The invasion of the Brazilian Congress, Supreme Court and Planalto Palace by backers of ex-president Jair Bolsonaro seeking to emulate the storming of the US Capitol is the culmination of a democratic downhill slope worldwide and not the people’s revolution it purports to be.

The parallels with the far-right movement ignited by former US president Donald Trump are many.

Just like Trump, Bolsonaro planted the seeds of distrust in the country’s democratic institutions – the Supreme Court included. Just like Trump, he claimed the election could be stolen and repeatedly made false claims about voting fraud during his re-election campaign. Like Trump, he didn’t concede defeat and refused to attend the inauguration of his replacement. Like Trump, he ran to Florida to nurse his bruised ego.

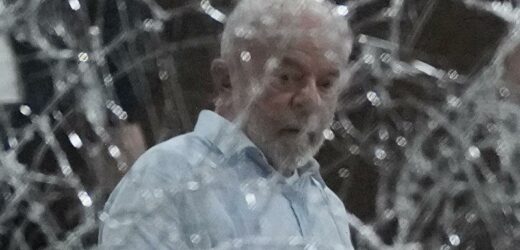

Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva inspects the damange at the Planalto Palace after it was stormed by supporters of his predecessor Jair Bolsonaro in Brasilia on January 8.Credit:AP

What is less well known, is that, like Trump, the Bolsonaro clan – three of his sons are elected MPs or senators – has had advice from and has much in common with Steve Bannon, the controversial ex-Trump White House chief strategist whose mission in life is to upend the political establishment.

As Felipe Mortara, a former veteran political journalist in Brazil, told me, Bannon and his meme-driven expressions of patriotism are extremely seductive to a large section of the population. They latch onto lies about a stolen election to justify radical responses. (Bannon himself in November posted a video saying there were no better people in the world but the Bolsonaros and claimed that all people in Brazil were fed up. “It’s going to be very interesting to see how that plays out. Use this as a warning,” he said.)

Protesters, supporters of Brazil’s former president Jair Bolsonaro, broke through police barricades to storm the Planalto Palace in Brasilia.Credit:AP

The choice of Sunday for the riot, Mortara believes is also a nod to a strategy of maximum impact, he says. A day of no political competition, maximum media exposure through end-of-week popular Sunday night news programs and when most people are off work and free to travel and to foment social media.

Just like followers of Trump, supporters are clad in the country’s flag and colours, purportedly to embody the power of the people against the corrupt establishment and to speak for the oppressed. In most cases, they were radicalised via social media where posts capitalise on real discontent to create urgency, chaos and more division.

Brazilian congressman Eduardo Bolsonaro, left, meets with former Trump chief strategist Steve Bannon in New York in the lead up to his father’s presidential election win in 2018. Credit:Twitter/@BolsonaroSP

The movement has been prominent too in France and Germany, among others.

A worrisome difference, however, are the demands by Bolsonaro supporters for military intervention – a return to the dark days of the dictatorship when hundreds of activists were disappeared, outspoken artists sought political asylum overseas and generals grew rich from corruption. They argue that in those days the country was run orderly.

Bolsonaro supporters stand on the roof of the National Congress building in Brasilia after storming it.Credit:AP

Nicole McLean, who heads a Brazilian politics discussion group at The University of Melbourne, said the rioting in Brazil did not come as a surprise.

“I was kind of expecting it. We know that Brazil takes their culture, society and political influence cues from the US.

“A few differences though, I have not seen Bolsonaro calling for people to act himself, and I find the focus on the STF [the Supreme Court] interesting.

“My interpretation is Bolsonaristas are acting out revenge on the STF and [Minister Alexandre] Moraes [who] was very critical of Bolsonaro.”

McLean, who is a doctor of social political sciences and specialist in political movements in Brazil, said the process of polarisation dates back to 2013, when members of the middle class began to engage in protests and counter-protests that culminated with the impeachment of then president Dilma Rousseff. Then, the right tried to paint itself as democratic, non-violent and non-corrupt, and the left as driven by violent radicals.

“That has completely flipped,” she says of the violence adopted by the far-right now.

“What is similar to the US, is that we have a president in Bolsonaro who was not professional in any way, and who instigated outrage against the Supreme Court and democratic institutions, which fractures the whole political structure. Having a populist leader who pushes these extreme views onto the population just feeds dissent.

“Like [what] happened in the US, people get consumed by this extremism.”

So-called Bolsonaristas continue to call for more protests, as well as the invasion of broadcasters Globo and Bandeirantes, which they say are not reporting the events “properly”.

They want the riots to be seen as democracy at its best. History is likely to record it as a large section of the population – those on the ground and those justifying their actions – displaying it at its worst.

Get a note direct from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article