BEIJING — Countless hours of extra laps and self-induced pressure led Kristen Santos to the Utah Olympic Oval on Dec. 18, 2021, four years and one day after heartbreak.

She’d been “working forever” to become an Olympian. In December of 2017, she'd fallen a split second short. So, day after day, month after month, she pushed, through pain, into her mid-late 20s, back to U.S. short track speedskating trials to realize a childhood dream. With friends and family roaring in December, she sped to victory, and burst with emotions she couldn’t explain. A tear rolled down her cheek. A smile broke through exhaustion. She’d made it to the 2022 Olympics. Or, rather, she almost had.

First, she had to evade COVID-19.

And so, the 27-year-old from Fairfield, Conn., spent the next five weeks “doing absolutely nothing besides training.” Even her fiancé went into "a complete lockdown.” He visited his office at 10 p.m. to circumvent human contact. She double-masked while picking up meals at drive-throughs, and “even then,” she said, she was “scared I'm gonna get COVID.” And she wasn’t alone.

Throughout January, athletes from dozens of Omicron-infested countries took part in this same high-stakes Olympic event: Virus avoidance. Many of them qualified throughout December and January. As they did, they quickly realized that COVID, which was exploding past previous peaks, was the one unseen barrier between them and the Games. The one thing that could undo decades of dedication and monotonous training. The one injury that couldn’t be overcome.

So they spent the most exciting weeks of their lives in borderline isolation, dreading grocery stores and breakfast buffets, holing up in rented condos, preparing for their actual Olympic events but also stressing about this one.

“The next two weeks for me,” U.S. luger Emily Sweeney said in mid-January, “are just about trying to find consistency, while maintaining my speed and not getting COVID.”

“Everyone is testing positive right now,” she continued. “And that freaks me out.”

Going to extreme measures to avoid COVID

Sweeney and her USA Luge teammates spent much of the buildup to the Games in Europe, trekking from hotel to track, to hotel, to track, supporting one another but also distancing from one another as much as they could.

Sweeney would think about “all the crappy situations” she’d endured to reach a second Olympics. The broken neck and back. The fear they provoked. The depression. The ups and downs of life as a soldier-athlete in an unglamorous sport. She’d cleared untold hurdles, and had “that second bid in my grasp.” Yet she was uneasy, because around every corner, it seemed, COVID would appear. Family members had it. Friends had it. Fellow athletes had it.

"I'm alarmingly aware of it,” Sweeney said. “It just feels like such a big risk to just be existing in this world right now.”

After qualifying, two of her teammates, Sean Hollander and Zack DiGregorio, returned to Utah with a coach and teammate-turned-mentor. In part to mitigate risk, they created what DiGregorio called a “little four-man bubble.” They fired up Instacart and Uber Eats for food.

Back in Switzerland, Summer Britcher, another luger, sometimes felt that food wasn’t worth the risk. “We had a buffet,” she explained. "[If] it was a little too crowded, I said, ‘Well, I guess I'm not eating this meal.’ And just walked right back out.”

Across the U.S., Olympians in every sport developed tactics that became as regimented as training sessions. Corinne Stoddard, a 20-year-old speedskater, would go to practice, then home, “then I walk my dog, and I do that on repeat every day,” she said.

Nathan Chen, a star figure skater, has been wearing masks during practice, and two while giving interviews afterward in Beijing. “Just better safe than sorry, I suppose,” he said.

Kaitlin Hawayek and Jean-Luc Baker, a figure skating pair, celebrated their first Olympic berth with a hallway hug, but not with parents or friends. “We FaceTimed our families,” Hawayek said. After the skate that earned them a trip to Beijing, they “went straight from our podiums back to our hotel rooms.”

But still, for many Olympians, the virus loomed. Despite precautions, every nasal swab brought anxiety. Every face-to-face meeting stirred stress. “You just punched your ticket to the Olympic team,” luger Chris Mazdzer explained, but “you're still not there. Because you have to make sure you continue to test negative. And there's really no way to make the risk go down to zero.”

“We're all vaccinated, we're all safe, we wear our masks, sanitize, every hour,” luger Tucker West said. “But you can only do so much. You never know when you're going to catch it or if you're going to catch it."

What happens when Olympians test positive

Elana Meyers Taylor felt she’d done everything in her power to win this first Olympic event. She hunkered down in Europe with her husband and breastfeeding son. She arrived in Beijing last Thursday, tested negative at the airport, and readied herself to win a fourth Olympic bobsled medal.

Two days later, she tested positive. And a journey that had outlasted pregnancy, and a trip to the neonatal intensive care unit, and the challenges of motherhood during a pandemic, suddenly veered off course.

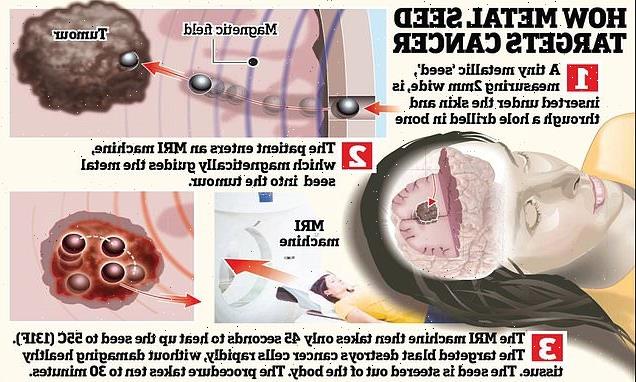

Meyers Taylor is boosted and asymptomatic. Beijing Olympic protocols, however, require her to isolate for at least 10 days. Only three consecutive PCR tests that reveal a sufficiently low viral load (CT value ≥ 35) will clear her to return to training and competition. Until then, she’s stuck living out the nightmare that hundreds of athletes feared.

Very few of them worried about getting sick. “I’m not concerned for my health at all,” one snowboarder said. They were, instead, afraid of strict protocols that, as Vanderbilt infectious disease specialist Bill Schaffner warned, could “disqualify some people for no good reason.”

Those protocols currently have Josh Williamson, a U.S. bobsledder, stuck in Los Angeles, as the lone Team USA athlete who hasn’t yet traveled to Beijing. Williamson tested positive for COVID on Jan. 23. He said Tuesday that he has begun testing negative. But he’s still “unsure of when I can fly” to Beijing, he said. Amended protocols finalized last month suggest that he’ll need four consecutive days of negative tests, plus a fifth-day buffer, before he can depart.

The rules have already deflated Olympic dreams for some non-U.S. athletes. Others now find themselves in a race against the clock. Sixty-seven athletes and team officials have tested positive for COVID at Beijing Capital Airport or inside the Olympic bubble since it opened. As Friday’s Opening Ceremony approaches, many remain confined to isolation in hotel rooms. Like Meyers Taylor, all they can do is sit, wait and hope.

They'll also train. They’ll reinvent quarantine workouts. Meyers Taylor — in between FaceTime sessions with her son, who is staying with her father in a separate room; and after pumping breastmilk to feed him — has been lifting and working to have more exercise equipment delivered to her room. She wants to stay ready, if she tests out of isolation prior to her first competition on Feb. 13.

But she knows the virus operates on its own timeline. She knows there’s nothing she can do to accelerate it. Her Olympic participation, somehow, after all she conquered to reach Beijing, is now completely out of her hands.

“We outran COVID as long as we could,” she said in a text message from her isolation room in Beijing. “And it finally caught us.”

Jeff Eisenberg contributed reporting.

Source: Read Full Article