If Keith Banks peers back into the darkness, his mouth is flooded with the gun-oil taste of the service pistol he placed in his mouth to end it all.

Sitting in his favourite chair with a bellyful of Scotch and a mind full of trauma, he knew he was less than 500 grams of trigger pressure away from joining the mate he had seen die on a raid for one of Australia’s most dangerous criminals.

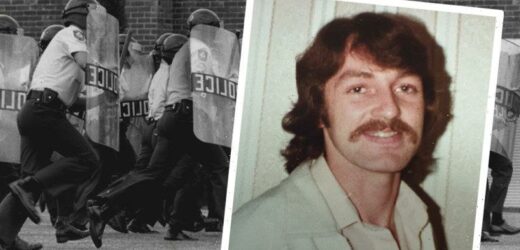

Keith Banks: Battle from the brink.

“I don’t remember cocking the slide to chamber a round, but I found myself looking at the pistol in my hand with the hammer back and the safety off. I remember thinking I could make all the pain go away quickly.”

Keith is a former policeman, a hero and a victim. He is a man who stared into the abyss and then stepped back.

His book Gun to The Head should be on the reading list of every police leadership and management course in Australia.

It is the story of an idealistic kid who joined the Queensland Police to keep the peace and ended up going to work hoping to kill. It also exposes how petty police politics, penny-pinching programs and wooden-headed management contributed to the death of a fellow officer.

“I defy anyone to walk in the shoes of police in the real world and walk away unaffected. Post-traumatic stress disorder is not only caused by extreme events of life-threatening danger, but it also accumulates over years of dealing with darkness and evil people,” he writes.

Queensland’s undercover police in firearms training.

Banks had been in the first generation of undercover cops in Queensland, who made the rules up as they went along, were allowed to smoke dope on duty and learned quickly not to trust a corrupt cell of detectives who would sell them out for the price of a cheap suit.

He loved it but the trouble was when he returned to daily policing he missed seat-of-the-pants undercover work. “I needed to find that addictive rush of adrenaline again. Fear and exhilaration are blood brothers; that’s what drives risk. I should have been careful what I wished for.”

In 1982 Queensland’s Emergency Squad consisted of 50 full-time police who trained part-time to respond to sieges, terror attacks and armed offenders.

It was the sort of gung-ho work that suited alpha-cops like Banks. Soon he found a kindred spirit in Peter Kidd. Both understood the squad would soon follow Victoria’s Special Operations Group to become a full-time strike force and they wanted to get in on the ground floor.

Peter Kidd.

At their first training session Kidd said he would apply for a full-time position and Keith responded: “Mate, I’ll be right behind you.” They shook hands on their private pact.

In 1984 the squad, now called the Tactical Response Group, went full-time, with Kidd and Banks first through the door – as they would be in the many raids that followed.

Banks was in his element but soon learned the greatest risk came from superior officers with inferiority complexes. The squad was assigned to protect “Rocky”, a mafia cannabis cropsitter turned star witness in a murder trial.

Banks liked Rocky and turned a blind eye when he smoked dope: “For a crook he was a lovely little guy.” Rocky gave evidence at the committal hearing “like a pro”, then an assistant commissioner stepped in to downgrade security to save money.

Rocky, now knowing he was expendable, rang his mother, who told him the mafia had reached out to say if he didn’t give evidence he would be safe.

Banks knew it was a horrible mistake but couldn’t change Rocky’s mind. The last time he saw him was at the bus station outside police headquarters: “We shook hands and said our goodbyes.”

A few months later the mafia men who promised Rocky a free pass flew him to Italy for a holiday. His body was found with two shots to the back of the head.

In July 1987 the squad was assigned to arrest Paul Mullin, Queensland’s most wanted and dangerous man. Mullin had escaped from Sydney’s Long Bay Prison in 1977 and survived, largely by robbing banks.

Finally, there was a tip-off that he was living in house in the Brisbane suburb of Virginia.

Banks and his team looked at the options, deciding on a forced entry raid through the rear of the house. Mullin was heavily armed and prepared to shoot, and there were three potential hostages – including two children – in the house.

The scene of the July 1987 raid in the Brisbane suburb of Virginia that would end in the death of Queensland’s most wanted man, Paul Mullin, and undercover police officer Peter Kidd.

Banks knew speed and surprise was their best hope, which is why he planned to use tear gas and distraction grenades to grab Mullin before he could grab the kids as hostages.

But when presented to senior police, the operation was approved without the use of the gas and stun grenades. The modifications were made despite police knowing Mullin’s firearms were more powerful than theirs.

There was another curious demand. Usually, the police who plan and conduct the raid are given control of its timing. Yet for this operation Banks was given no option. The raid had to be carried out the next day.

That week in July the Fitzgerald inquiry – which exposed corruption and led to the jailing of the reptilian Queensland Police commissioner Terry Lewis – was holding its first public hearings.

Qld Police Commissioner Terry Lewis. As rotten as a chop.Credit:Fairfax

Banks believes that while he was denied distraction grenades, the raid’s timing was designed to be a distraction from negative headlines.

What better way to get Fitzgerald off page one than to kick down a door and grab Queensland’s most wanted? It worked, but in the worst way imaginable.

Banks picked two teams. Peter Kidd was not selected in the initial group but after one officer had to pull out, Banks agreed that Kidd would be the first through the door. “I made the decision that would haunt me for the next 25 years,” Banks writes.

They wore protective vests they knew couldn’t stop a bullet from Mullin’s military-grade Ruger semi-automatic .223 rifle. Kidd had written a detailed report recommending an upgrade in ballistic vests. It was knocked back on budgetary grounds.

When they burst in, Kidd opened the main bedroom door to find a naked and armed Mullin ready to fire. Kidd and another officer were shot before Mullin was killed by Banks and the team when they returned fire.

Banks went to Kidd and tore off his vest to see four entry wounds. He could only hold his hand and try to comfort his dying mate. “There was nothing I could do.”

He threw himself back into his work, hiding his anguish by drinking to blackout, waking then returning to duty. “There was no doubt I was a changed man, and not in a positive way … I was crippled with guilt at having let Pete take part in the raid.”

Keith Banks (right, looking at camera) with other undercover police at a training facility.

The naturally calm Banks became quick to anger and made himself a promise. “I was never going to give someone the chance to drop their gun.” If they even looked like pointing it at anyone, they were dead.

Banks now knows that during those dark days he volunteered for the dangerous jobs, hoping he would find himself in a fatal confrontation. He began to smoke dope again, crying in private while presenting publicly as the armed expert ready for anything.

Two years after seeing his mate shot dead, Banks left the Tactical Response Group, but he wasn’t finished with armed offenders.

Six years after shooting Mullin, Banks walked into Brisbane’s MLC building to deal with a man armed with a rifle, hand grenade, 16 sticks of gelignite and three detonators. The policeman who had wanted to kill spent 90 minutes persuading the man to surrender.

Banks was presented with two Valour Awards, for the Mullin raid and the MLC building siege.

Keith Banks receives two Valour Awards on one day.

For Banks it was time to leave policing. He was recruited by ex-Victorian armed robbery squad detective Mark Wylie, who had become a Myer executive.

Wylie and Banks had much in common. Both had troubled childhoods and became idealistic cops only to be traumatised by shootings.

Wylie was shot while leading a raid for one of the 1986 Russell Street bombing suspects. Because of a shortage he was not wearing a vest when shot. In 2014 he took his own life.

For Banks, writing Gun to the Head has been a difficult and cathartic experience. He is finished with policing but policing isn’t finished with him.

Gun to the Head by Keith Banks … required reading for those who manage police.

Mentally he is in a better space but PTSD is not an illness that passes over time. It retreats into a dark hole to emerge when it sees an opportunity.

For Banks it takes the form of a recurring nightmare. He is armed and sees the offender. “I aim at my enemy and squeeze the trigger, but it is locked in place … The gun is useless and I am defenceless … My mind drifts back all those years and there’s no more sleep for me.

“The dreams are fewer these days but come unbidden, just like the waves of sadness that ebb and flow without cause or remedy.

“Such is the dark legacy of PTSD.”

Gun to the Head by Keith Banks is published by Allen & Unwin.

For help or information call Suicide Helpline Victoria on 1300 651 251 or Lifeline on 131 114, or visit beyondblue.org.au

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article