LONDON (Reuters) – British interior minister Priti Patel on Friday approved the extradition of WikiLeaks’ founder Julian Assange to the United States to face criminal charges, bringing his long-running legal saga closer to a conclusion.

Assange is wanted by U.S. authorities on 18 counts, including a spying charge, relating to WikiLeaks’ release of vast troves of confidential U.S. military records and diplomatic cables which Washington said had put lives in danger.

His supporters say he is an anti-establishment hero who has been victimised because he exposed U.S. wrongdoing in conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq, and that his prosecution is a politically motivated assault on journalism and free speech.

The Home Office said his extradition had now been approved but he could still appeal the decision. WikiLeaks said he would.

“In this case, the UK courts have not found that it would be oppressive, unjust or an abuse of process to extradite Mr Assange,” the Home Office said in a statement.

“Nor have they found that extradition would be incompatible with his human rights, including his right to a fair trial and to freedom of expression, and that whilst in the U.S. he will be treated appropriately, including in relation to his health.”

Originally, a British judge ruled that Assange should not be deported, saying his mental health problems meant he would be at risk of suicide if convicted and held in a maximum security prison.

But this was overturned on an appeal after the United States gave a package of assurances, including a pledge he could be transferred to Australia to serve any sentence.

Patel’s decision does not mean the end of Australian-born Assange’s legal fight which has been going on for more than a decade and could continue for many more months.

He can launch an appeal at London’s High Court which must give its approval for a challenge to proceed. He can ultimately seek to take his case to the United Kingdom Supreme Court. But if an appeal is refused, Assange must be extradited within 28 days.

“This is a dark day for press freedom and for British democracy,” Assange’s wife Stella said. “The path to Julian’s freedom is long and tortuous. Today is not the end of the fight. It is only the beginning of a new legal battle.”

WikiLeaks first came to prominence when it published a U.S. military video in 2010 showing a 2007 attack by Apache helicopters in Baghdad that killed a dozen people, including two Reuters news staff.

It then released hundreds of thousands of secret classified files and diplomatic cables in what was the largest security breach of its kind in U.S. military history.

U.S. prosecutors and Western security officials regard Assange as a reckless and dangerous enemy of the state whose actions imperilled the lives of agents named in the leaked material.

He and his supporters argue that he is being punished for embarrassing those in power.

“Allowing Julian Assange to be extradited to the U.S. would put him at great risk and sends a chilling message to journalists the world over,” said Agnes Callamard, Amnesty International’s secretary general.

The legal saga began at the end of 2010 when Sweden sought Assange’s extradition from Britain over allegations of sex crimes. When he lost that case in 2012, he fled to the Ecuadorean embassy in London, where he spent seven years.

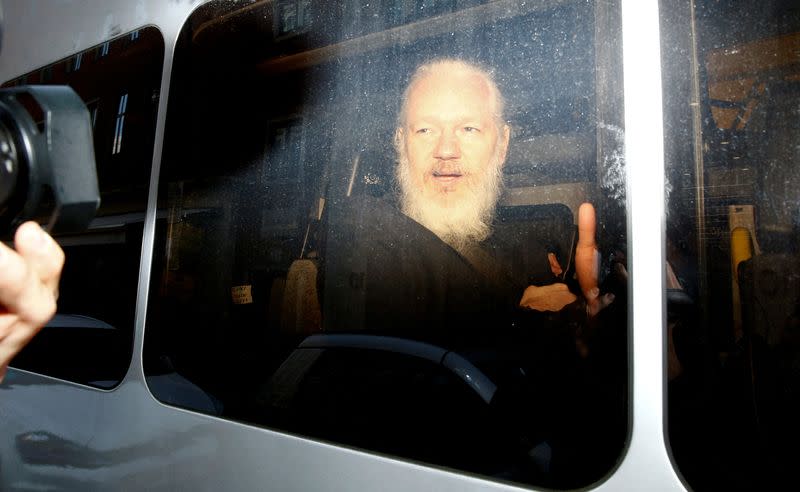

When he was finally dragged out in April 2019, he was jailed for breaching British bail conditions although the Swedish case against him had been dropped. He has been fighting extradition to the United States since June 2019 and remains in jail.

During his time in the Ecuadorian embassy he fathered two children with his now wife, who he married in Belmarsh high-security prison in east London in March at a small ceremony attended by just four guests, two official witnesses and two guards.

Source: Read Full Article