name!’ so loudly I recoiled. I remember thinking how out of place my West Country English accent sounded in a prison three-and-a-half thousand miles from home. My heart was racing.

‘I wasn’t prepared to be thrown straight into solitary confinement. I think it’s to keep you in line by showing you how miserable your life could be if you don’t behave.

‘The cell was 15ft by six, with a mattress so thin you could feel the bed slats. All night I could hear prisoners shouting and screaming.

‘There was a stainless steel toilet with sink attached and a desk and stool, bolted to the floor. No TV, radio or watch, so I lost track entirely of time. The small window was barred and frosted. I thought: ‘If I’m here much longer I’ll go crazy’.’

He is seen arriving at court in shackles. The U.S. energy giant Enron had collapsed in one of the biggest bankruptcy filings in history, and Giles and his two co-defendants, Gary Mulgrew and David Bermingham, were thrown into a maelstrom of media coverage

Today, tanned and neatly barbered, he looks lean, fit and relaxed. It is hard to visualise the fear and privations of those early days of his incarceration. He now lives a comfortable but unostentatious life with Lisa, 54, his wife of ten years, in a modest modern semi in his native Wiltshire. He co-owns a string of pubs and is preparing for post-Covid reopening when we meet.

Track back 20 years to the Home Counties commuter belt and we would have found him in a five-bedroom period property in the grounds of a stately home, with second wife Deborah and two of his five pretty daughters — Katie, now 23, and Elle, 25.

There were regular visits, too, from twins Sophie and Natalie, now 34, and Lucy, 30, from his first marriage to Michelle.

Weekends were spent at the family’s second home, a cottage in the New Forest; an annual bonus of £350,000 enhanced his already generous salary.

It was all a very long way from the misery he faced in prison. There, an exercise yard offered the only respite during those first days in solitary. Inmates were herded like animals into large cages, where they paced up and down. There, Giles had an early encounter with some of the colourful characters who populate the U.S. prison system.

A U.S prison is depicted above. He recalls his brutal induction into the prison system in May 2008. ‘I was terrified; my mouth was dry, the heat was excruciating. I felt as if I’d arrived in Hell’

‘An attractive Mexican girl with long, dark hair and a huge chest came into our cage,’ he recalls.

‘I assumed she was there because of some processing cock-up but she told me she’d spent the last ten months in solitary and had been transferred in the hope of getting into the general prison population.

‘I looked at her, amazed. ‘Why would they do that?’ She shrugged. ‘Well, I’m a guy.’ I was stunned.’

Subsequently, Giles heard she had been placed into the general prison population and ‘made a small fortune selling her wares most days in the unit shower block’.

Out of solitary after two days, Giles found himself in a cramped shared cell with El, a muscular black man incarcerated for 22 years for crack cocaine dealing — who became a friend and mentor — and a paunchy white middle-aged paedophile called Ross, one of the ‘lowest of the low’ in the prison hierarchy.

So how had it come to this? How had a well-educated diplomat’s son found himself in a cell with a tough street hustler whose father had been killed in a shootout?

To understand this convoluted story, we must return to June 2002 and the moment when Giles, watching the early evening TV news at home, was horrified to learn that three British bankers, himself among them, each faced 35 years in jail, having been indicted in the Enron inquiry.

‘It felt as if the air around me had been completely sucked out. I couldn’t breathe. My heart started galloping,’ he recalls.

The U.S. energy giant Enron had collapsed in one of the biggest bankruptcy filings in history, and Giles and his two co-defendants, Gary Mulgrew and David Bermingham, were thrown into a maelstrom of media coverage.

In 2006 they were extradited to the U.S., then PM Tony Blair having caved in to pressure from President George Bush.

Giles Darby’s Hertfordshire family home is pictured above before he became enmired in the Enron collapse

The photos of them arriving, shackled in chains, provoked a wave of sympathy in Britain and although all three were separately offered their freedom in return for incriminating the other two, they each refused.

The charges against them dated back to 2001, when they were investment bankers with GNW (Greenwich NatWest) merchant bank. They were accused of defrauding NatWest by selling its stake in an Enron subsidiary for $1 million to a Cayman Islands company in which they had a financial interest.

That company sold it back to Enron days later for $20 million, with Andrew Fastow, Enron’s soon-disgraced chief financial officer, sharing the profits with another Enron employer and with Darby, Mulgrew and Bermingham.

All three have consistently protested their innocence, but they agreed to the plea-bargaining deal with U.S. prosecutors in order to get a shorter sentence: had they stood trial and been found guilty, they would each have faced 35 years in jail. By pleading guilty to one count of wire fraud, they cut their sentences to just 37 months.

They maintain they did not realise they had done anything illegal; indeed, Giles points out that he was earning so much legitimately at the time, he didn’t need to augment his income by taking part in a scam.

‘At the time, we still didn’t know what Fastow had done to make so much money,’ he says, ‘but we were delighted when he paid us our share of the profits: $7.3 million between the three of us; around $2.4 million (£1.7 million) each.

‘As far as we were concerned, it was a fabulous deal. We declared the returns to the taxman and paid the full tax: that’s how sure we were that it had been above board.

‘Looking back, I was arrogant and I let hubris get in the way of my thinking. But I’d no inkling that we’d participated in a gigantic fraud.’

The ramifications for Giles were catastrophic. His financial gains had to be repaid in fines and compensation to the victims of Enron’s collapse. His second marriage to Deborah was also a casualty of the case.

Stranded in Texas, fighting to prove his innocence while his wife and children stayed in the UK, he admits he had an affair during the two years when the prospect of a long prison sentence loomed. A divorce followed.

Even so, it is to Deborah, who died last year of cancer, that he dedicates a newly published book, Inside Allenwood — fascinating, dark and sometimes grotesquely comic — about his time in prison.

During his imprisonment, he insisted his family did not visit. He couldn’t bear to think of the ordeal they would face: flying out to see him, subjected to nitpicking prison rules; bereft at leaving him after a grim and dismally short visit.

He was also too choked with emotion to speak to them on the phone and found it easier to write, pretending that prison was a picnic, inviting them to picture him ‘in a beautiful valley with picturesque scenery all around’, walking along the running track and listening to the radio.

When his daughter Elle turned 18, he did attempt to make a telephone call but, overcome with tears, found that he couldn’t even speak.

‘She was saying ‘Hello? Dad? Are you there?’ I knew if I heard any more of her voice I would have collapsed in tears in view of half the unit. I called back next day and just managed to hold it together, but it was difficult.’

In prison he got used to wearing clothes that weren’t merely second-hand but endlessly recycled: ‘Khaki trousers, white T-shirt, boxers so frayed and thin around the crotch that the fabric was practically transparent. My stomach churned when I thought about where they’d been.’

Long before Covid, he became accustomed to fist-bumping — widely favoured over handshaking (‘You never knew where the hands had been’) — and got acquainted with El, who was incredulous at the short length of his sentence.

‘Thirty-seven months? That’s chump change, man. It’s f****** nothing. It’ll be over before you even know it,’ he told Giles.

Giles explained about the plea-bargain but El, a prison veteran with high status among the other inmates, wanted to know more before he admitted the British newcomer into his coterie. Had he been a ‘rat’? Had he testified against his co-accused to get a shorter sentence? (Giles, simplifying the case, had told El he’d robbed a bank of $7 million; to his cellmate the sentence seemed extraordinarily lenient.)

Giles assured him he wasn’t a rat, which appeased El, who explained that, in the rigid prison hierarchy, ‘rats’ and sex offenders — known as ‘lollipops’ — were considered beyond the pale. He advised him to steer clear of such undesirables for the sake of his own reputation.

Soon El engineered the departure of paedophile Ross from their shared cell and another black prisoner, T, jailed for 35 years on two charges of carrying a gun and drug dealing, joined them.

For Giles, such characters were a source of fascination: during his time at Allenwood he wrote 80 letters home to his mother Pam, 83, in Sherborne, Dorset, which she then distributed to the family.

He recalls his coveted job in the prison laundry, over which a Miss Anderson, dubbed the Laundry Nazi, presided with an iron fist and a ‘real aura of misanthropy’. He earned a salary of £6.50 a month — about 20p an hour — and a glowing report card that proclaimed he’d ‘done a good job folding’.

When Shane, the laundry clerk, was ejected from his post for smuggling out items of clothing to sell on the prison black market, Giles was offered a coveted promotion.

‘The job involved overseeing all the laundry and clothing supplies for the entire prison. What a career opportunity! From a high-flying, globetrotting, fast-living banker to the custodian of all the Y-fronts in Allenwood — even I could see something deliciously ironic in that.’

Coming from a financial background, he enjoyed, too, the idea that the refectory — or chow hall, as it was known — operated a surprisingly slick black market in which food smugglers secreted milk cartons, cold burgers and scraps of scrawny chicken. Giles eschewed these extras: ‘You’ve only got to ask yourself how they were concealed from the guards to lose your appetite entirely.’

Instead, he bought teabags from the prison shop so he could sip a cuppa as he read the newspapers — usually long out of date — that his mother sent from Britain.

Although there was much that was bleakly comic, violence simmered, ready to explode at the flimsiest provocation. One evening in the chow hall, as Giles and El chatted, a metal tray clattered on the floor and a brawl began. ‘One sniff of blood brought out everyone’s inner craving for violence,’ he recalls.

Giles became an ad hoc careers adviser. The notorious Mafia mobster John Carneglia, serving 50 years for loan sharking, hijacking, murders and heroin distribution, talked earnestly about his son’s embryonic banking career.

Stories circulated that another Mafioso, in prison for several decades, had recently become a father. When Giles expressed surprise, he was told — by the laundry’s Miss Anderson, no less — that a guard had procured a squash ball and cut a slit in it: ‘Given the ball and some time alone, the Mafioso had produced what his girlfriend, waiting in the prison car park, needed. A guard rushed out with the ball and she impregnated herself with a syringe.’

During Giles’s seven months in Allenwood, his legal team were battling to get him back to Britain, where he served the remaining 11 months of his sentence in Leyhill, Gloucestershire. Actually, he missed his U.S. mates.

‘At Leyhill I was on the long-serving prisoners’ wing, surrounded by the most awful kind of people; over half were ‘lollipops’. I hated having to mix with them. In the U.S., some of the prisoners were funny, interesting; in a way I was spellbound.’

He was released in 2009 and two years later bumped into Lisa, divorced from her husband, who had been one of Giles’s old golfing friends, in a Sainsbury’s car park.

‘She popped up and said, ‘Boo!’ We went for a coffee . . . and that was ten years ago,’ he says with a smile. ‘We’re very lucky. We have a lovely life together.’

He sits at his kitchen table, the wall behind him hung with photos of his girls and nine grandchildren.

‘When I was in the City it was all about making money, chasing the next deal, survival of the fittest,’ he reflects. ‘Now life is much simpler.

‘We enjoy spending time with the grandchildren and travelling in our motorhome. We’ll have a road trip round Wales when restrictions ease.’

Having experienced the extremes of wealth and penury, it seems he has reached a middle way.

‘When you have a catastrophic life event, you cannot help but reflect on the person you were.

‘Twenty years ago I was this arrogant, money-obsessed investment banker. I was always focused on the next deal, never at home. Now I’ve become somebody I quite like.

‘I moved back to my home town [Melksham]. I spend more time with family and friends. I enjoy life. And I’m a much better person for it.’

Inside Allenwood: Money, Mobsters And Enron, by Giles Darby, is published by Quiller, £16.95.

Source: Read Full Article