As Victorians look to move on from the past two years that have seen their lives disrupted by a pandemic that no one wanted, the Victorian government has delivered a budget firmly focused on mopping up the lingering impacts. But does it give the economy the space to continue its recovery, or is it delaying an inevitable fiscal reckoning?

Protecting our health system from collapse was the primary focus during the pandemic across Australia, however rising demand and sick patients are placing unsustainable pressure on health services. The federal government did little to help this growing pressure just over a month ago, failing to fund the implementation of its own 10-year primary healthcare plan which would take pressure off growing demand for hospital services.

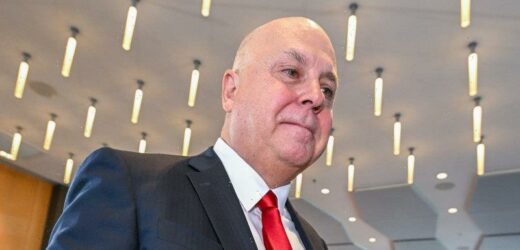

Victorian treasurer Tim Pallas delivers his budget speech.Credit:Joe Armao

The Victorian government is investing $12 billion over four years to shore up an ailing health system, but the risk remains that without fundamental reform and investment in prevention the costs will keep rising. To that end the Victorian government has provided some additional funds for community healthcare and the expansion of hospital-in-the-home programs, which will make our health system more efficient and sustainable. However, the investments remain a fraction of the cost of hospital services, with just $1 in every $20 of health spending going towards services that keep us healthy and out of hospital.

The COVID-19 pandemic unleashed a wave of inflation across the world, with the cost of living now firmly top of mind for households. Victorians on low and fixed incomes are being hardest hit as they have little capacity to absorb rising food, housing and energy costs. Alleviating cost-of-living pressures without adding further to inflation is a tight balancing act for governments to traverse. To this end the $250 Power Saving Bonus for all Victorian households is modest when compared to the federal budget in April, however it could have been more tightly targeted at households facing the greatest hardship.

A bigger cost-of-living issue that will only intensify in the months ahead however is the real wages cut facing Victoria’s biggest workforce, its public servants. Victorian public servants are subjected to a 1.5 per cent wages cap policy, and many are locked into long-term agreements. Popular with governments of all levels across Australia, these wages cap policies have acted to undermine wages growth across the economy.

With inflation running at 5.1 per cent, the Victorian policy has already delivered large cuts in real wages for public servants with the prospect of more pain ahead. This is unlikely to be sustainable, especially if inflation remains elevated and any moves to lift public sector wages will add to government spending and debt.

Debt is the longest tail that the pandemic is likely to leave Victorian taxpayers, with interest payments forecast to be 6 per cent of all spending over the next four years. While Victoria’s debt burden was growing before the pandemic hit, it has more than doubled in the past two years and is forecast to triple by 2025-26.

The government is proposing a new future fund to manage the cost of this debt into the future. The fund will invest $10 billion of taxpayers’ money for commercial returns, rather than paying down debt. The idea is that the government can earn more from these investments than it would save from lowering its debt. The NSW government made a similar commitment last year, and while modest in terms of the whole of the government’s balance sheet, represents a higher risk to taxpayers and should not be seen as an alternative to responsible fiscal management.

Victorians that remember the debt crisis of the early 1990s might be worried about whether debt levels are sustainable, and whether it will ultimately lead to a need for large cuts in services or an increase in their taxes. But we should remember that things are very different from the early 1990s, with low interest rates on the Victorian government debt that are largely locked in for the next 10 years. The economy is also much healthier with strong employment and economic growth, and this is ultimately the key to managing and paying down the debt.

Cutting services or lifting taxes today to get the budget back into black would be counterproductive, undermining economic growth and the living standards of Victorians. At the same time there is a need for a path back to sustainable spending and growth in debt, and while the Victorian budget provides that path it is premised on a number of assumptions.

Ultimately the budget will be judged on whether the Victorian government’s additional investments can address the worst impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, and whether the assumptions of a continuing economic recovery hold. While this budget does its best to support a strong recovery through continuing investments in infrastructure and social services, if the past two years have taught us anything, then events outside a government’s control can change things overnight.

The Victorian government will be hoping that there are no such nights between now and the state election in November.

Dr Angela Jackson is lead economist at Impact Economics and Policy. She was deputy chief of staff to former federal finance minister Lindsay Tanner.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article