City Of Mirrors, the new album from the Chicago quintet Dos Santos, feels like it’s perpetually building and expanding. Cumbia rhythms rise from the production and mix with jazz melodies; a sudden huapango structure might jut out from a chorus or intro. Since coming together in 2013, the band has always had an effortless way of mixing genres and Latinx traditions, but the bolts are tighter than ever on this project — and the subject matter is weighty and pressing, marking an imaginative step forward for a band that’s never limited itself to begin with.

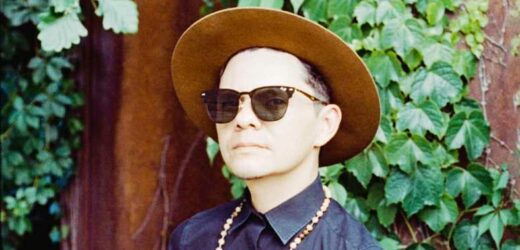

The album, as the name suggest, is full of reflections of who the band is and of what was happening around them during the writing and recording process. It marked the first time they had worked closely with a producer: They teamed up with Elliot Bergman of the psych-pop band Wild Belle and recorded a lot of the music in Los Angeles, employing an open-ended, freewheeling approach that resulted in a spontaneous and refreshingly experimental set of songs. Through it all, the country was roiling with catastrophes at the border and failures of the previous administration, tumult that deeply impacted the members of Dos Santos, who include bassist Jaime Garza, guitarist and vocalist Nathan Karagianis, drummer Daniel Villarreal-Carrillo, percussionist Pete Vale, and vocalist and multi-instrumentalist Alex Chavez.

“When we were making this record and writing for it, there were the zero-tolerance policies at the border, the separation of families, all of that violence throughout the United States against Latinx communities,” Chavez says on a recent Zoom call. As they were finishing the album last year, the pandemic started. “There’s no way if you’re making art that your mind isn’t going to go there and that those things aren’t going to be dragged into view,” Chavez adds. “There was no moment that wasn’t a moment of crisis.”

Songs like the title track examine the resilience of Puerto Rico, where Vale’s family is from, while “Cages and Palaces” directly confronts violence against migrants at the border. “Palo Santo,” meanwhile, lauds necessary social change and revolution — alluding to the racial reckoning that was happening in the country after the murder of George Floyd. What ties everything together is the band’s eagerness to constantly explore new directions. Chavez and Karagianis went into detail about the making of City Of Mirrors and the improvisational creative leap it represents.

The theme of borders plays a big role on this album. There’s a description the band wrote that describes the borderland as “the forbidden place where we dwell.” What did that mean to you, and how else were you thinking of borders here?

Chavez: We’re very conscious that on the one hand, we’re informed by a number of different genres, just by virtue of who we are, so there’s this transgression between sounds that’s part of who we are. We’re always there in that in-between space. And we always recognize that we’re not just making this music, but we’re making it in a specific and situated way: As Latinos in the U.S. Inherently, what we do speaks to multiple audiences, and it’s informed by this hemispheric experience that’s migratory — all these things that when it comes to Latino music in the United States, you necessarily have to think about. At a conceptual, artistic level, there was the idea of borderlands that was informed by tall of that.

At a literal level, when we were making this record, there was a lot going on, which continues today. We just saw everything with the Haitian migrants at the border… That was part of what was informing us, at least lyrically. And then no less, Covid is happening, and everything is sort of cascading. Even towards the end, when we were beginning to mix the record, everyone is taking to the streets in the wake of the George Floyd killing. That struggle also has to do with borders: Not the literal U.S.-Mexico borders, but the borders of American belonging — who’s allowed to have full citizenship as Black people and people of color. Thematically, all of that is in there.

This album is the first time you’ve worked closely with an outside producer. What was the process of working with Elliot Bergman like?

Chavez: We as an entity have always been connected to multiple aspects of the Chicago music scene, across genre and communities, and Elliot is a figure here. I think he’s most well-known for two projects: No Mode, which is this Afrobeat-inspired project that’s really experimental and that we were fans of, and Wild Belle, the duo with his sister, Natalie Bergman. Some of us had met him before — our drummer knew him a little better than most of us because he played and went on tour with Wild Belle for a little bit, so there was a personal connection. With the last record, Logos, we went into it producing with the label itself, but we were kind of flying solo in a sense. With this one, the intention was to bring someone else in to help produce for several reasons. Maybe chief among them is wanting to step outside of ourselves. When you have someone lend their ear to what you’re doing, it gives you a completely different perspective — it can push you and lead you to certain creative ways that maybe you don’t anticipate that can be amazing. We continue to have this respect for Elliott’s sonics — he has such a discerning ear and he’s very much an appreciator of all kinds of music, particularly a lot of the ones that touch what we do. So, for us, it’s good to have somebody who has those references to genre or tradition in a way where you’re sharing a kind of language around what you’re trying to do.

Karagianis: The first thing I remember about Elliott was we did Psych Fest with him in Chicago at this place called the Hideout. His band at the time was an outfit he calls the Metal Tones, which is a great improvisational thing where he’s using these made objects that are like big kalimbas, and it was incredible… Elliot is an artist and he deals with tangible things: He’s making these incredible art installations, and he’s very much connected with the tangible aspects of making sound. There’s this 3D approach to his work, and I think that’s reflected in the album, with all the different things that come in and out.

Compared to when you were flying solo before, how did working with Elliot change the sound of the record?

Chavez: It gave it a completely different character. It’d be disingenuous for me to say that I anticipated the ways that that would happen, because I had no idea. I don’t think anybody did. We respected Elliot as an artist, like Nathan mentioned, and we knew that it would be an adventure. But we didn’t know where we were going necessarily, and that was part of the excitement and the fun… We had a number of things that we brought to the table. Unlike what we’ve done before, where we go into the studio and kind of document things that are road-tested — the things we brought, we’d never played live, with the exception of one time. Walking into it that way, we know we had this scaffolding, but we had to build a lot, and we knew what we had written would change, by trying things out or Elliot pushing us or contributing ideas. The other aspect was things that he brought to the table that we also expanded… When you truly use the space of the studio, or rather the time of the studio, as something generative, it’s like you’re both literally and figuratively playing. We were having fun. It was a game of, “Oh, what are we doing now? What can we create now?” There’s something incredibly improvisational about that, which is an element that we bring to what we do live.

Karagianis: Early in the process, Alex and I had come together to collaborate a little bit, to work on some ideas that were part of some generative exercises that Elliot placed in front of us [before going to Los Angeles to finish the album]. All of a sudden, I asked Alex, “What do you think we should anticipate? What’s this going to be like when we get out there?” And he was like, “I don’t know.” I’d never heard Alex say anything like this before. Usually, he’s got some very concrete ideas of what a certain experience might be like. I was excited by the prospect that he was like, “We’re just going to show up and do what we do, and literally let’s just show up, and be present, and see what happens.”

We improvise a lot, and we do things to be present, and I think Elliot was a good impetus of that and empowered a lot of those things in us. We have different backgrounds and there are so many things that we’re capable of doing. We definitely trusted Eliot to lead us into a bit of the unknown, and willingly, we went along.

Each member of the band represents different styles, backgrounds, and traditions, particularly from Latin America. Sometimes in music, that can come off sounding generally pan-Latin or flattened in an uncomfortable way, but all these influences coexist organically on this album. How do you guys think about each piece each member is bringing to the table?

Chavez: Maybe one aspect of it is that compositionally and sonically, we don’t have very many conversations. In other words, it’s not overwrought. It’s not like, “Hey guys, I want to write this cumbia that then goes into this rhythm.” … There’s a trust that if I’m bringing an idea, we have a sense of maybe where the pulse might be, the heart of it, but everybody begins to distill it in ways that they hear… One example is the first song, “Shot in the Dark.” [At one point,] Elliot was like, “Go sing,” to me. I was like, “Well, in the spirit of being in the moment, I’m not going to sit down and write something.” One of the things that I always draw on both, lyrically and compositionally, are verse structures from huapango music, because that’s what I know, that’s what I grew up with, that’s something that’s in me. I remember I just went up to the mic and Elliot perked his ears up. He was like, “Oh man, that sounds good.” I was like, “Yeah, these are just traditional verses, like as a placeholder.” When I heard it back, I was like, “Let me do it again,” and I went for it, and that’s what you hear on the record. I wasn’t like, “Hey guys, we should do a song that’s like a huapango!” It just became this magical thing on this particular session where we’re like, “Man, what is this?”

Karagianis: That was an interesting song for sure. There were several things that I wanted to try while working at Elliot’s studio. I looked at this Mellotron that Elliot had and I was like, “Man, I’ve never played a Mellotron before. Let’s see what this is all about.” I started to flip through. We’re on the West Coast making this record, and when I think about the West Coast, I think about the beach, I think about the waves and the Beach Boys. At some point, when I hit this sample, I was like, “Oh, wow. That sounds like the Beach Boys.” I remember looking at Elliot and Alex and everybody’s eyes sort of just kind of got a little wide. Elliot was like, “Wow, that, what is that?” I was like, “It sounds like the Beach Boys, you guys. I don’t know. This is sweet.”… I think I remember Elliot saying something about how there’s this spiritual sort of feeling about that song, maybe a little bit of transmutation from some of the energy that was going into the recording. It really shifted at that point.

Chavez: It opened this world where a huapango verse can meet this lush, almost sensual melodic thing going on between guitar and bass. Then there’s Bata drumming samples underneath it. If you talk about how to make that, you’re not going to make that. It’s just not gonna happen [laughs.]

Source: Read Full Article