The cool girls did it in the locker room.

It was a rite of passage into womanhood, like first bras or periods: slapping pigmented goop onto still-growing thighs, using green paper towels to ensure full coverage and an acrid smell like burning plastic.

At the time – as a 12-year-old brown girl in an extremely white year group – I was shocked to discover this was legal. Blackface and cultural appropriation was wrong. How could changing your own colour be allowed?

I have boycotted fake tan ever since. I was bullied due to being brown – nicknames like ‘Curry House’ and ‘Apu’ were hurled at me, and I was told I was the ‘colour of poo’ as early as primary school.

The audacity that other people could be celebrated for becoming the thing I was punished for seemed cruel and unjust. It took me into adulthood to work through the years of bullying and to unlearn that my skin colour made me ugly.

20 years later, fake tan is a multi-million-pound industry run on insecurity. Almost every online beauty store has a dedicated ‘tan’ section and articles on furtive tanning ‘secrets’ abound.

Fake tan is not just normalised and accepted, but thriving. It’s one of the most openly accepted double standards of white privilege – while people of colour face violence on how we look, white people use our appearances as a fashion trend.

It’s ironic, too, that white people are regularly aghast over skin bleaching – citing health risks, patriarchal beauty standards, and lack of market regulation as reasons for being ‘bad’.

The same could be said for some tanning methods.

The fact that fake tan affects people who are actually ‘tanned’ seems obvious. As well as messing with the self-perception of people of colour (back at school, aged 12, I’d wondered if white people were now my colour, did I need to be darker? Where does it end?), encouraging appropriation and consigning race to a seasonal trend, fake tan relies on anxiety.

It tells you that your actual skin is not enough. Using it creates a feedback loop. With no clearly-defined end goal, you are committed to reapplying fake tan when it fades, or upping your usage to appear correspondingly darker as time goes on.

Insecurity is fostered through celebrating those who tan ‘correctly’, appearing ‘glowy’ and ‘bronzed’ or chastising those who look ‘pale’ or ‘streaky’.

Another huge hypocrisy present in fake tan usage is that people of colour naturally face bias, racism and oppression due to their skin tone – oppression that only increases with how dark you are.

Consider what a lack of representation for people of colour means. I have been asked what fake tan I use, and one time faced confusion from a white person who couldn’t believe that my entire body was the same colour, leaving me blankly staring back and trying to work out if they were joking.

I don’t take this as a compliment: comments like this undermine my existence, suggesting that people are genuinely taken aback that others can be brown without using fake tan. How few brown people must have you encountered to issue this query to me?

In recent years, the line has only been further blurred – with videos on social media where people try to guess who is South Asian and who is white.

In late 2018, I began a conversation with my followers on Instagram about fake tan. It was prompted by Ariana Grande’s ‘thank u, next’ music video, in which white singer Ariana Grande appeared to look around the same colour as I am.

I had gone into the conversation furious that this look was apparently not just normalised but celebrated as desirable. My followers largely agreed with me, though we diverged over whether fake tan as a whole was acceptable or not.

Many of my PoC followers had similar stories to me about their white friends becoming similar shades to them, and voiced similar feelings of alienation.

I was also surprised by the outpouring of emotion from white women, many of whom were upset and said they were frustrated and tired with fake tan, but still felt compelled to use it.

Many of them mentioned ‘inheriting’ an obsession with using fake tan, referencing comments from their mothers who thought they looked healthier after using it, or needing to ‘live up to’ older siblings in family portraits. Some women even cited being bullied for their ‘pasty’ complexion at school.

As somebody who was also bullied for the colour of their skin, I don’t think the solution is ‘I was bullied for being white, so I should go darker’.

I think the question is: How can you accept being the shade you are? There must be a way of dealing with insecurities that doesn’t involve further inflicting harm on already marginalised people.

Many white women I spoke to also held a double standard over fake tan usage. They disagreed with sun beds and tanning pills, but used fake tan moisturiser, for example, or they cited an imaginary ‘line’ that they would not cross that somehow made them a more ‘appropriate’ user of fake tan.

All fake tan usage exists on the same spectrum – changing your skin colour ultimately serves to uphold the same system of double standards, and issues of insecurity over your ‘natural’ colour.

It’s not OK to praise white people for using their skin colour as a trend while people of colour face real oppression due to that same skin colour.

Fake tan is a waste of time, money, and energy.

That so many people profit from others’ insecurity seems immoral to me, and it would be nice if we could focus on – and celebrate – other areas of our appearance.

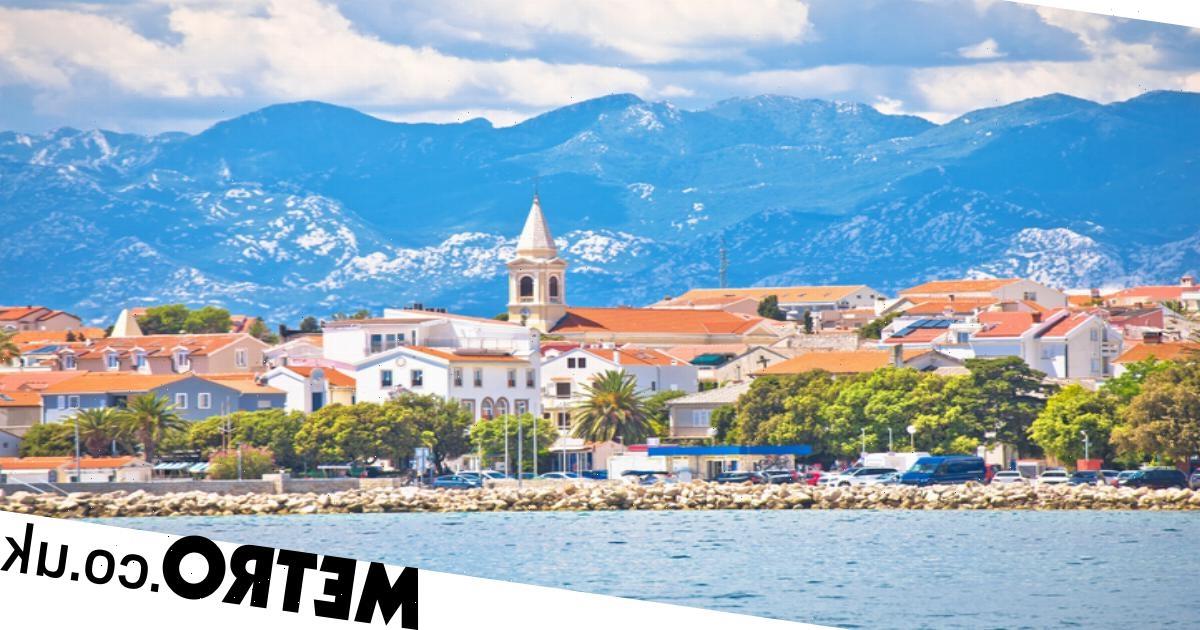

I live in the northern hemisphere, where it is mostly cold, grey and rainy. The idea any white person would be tanned and ‘sunkissed’ year-round is absurd, and seems a truly ridiculous standard to try and maintain.

It’s time to put down the application mitts, switch off the sunbed, put down the tanning pills, fold away the spray tent, sack it off, and learn to start existing in your own, un-fake tanned skin.

Not Quite White by Laila Woozeer (£16.99, Simon & Schuster) is out now and is available from Amazon and all good bookshops.

The Truth Is…

Metro.co.uk’s weekly The Truth Is… series seeks to explore anything and everything when it comes to life’s unspoken truths and long-held secrets. Contributors will challenge popular misconceptions on a topic close to their hearts, confess to a deeply personal secret, or reveal their wisdom from experience – good and bad – when it comes to romance or family relationships.

If you would like your share your truth with our readers, email [email protected].

Source: Read Full Article