The world’s nuclear arsenal had started to seem irrelevant – until Putin put his nation’s on high alert. What is the likelihood of him using nukes and where does this leave “deterrence” today?

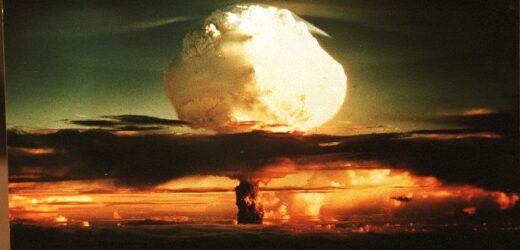

On July 16, 1945, just before dawn, the age of nuclear terror began. A fireball brighter than the sun lit up the New Mexico desert. The watching scientists cheered and shook hands. This was the world’s first test of a nuclear weapon, and, contrary to fears that it could ignite an unstoppable chain reaction setting the whole world on fire, it had worked.

And yet, exactly what that meant was sinking in too. The lead scientist of America’s secretive Manhattan Project to build the bomb, Robert Oppenheimer, said that words of Hindu scripture ran through his mind as he watched the mushroom cloud over the explosion: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Less than a month later, the United States dropped two nuclear bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to force the country’s surrender and end World War II, killing hundreds of thousands of people. It remains the only use of nuclear weapons in war.

Soviet espionage soon unlocked the secrets of that bomb, beginning a nuclear arms race that would spiral into the Cold War. But mutually assured destruction has long kept weapons locked away. Now, in invading Ukraine, Russian President Vladimir Putin has conjured the spectre of nuclear war for the first time in decades, threatening the West with extraordinary consequences if they interfere, and taking the rare step of putting Russia’s nuclear defences on alert. Though neither side wants nuclear war, analysts warn Russia may yet consider using smaller, localised nuclear weapons to beat Ukraine into submission. Even a nuclear bluff could rapidly spiral out of control, as could conventional attacks on Ukraine’s nuclear power plants.

Addressing Australia’s parliament from Kyiv on March 31, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky warned that Russia’s “nuclear blackmail” now loomed over all countries, the fears of the previous century reawakened. “What is happening in our region has become a real threat to your country and your people as well,” he said.

So, are nuclear weapons likely to come into play? How would the West respond? And does nuclear deterrence still work today?

The first test of a hydrogen bomb using nuclear fusion by the US during the Cold War in 1952.Credit:Getty Images

What are nuclear weapons and who has them?

To understand the world’s most powerful weapon you have to start on a very small scale. Atoms are the building blocks of matter, and the nucleus of each is held together by a powerful force. In 1938, the race to harness this energy in an atomic bomb kicked off when two scientists accidentally split apart uranium atoms in Nazi Germany. Fears that the Nazis would be first to develop such a weapon inspired big investment by both the US and the UK (and interest from their then-ally the Soviet Union).

The atomic bombs that the US unleashed in World War II work through a chain reaction known as nuclear fission – by splitting the atom of isotopes such as uranium and plutonium. During the Cold War, America and Russia made hydrogen bombs thousands of times more powerful than those dropped on Japan using a process known as nuclear fusion which works in reverse – binding together nuclei – in the same way the sun produces energy. (Oppenheimer’s opposition to the development of more powerful bombs later cost him his job.) Modern nuclear bombs use both fission and fusion.

Today nine countries have nuclear weapons – the US, Russia, China, France, the UK, Israel, India, Pakistan, and North Korea – but the US and Russia hold 90 per cent of the world’s nuclear arsenal. (That’s estimated at 6000 nukes for Russia and more than 5000 for the US compared to a couple of hundred held by China, France and the UK, and only a few dozen for North Korea.)

Treaties designed to disarm and stop the spread of nuclear weapons (such as the Non-Proliferation Treaty) mean the world’s arsenal has shrunk significantly since the end of the Cold War, down from a peak of about 70,000 weapons in 1986 to an estimated 12,700 today, according to the American Federation of Scientists, although this is often due to the retirement of older missiles. Countries such as Libya and Iran, which have attempted to create their own nuclear weapons since (or, in the case of Iraq, were thought to be trying), have often faced harsh sanctions and even war from the US and its NATO allies.

Under the logic of “nuclear deterrence”, the fact the great powers hold nuclear weapons is said to make major wars less likely. But groups pushing for disarmament and not just non-proliferation of nukes warn that some countries, including China, are again increasing their nuclear arsenals, and the risk of a catastrophic nuclear war remains so long as nuclear weapons do. “The warheads on just one US nuclear-armed submarine have seven times the destructive power of all the bombs dropped during World War II, including the two atomic bombs,” says the Union of Concerned Scientists. “And the United States usually has 10 of those submarines at sea.”

The major nuclear powers have long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles (IBMs) designed to carry these warheads thousands of kilometres in minutes, as well as anti-missile defence systems to detect and shoot them down. In March, with the world’s eyes on Ukraine, North Korea broke its moratorium on testing IBMs and fired its most powerful missile yet, although the trial may not have been as big a success as it claimed.

Nuclear arsenals have evolved to include less powerful or “low-yield” nukes too (sometimes called tactical or non-strategic nuclear weapons) – and experts say this carries its own risks. If the effect of a nuclear strike can be contained to a more localised area, and the radioactive fallout reduced, will that make countries more willing to break the “nuclear taboo”, the “do not fire first” principle that stopped the Cold War spiralling into nuclear armageddon?

In 2017, Russian President Vladimir Putin said the US was housing nuclear weapons too close to Russia, as both sides accused the other of violating the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.Credit:Sputnik Kremlin

Could nuclear weapons come into play in Ukraine?

Ukraine gave up its nuclear weapons after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 in exchange for a guarantee that Russia would not interfere in its sovereignty. That means this war is not between two nuclear powers (as conventional clashes between India and Pakistan have been, for example). And peace negotiations could yet stop it.

But if Putin turns to a weapon of mass destruction to break through strong Ukrainian resistance, such as a chemical (poison) or a tactical nuke, he will be crossing a line that could drag him into conflict with nuclear powers in the NATO alliance, particularly the US.

As well as putting its nuclear forces on high alert for the first time since the Cold War, Russia reports its nuclear submarines are running drills and mobile nuclear missile launchers are roaming the forests of Siberia to practise secret deployments.

“The prospect of nuclear war is now back within the realm of possibility,” warned United Nations secretary-general Antonio Guterres on March 14.

Retired Major-General Mick Ryan, formerly of Australia’s Defence Force, thinks it more likely Russia will unleash chemical weapons in Ukraine, “but [the nuclear threat] is not zero”.

Experts say this is the world’s most dangerous nuclear moment since the Cold War. “But the old Cold War had safeguards” for most of it, says Dr Bobo Lo, a former Australian diplomat to Moscow. “It wasn’t perfect, but both sides felt they had an understanding on where the red lines lay. This new era has none of that.”

Fiona Hill, a former White House adviser on Russia, has said of the nuclear question: “Every time you think, no, [Putin] wouldn’t, would he? Well, yes, he would. And he wants us to know that, of course.”

Russian troops have already begun leaving the Chernobyl nuclear plant after getting “significant doses” of radiation.

Yet nuclear weapons release not just huge explosive power but deadly radiation as well – tens of thousands of people who survived the blasts in Japan later died of radiation poisoning. Breaking a city siege with nukes, even low-yield ones, would cause serious ecological fallout for Russian troops moving in, Ryan says, and “cross the Rubicon on nukes” for a job that could have been done with regular bombing.

Trying to disguise such an attack, say by instead deliberately destroying Ukraine’s nuclear power plants – which include the largest in Europe – would also make occupation more complicated, although recent Russian attacks on plants suggest it may happen accidentally. Russian troops have already begun leaving the Chernobyl nuclear plant they captured on the first night of the invasion – the scene of the world’s worst nuclear meltdown in 1986 – after getting “significant doses” of radiation from digging trenches at the contaminated site.

“Now, the one thing they might use nukes for is to destroy a significant concentration of the Ukrainian army,” Ryan says. “Because that’s hard to kill. So that would probably be the most likely target, not a city.”

While the Cold War focused on shows of terrifying power that neither side dared unleash for real, many experts say smaller, tactical nukes are now the big threat as they could rapidly escalate a conflict. Both the US and Russia have been improving their designs in recent years – Russian military doctrine allows for their use, as well as chemical weapons, to “defend Russia”.

Speaking of the Ukraine invasion in March, former Russian president Dmitry Medvedev reminded his audience that such a strike could be triggered even without an enemy using nuclear weapons first, adding that Russia was determined to “defend the independence, sovereignty of our country, not to give anyone a reason to doubt even the slightest that we are ready to give a worthy response to any infringement on our country”.

Given Putin has declared Ukraine is still part of Russia (despite the nation becoming independent in 1991), Ryan says the question of exactly what territory Russia considers its own is now crucial.

Still, he thinks that Russian policy on tactical nukes is as much for show as anything else. “The problem is when you call their bluff, and they seem to be not as tough as they’d been telling everyone – kind of like the US in Iraq in 2003 – what do they do next?”

Some analysts say Russia’s nuclear tough talk may take it all the way to detonating a warhead somewhere remote, at high altitude or even over the Black Sea, to demonstrate its willingness to use nukes and so frighten the Ukrainians into concessions at the negotiating table. Russian policy states that “in an escalating military conflict, demonstrating readiness and determination to use force using non-strategic nuclear weapons is an effective deterrent”, which has been interpreted by some analysts as describing a single nuclear detonation or launch.

Former US intelligence official Christopher Chivvis writes that scores of war games carried out by the US and its allies have predicted Putin will launch a single nuclear strike if threatened. A demonstration explosion could “make the lights go out in Oslo” and trigger a response in kind from NATO. Even if both sides stop at demonstration detonations, the nuclear taboo will have been broken, “and we are in an entirely new era”, Chivvis writes.

The empty control room of the shuttered Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, now under control by Russian forces after a fierce battle in the radioactive exclusion zone.Credit:AP

How would NATO and the West respond?

So far, the US has called Putin’s bluff and not raised its own nuclear alert level to match Russia’s. But if Russia uses tactical nukes in Ukraine, Ryan says it will be “a major trigger for NATO”, one that Russia has likely war-gamed already.

Sarah Bidgood, of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies in the US, also puts the likelihood of nuclear weapons use at “low though not zero”. She says NATO hasn’t gone into detail about how it would respond, beyond threatening consequences, in order to retain its “strategic ambiguity”. That means “keeping an adversary guessing about where your red lines are” and the exact consequences for crossing them in the hope it inspires restraint, she says.

But in Geneva, expert in Russian nuclear forces Pavel Podvig says NATO doesn’t have many options: “If Russia demonstrates that it’s willing to take greater risks and that its stakes in the conflict are higher, there is a good chance that the US [and] NATO will back down rather than face a prospect of nuclear confrontation with Russia.”

A major Princeton University simulation war-gaming a nuclear escalation between Russia and the US predicted 90 million people could be killed in tit-for-tat strikes within the first few hours of such a conflict. Past simulations have offered similarly sobering results – even when just a warning shot is fired, it often ends in nuclear strikes on cities. Alexander Vershbow, a former deputy secretary-general of NATO, told The New York Times that Western leaders had concluded Russia was sincere in its plans to use nuclear weapons in a major crisis, meaning any misstep that the Kremlin mistakes for war could escalate fast.

After US President Joe Biden exclaimed publicly of Putin “this man cannot remain in power”, some worried the Kremlin might buy its own propaganda about a Western plot to overthrow Putin. Such a concern would possibly drive the Russians to strike first, although other experts say Putin likely still feels secure in his position after more than 20 years rebuilding Russia into his vertical of power.

“Someone once described [the Cold War] as a barfight where the two biggest blokes punch everyone except each other.”

Of course, with the war on NATO’s doorstep, an attack could also spill across borders accidentally. Ukraine is not a NATO member but those in the alliance are bound to defend neighbouring NATO countries if they come under attack. Already Russian strikes have hit close to the border of NATO member Poland, decimating a base previously frequented by Western military trainers, and days later hitting near supply lines from NATO countries. As Biden visited Poland, Russia was striking the nearby city of Lviv in Ukraine’s west.

Podvig says it would be a big escalation for Russia to attack NATO territory “very unlikely, but probably not impossible”. What if Russia wanted to block the supply chain of weapons from NATO countries? “If something like that happens, NATO might retaliate (conventionally, of course) against some Russian targets … Would Russia decide that the situation ‘puts the very existence of the state in danger’?”

Some experts say, at the very least, a nuclear attack on Ukraine could propel NATO into enforcing a no-fly zone over the country to protect civilians from Russian bombing. That is something NATO has so far resisted as it raises the prospect of shooting down Russian planes – putting the West in direct conflict with Russia.

An intercontinental ballistic missile is driven along a Moscow street during rehearsals for Victory Day in 2020.Credit:Getty Images

What about deterrence – and regulation?

For the most part, nuclear deterrence has worked, says Ryan. During the Cold War, Russia and the US were careful to fight only proxy wars, never taking each other on directly. “Someone once described it to me as a bar fight, where the two biggest blokes punch everyone else except each other,” Ryan recalls.

Just before Russia invaded Ukraine, the major nuclear powers released a joint statement again swearing off nuclear war.

But Beatrice Fihn, who heads up the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, sees deterrence differently. The logic has always rested on “the nuclear-armed states being prepared to wipe out civilian populations,” she says. “Russia just said the silent part out loud. What Russia is doing now is deterrence in reality, that a person in charge can basically use it to blackmail the rest of the world.” Fihn says it’s impossible for Western democracies valuing human rights and the rule of law to “out-deter a dictator” with no such concerns. “In a nuclear game of chicken, rational people will always lose.”

Podvig agrees that, while “deterrence seems to work for Russia”, for aggressors, “it doesn’t quite work for NATO”. “This will require a serious re-evaluation and I fully expect that there will be people who would call for more nuclear weapons instead,” Podvig says.

People often talk about nuclear weapons in a cavalier fashion, he says, but such weapons “enable aggression”. “We should avoid normalising [them] and pretend that they somehow may have a plausible military mission.”

“In a nuclear game of chicken, rational people will always lose.”

International relations expert at the ANU Charles Miller says that, while the lines of communication are still open between Washington and Moscow, many Western policymakers thought nuclear weapons had become irrelevant in the years after the Cold War. “So this has come as a big shock to the system, not just psychologically but perhaps even operationally,” he says. “They haven’t thought about [nukes] as hard, they’re not as prepared to deal with nuclear coercion as they were during the Cold War.”

Ryan agrees that, since the mid-90s, nuclear deterrence has become something of a “lost art”. Now nations fight wars more tactically, he says, with counterinsurgencies. The US and China are among the countries beginning to move back to bigger, strategic plays as a new struggle between great powers emerges, he says, but “Australia has a long way to go”. “We have to do our own thinking on this,” he says, rather than relying on the US. “We’ll be a better ally for it.”

Miller says regulation of nukes has also dropped off. The Trump administration withdrew from the treaty on intermediate-range nukes, designed to limit US and Russia nuclear deployments, as well as the Iran nuclear deal that was set up in 2015 to stop Iran from developing its own nuclear weapons (and which is now being renegotiated by the Biden administration).

A South Korean TV news bulletin shows North Korean leader Kim Jong Un after his country conducted a nuclear test in 2016.Credit:Getty Images

Smaller nations, notably North Korea, have sought nuclear weapons as a kind of shortcut to beef up their militaries and so their standing on the world stage. Ukraine’s government has said it regrets giving up the nation’s nukes in light of Russia’s attack. Politicians in Japan and South Korea have made noise about hosting US nukes, rattling China, and Kremlin ally Belarus, which neighbours Ukraine, has changed its constitution to allow it to host Russian nuclear warheads.

“And when one country gets [nukes], all its neighbours want them,” Ryan says. “It’s why Japan, Australia and others are so keen to keep America in our region. If we don’t have America, potentially some countries will go nuclear, which would mean a breakout of nuclear weapons across Asia, and no one wants that.”

But he thinks the theory that a small arsenal of nukes deters attack is yet to be properly tested, even for all the attention Trump paid North Korea during (failed) efforts to get it to stop testing missiles. “If you only have a couple, and we know where they are and can take them out early, how good was your nuclear deterrent, really?” That’s why North Korea’s nuclear threats have not triggered the same fear among analysts as Russia’s.

The moment at a UN Security Council meeting when the US ambassador confronted the Soviet with photographs of Russian missile sites in Cuba on November 1, 1962.Credit:Fairfax Media

What can we learn from past close calls?

In a nuclear standoff, the pressure to “use or lose” weapons before an enemy fires can lead to nervy predictions. The emergence of hypersonic missiles, which can travel faster than the speed of sound and better evade radar, have shrunk reaction time windows further – and that means countries may be more tempted to attack rather than lose their only chance before a bomb hits.

Some of the most perilous moments of the Cold War happened when countries manoeuvred to reduce their opponent’s reaction time, including most famously in 1962 during the Cuban missile crisis. The Soviet Union had been secretly installing nukes in Cuba, a mere 160 kilometres from US territory, and president John F. Kennedy ordered a naval blockade to stop them. The standoff ended only when the Soviets agreed to dismantle the nuclear sites in exchange for a US pledge not to invade Soviet ally Cuba.

The potential for technological malfunction or simple human error has always been high too. The 1983 film War Games tells the story of a teen hacker who accidentally accesses a US government supercomputer built to simulate a nuclear war against the Soviets – and almost starts World War III. The year the film hit theatres, a Soviet officer received a real-life radar signal warning that US missiles were on their way to Russia. Lieutenant-Colonel Stanislav Petrov’s job was to launch Russia’s missiles at the US. But, against policy and orders, Petrov refused to fire. An investigation later showed it was a false alarm: the Soviet satellite warning system had malfunctioned. Petrov became known, unironically, as the man who saved the world.

Stanislav Petrov in 2013. The late former Soviet lieutenant-colonel averted a potential nuclear conflict.Credit:Getty Images

Later that same year, the Soviets were spooked by variations to a routine NATO exercise that made it seem more realistic. The drill, called Able Archer, convinced the Soviets that the West was about to launch a pre-emptive strike against them. Only decades later, when Soviet archives were opened, did the West learn how close Russia came to starting a war based on the signals they were misunderstanding.“Wars generally happen not because of calculation but miscalculation,” says Ryan.

He compares Putin today to Hitler before the outbreak of World War II, when the Nazi dictator was invading his neighbours. “The Western world wrung their hands but did nothing about it [until] Poland was that one invasion too many – and Ukraine, potentially is that one invasion too many for Putin.”

Still, he adds, neither side are idiots. “They don’t really want to use [nukes]. But we’ve got to make sure that in our rhetoric, we don’t escalate things to a position where Russian posturing becomes reality because they have no other choice. We don’t want to paint them into a corner. That’s why diplomacy has got to continue. There could be a breakthrough in peace talks tomorrow.”

Whatever happens in Ukraine, Fihn wonders if the world will finally learn its lesson on nuclear weapons: “If we survive this conflict without seeing nuclear weapons used … are we going to wait for another country to do the same again, or are we going to do something about the problem?”

If you'd like some expert background on an issue or a news event, drop us a line at [email protected] or [email protected]. Read more explainers here.

Most Viewed in National

Source: Read Full Article