In late 2021, as winter dawned on Beijing, a group of Chinese theorists, ministers and spin doctors came together to set out their plans for a new era of government – one they hoped would allow the Chinese Communist Party to remain in power forever while giving it the international respect it craves.

They were annoyed at the optics of China being snubbed from US President Joe Biden’s Summit for Democracy, had grown frustrated at China’s economic power not being matched by its diplomatic clout, and were anxious to avoid the endless cycle of rise and fall that has bedevilled China’s empires for millennia.

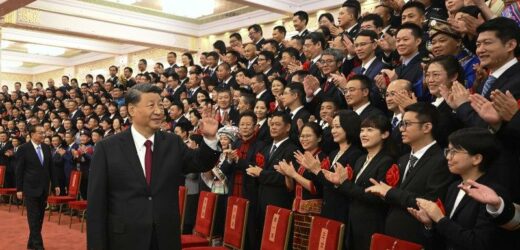

Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in August. Credit:AP

China’s President Xi Jinping was preparing for his crowning achievement at the National Party Congress this October – a third term in office – a feat not achieved since the death of Chairman Mao Zedong in 1976.

In meetings in the capital, the officials at the State Council Office sharpened their line of attack on the West’s version of democracy. They argued it was full of selfish politicians, broken campaign promises and fragmented societies.

“There is nothing wrong with democracy per se,” the advisers offered bluntly in a 50-page white paper. “Some countries have encountered setbacks and crises in their quest for democracy only because their approach was wrong.”

“Democracy with Chinese characteristics,” they said, could unite countries behind their long-term economic goals and guarantee stability.

The launch of the white paper in December was a brash affair. Fronted by Guo Zhenhua, the deputy secretary general of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress and Xu Lin, the minister of the State Council Information Office, it was largely dismissed by the West because of its colourful language (“China will fight with all the means necessary to hunt down tigers, swat flies, chase foxes”), contradictions and propaganda.

A screen displaying a People’s Liberation Army ad in Beijing. Credit:Bloomberg

But between metaphors, the white paper contained a plan not just for China’s future, but the push to export China’s model and burnish Xi’s legacy as he becomes the most powerful leader since Mao.

“China did not duplicate Western models of democracy, but created its own,” the State Council said. “It all boils down to whether the people can enjoy a good life.”

They argued what defined democracy was not whether one person had one vote, but whether the government fulfilled promises and enforced the rule of law.

“There is no fixed model of democracy,” the State Council said. “Whether a country is democratic should be acknowledged by the international community, not arbitrarily decided by a few self-appointed judges,” referring to American-led multilateral groups such as the Quad, Five Eyes and the G7.

In a message designed to appeal to other autocratic governments seeking democratic clout, the State Council said as a populous country long plagued by weak economic foundations, China had to strike a balance between democracy and development. One could be sacrificed for the other when circumstances required.

“The priority always rests with development, which is facilitated by democracy and in turn boosts the development of democracy.”

The advisers acknowledged that in China’s version of democracy there were no opposition parties, but argued that “China’s political party system is not a system of one-party rule”.

“The [Communist Party] is the governing party, and the other parties accept its leadership. They cooperate closely with the Communist Party and function as its advisers and assistants.”

In China, villagers can vote in local elections for Communist Party candidates. Those local representatives then vote for the leaders above them at the regional level, a pattern that is repeated all the way up to the National People’s Congress.

This model, Xi’s advisers said, avoided the West’s weaknesses of politicians acting in their own interests or those of their parties, showering campaign promises while campaigning, breaking them once elected, and fuelling division in society.

“This is most encouraging to developing countries and greatly enhances their confidence in developing their own democracy,” the State Council said. “China’s new approach to democracy represents a significant contribution to international politics and human progress.”

But there was a problem. China’s Constitution describes it as a dictatorship. Xi’s advisers had to work out how to marry democracy and dictatorship for an international audience.

“Democracy and dictatorship appear to be a contradiction in terms, but together they ensure the people’s status as masters of the country,” they said. “A tiny minority is sanctioned in the interests of the great majority, and ‘dictatorship’ serves democracy.”

Mao had a formula for this tiny minority: 95 per cent of people are good, 5 per cent are bad – including the activists and agitators that resisted one-party rule.

The white paper did not mention Mao’s other formula: “Political power grows out of the barrel of a gun” or the sworn loyalty of the People’s Liberation Army to the party, not the country.

“When they say, the democratic people’s dictatorship, what they mean is that the party exercises dictatorship on behalf of the ‘people’, as opposed to the ‘people’, who include ‘bad elements’,” says Linda Jaivin, an Australian sinologist and author of The Shortest History of China.

“In Chinese communist conceptions of ‘the people’, those loyal to the party and its aims get to be represented by the party, which means the party speaks in the name of the people, not that it has to listen to majority opinion.”

Sinologist and author Linda JaivinCredit:Anthony Johnson

Fellow Australian sinologist Geremie Barmé lauds the ingenuity of former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping’s rebranding of socialism with “Chinese characteristics” a term that has now been slapped across China’s economic, business and democratic theory.

“It really stems back to that brilliant and very simplistic innovation,” he says. “As soon as they came up with that concept, that such and such a thing can be rebranded with “Chinese characteristics”, then it allows every other thing to be rebranded and reformulated according to the national situation and traditions of China.”

Jaivin spoke alongside Barmé at the Sydney Opera House’s Antidote Festival last Sunday. The pair met and married in China (and are now divorced), but after decades of studying its language, culture, and politics, both are alarmed at the direction taken under Xi, the Chinese president who has purged his rivals, rapidly expanded state control and crushed Chinese civil society.

“The danger is that when you do that through a personality cult and the suppression of all dissenting views, then ultimately history turns on you,” says Jaivin.

“He’s got a messianic sense of mission,” says Barmé. “He is named as really the alpha and omega of the Chinese people – the solution to all of their problems.”

Barmé first met Xi’s father Xi Zhongxun in 1981 when he was working on Deng’s special economic zone in Shenzhen. By 1983 Xi the younger would become the secretary of Zhengding County in Hebei, his first step towards becoming a key member of the next generation of Chinese leaders.

“I’ve always been aware at some point, this group, who became particularly activist teenagers early in the Cultural Revolution, will be in a position to inherit power. The majority of them went on to carve up the country and become China’s wealthy billionaires.

“A few of them decided to pursue politics. They are now the standing committee of the Politburo.”

Barmé says China’s civil society, academics and progressive thinkers have watched on with despair as their country has become more nationalistic, sensitive and insular under the rule of Xi and the children of the Cultural Revolution.

“It was such a welcome relief when you had Donald Trump in power in the United States because now you can all understand how educated sensible Chinese people feel about their government,” he says.

Xi, who, unlike Trump, rules without the threat of a direct democratic election, now has unparalleled power at home. Chinese media reports suggest the 69-year-old is likely to be named as either the People’s Leader or Chairman at the National Party Congress on October 16.

But he faces trouble overseas, where China’s growing aggression towards Taiwan, bellicose diplomatic rhetoric and COVID-19 response have isolated it from advanced economies. China’s push to rebrand democracy is part of its global outreach campaign to developing countries that feel isolated by the West.

It has found some sympathetic ears at home and abroad.

China’s civil society, academics and progressive thinkers have watched on with despair as their country has become more nationalistic, sensitive and insular.

“Democracy cannot be reduced to what Americans call liberal democracy,” University of Sydney politics professor John Keane told China Daily earlier this month.

“The Chinese mode of government contains democratic qualities that should not be dismissed. There is a very strong sense in the political system, that power ultimately rests in the hands of the people. Any government attempt to violate that principle will end badly.”

Keane listed village elections, online question and answer sessions and an app that allowed residents to monitor and report on the quality of their water as democratic innovations.

“So-called Western democracies have their own system and China has its own democracy system,” says Wang Huiyao, the president of the Centre for China and Globalisation. “China is so big, the largest communist country and the world’s second-largest economy. Western countries are not doing that well. I can see if this is not properly explained people feel threatened.”

Despite Wang’s optimism after three years of COVID-19 controls, China’s economy is struggling more than its leaders would like it to be.

The Communist Party has up to 100 million members and most of those have partners, parents or children associated with their party status. “Up to a quarter of China, if not more, is directly linked to the party and benefits from its rule,” says Barmé.

They are acutely aware of the symbolism of China’s 20th Party Congress for building confidence in the party’s mission.

“When you look at the way the Communist Party has handled history from the beginning. It’s a series of erasures. They erase the party’s own mistakes and boost its accomplishments,” says Jaivin. “They’re very aware of the history of the Soviet Union and its collapse.”

Soviet leaders Vyacheslav Molotov, Nikita Kruschev and Joseph Stalin in 1934. Credit:Life Magazine

In 1956, at the Soviet Union’s 20th Party Congress, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev denounced former dictator Joseph Stalin for his cult of personality and reign of terror. Stalin had died three years earlier, but the speech sent shockwaves through Eastern Europe. By the 1980s, the flow-on effects of the speech had created the conditions for glasnost, the policy of transparency introduced by Mikhail Gorbachev in the 1980s that eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the collapse of communist rule in Moscow.

“For the first time, with glasnost, people had a very clear perspective on all the mistakes and all the horrors inflicted on the people of the Soviet Union by the party. They thought why the hell are we run by a communist party that has been so economically incompetent and politically cruel?”

The Chinese Communist Party, through its strict censorship, historical revisionism and democratic rebranding, is trying to make sure the same can never happen in Beijing.

“Everyone thinks it’s just economics and these are rational actors who just fit within the general neoliberal view of the world,” says Barmé. “But they fail to see how [the party’s theories and texts] actually function as a meaningful form of communication and governance, and how it underpins everything.”

Get a note directly from our foreign correspondents on what’s making headlines around the world. Sign up for the weekly What in the World newsletter here.

Most Viewed in World

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article