What would you do if a safe-injecting room were to be located near where you lived, or worked, or where your children go to school? Even if you supported such facilities offering services to people in desperate need of help, would your view be swayed by its direct impact on your life? It’s the NIMBY (not in my backyard) conundrum writ large.

Such a vexed situation is playing out after the news that Melbourne’s second supervised drug-injecting room is to be located in an art deco building opposite Flinders Street Station, and near popular al fresco city dining laneway Degraves Street. On the face of it, locating the centre in such a high-traffic area of the CBD would seem fraught with problems.

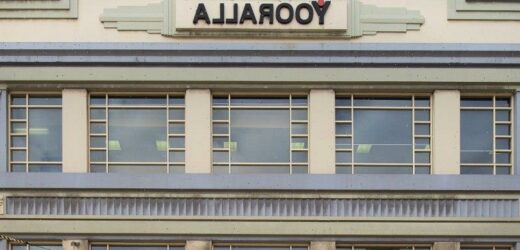

The proposed site of the new safe-injecting room at 248 Flinders Street, Melbourne.

Local businesses, which are still recovering from the protracted virus lockdowns and the disruptions from the Melbourne Metro Tunnel project, have been quick to raise concerns. The president of Residents 3000, Rafael Camillo, put it succinctly when he asserted that “if we are trying to bring back tourism and more people to live in the city, it is not the time to be building an injecting room”.

The disquiet should be taken seriously. Nearly four years after Melbourne’s first supervised injecting room was opened in Richmond, community concerns, particularly from parents of children at a nearby school, have not subsided.

That is despite the clear successes of the Richmond centre. A report on the facility, led by respected expert Professor Margaret Hamilton, found that in its first 18 months, of the nearly 4000 drug users who visited the centre a total of 119,223 times, not one person died of an overdose, despite 271 serious health incidents.

And it’s not just inside the building that lives were saved. The number of overdoses attended by ambulance officers in which naloxone, a drug commonly given to patients in those situations, was administered had dropped by 25 per cent within a kilometre of the centre.

That contrasts with Ambulance Victoria data which shows opioid-related attendances by its officers across the City of Melbourne was up 49 per cent in the five years to 2019, and had doubled in the CBD over the same period.

And, according to the State Coroner, the number of people dying of drug overdoses across Victoria has risen consistently over the past decade, with 4365 drug users dying between 2010 and 2019. With enormous pressure already on our ambulance services, this is not sustainable.

Despite the obvious shortcomings of the new proposed location, it is a known hotspot for intravenous drug users. The centre would help alleviate a problem that is largely being ignored or left to emergency services. On top of a safe environment to inject, such centres offer users a range of services, including infectious disease diagnosis and treatment, wound care, drug dependence treatment and help in finding housing and getting access to mental health services. Such aid can be life changing.

But if there is a lesson to be learnt from the Richmond centre, it’s the absolute need to consult widely to gain the support of local government, emergency services and the neighbouring community. Putting a drug-injecting room in any location requires a broader view than what goes on inside the injecting room. The ripple effect of problems that can emanate from such centres is real.

In principle, The Age supports a new safe-injecting room. Supervised centres save lives by assisting those who overdose, and thanks to the support services on hand. But the backlash from the local community must also be listened to. The NIMBY effect may be alive and well, but when it reflects genuine concerns then it cannot be disregarded.

Note from the Editor

The Age’s editor Gay Alcorn writes an exclusive newsletter for subscribers on the week’s most important stories and issues. Sign up here to receive it every Friday.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article