I’m a Pacific Islander, but I still struggle to call myself AAPI or APIA. I’m not Asian American; at least I’ve never considered myself to be. But over the past few months, my social media feeds have been filled with calls to “Support AAPI” or “Stop AAPI Hate,” once again reminding me that in the eyes of so many, being Pacific Islander is simply part of a larger whole. There’s power in a name, and I can’t help but wonder if the people posting these hashtags understand the vast community they’re addressing.

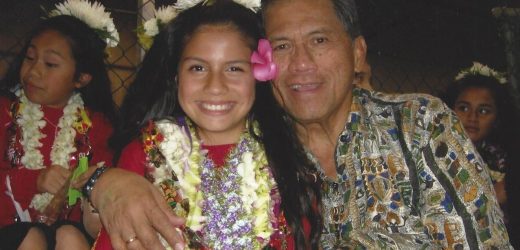

The national focus on APIA recently caused me to reflect on my own identity. I’m second-generation Hapa, born to a half-Hawaiian mother and a father with Samoan and Maori roots. My parents, both raised on the mainland, prioritized my family’s connection to our ancient heritage. I learned to hula dance around the same time I started walking. The car radio on long drives with my grandparents always played a mix of Keali’i Reichel and ancient chants. Someone broke out a ukulele at every first birthday party or wedding.

My story is just one in the wide APIA net. As a group, Asian Pacific Islander Americans contain multitudes: East Asians, South Asians, Polynesians, Micronesians, Melanesians. We come from wildly different regions and distinct cultural backgrounds. How did we get grouped together in the first place? And will we always remain this way? To answer these questions, I chatted with the University of Washington’s American Ethics Studies chair, professor Rick Bonus.

Bonus is the author behind The Ocean in the School: Pacific Islander Students Transforming Their University, and has spent years working with Pacific Islander students. He told me that it’s hard to trace back exactly where the APIA grouping started (unfortunately, the research just isn’t there yet) but we can look to the census as a starting point. This echoes the experience my own mom had growing up, where she could self-identify as “Asian” on demographic reports. It wasn’t until years later that a box for Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders appeared, finally acknowledging a separation between the groups.

As Bonus reminded me, this kind of grouping isn’t only unique to APIA — “it’s also true with other major racial groups.” Lumping different heterogenous populations can actually be powerful because “there’s a lot of mobilization of common interests, common histories, common advocacies.” But there’s also much at stake. “You risk marginalizing certain groups that are not as powerful or as hegemonic as the more vocal groups in that category. That’s what’s happening to AAPI.”

Society appears to assume that Asians and Pacific Islanders are all similar people, but data collection suggests differently. Our access to education, healthcare, and employment varies. Pacific Islanders only make up about 0.4 percent of the US population, and can easily get overshadowed or ignored. “We know that, within the group, there are more powerful, more vocal, more aggressive larger groups than others,” Bonus said. There can be further marginalization within already marginalized communities.

Bonus sees this frustration in his students, who come to him feeling devalued, alienated, isolated, and even invisible. “You get this feeling that nobody knows your people’s history, or even if they know, it’s such a gross misunderstanding,” he explained. But there’s power in finding others who are living similar experiences, who are looking for kinship and want to celebrate your culture in the same way. Bonus recommends that Pacific Islander youth who feel alone should turn to their educators, city libraries, and community centers for direction in finding more people like themselves. Cling to the collective culture we’re raised in, where everyone is a cousin, auntie, or uncle.

We can also learn a lesson from Bonus’s students. “A key to their advocacy was being together, loving each other, caring for each other, and being in the struggle together. That addressed a whole lot of anxieties about being isolated, feeling alienated because they felt the same way. They were in the struggle together and they were in the advocacy together, and that’s key to dealing with all these issues.” As I’ve grappled with my own sense of self, I find myself increasingly craving that same community support.

My own feelings of “otherness” are also lessened when I see Pacific Islanders start to get more visibility than perhaps ever before. We’re stepping into political positions, getting media airtime, hell, Disney is making movies about Polynesian princesses. But as Bonus described, we should seek more than just representation — we should seek recognition. We must avoid “decorative diversity” and understand that the quality of our presence counts. Our labels will evolve and change, and who knows what the future will bring? Whatever that future looks like, we’re allowed to question, to criticize, to push back, to claim our space, and demand that our voices be heard.

I wish I could say my conversation with Bonus fully alleviated by cultural anxiety, but alas, I’m only human. This is a generational struggle that I will continue to unpack as the world emerges from a pandemic and the years go by. I will someday raise children of my own who will likely face similar identity crises. But I am reminded that I feel stronger with my community by my side. I’m joining a hālau in my new neighborhood. I’m dusting off traditional music I haven’t listened to since childhood. I’m researching my geneology in hopes of getting closer to my heritage. I’m embracing who I am with less concern if the world will do the same. May other Pacific Islanders find a similar path forward, and may we eventually receive the recognition we deserve.

Source: Read Full Article