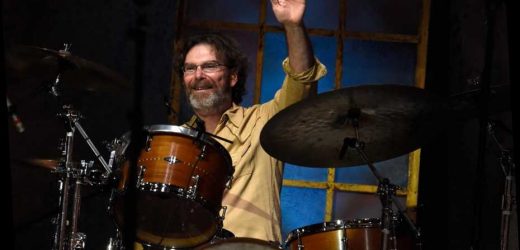

A few months back, Chad Cromwell got a phone call from Neil Young totally out of the blue. “He said, ‘Man, you’re on my mind,’” says the drummer. “‘I’m going through a lot of film and tapes and I hadn’t talked to you in a while and just wanted to reach out and say I love you and I miss you.’ It was beautiful. We’re veterans together and the call meant a lot to me.”

It’s unclear what exact footage Young was referencing, but his vault is overflowing with video and audio recordings where Cromwell is behind the drum kit. They first teamed up in 1988 for the This Note’s for You album and tour, and Cromwell was the drummer on Young’s landmark 1989 LP Freedom, which includes “Rockin’ in the Free World.” He came back in 2005 for Prairie Wind and stuck around for the 2006 CSNY Living With War tour, Chrome Dreams II, Fork in the Road, and the 2008–09 Electric Band world tour. Only Crazy Horse’s Ralph Molina and Buffalo Springfield’s Dewey Martin have played more shows with Young as a drummer.

Young may be Cromwell’s most prominent collaborator, but he’s also worked extensively with Mark Knopfler, Joe Walsh, Kenny Chesney, and Peter Frampton, and he’s a top-tier Nashville session drummer, playing with country trio Lady A, Trace Adkins, Miranda Lambert, Blake Shelton, Bob Seger, and too many others to mention.

Cromwell phoned up Rolling Stone to talk about his incredible career.

Have you been working much during the quarantine?

Yeah. Thankfully, the session thing has been careful and limited, but still fruitful. We’ve been doing some really good work. I’ve got a really deep working relationship with Dave Stewart of the Eurythmics. Just before the holidays began, we tracked a musical that he’s written, which is a huge body of work, and then right after that, we went in and recorded Joss Stone’s new record.

Somehow, the wheels keep turning a little bit. I’m really, really grateful for that. The only risk I’m taking on is getting on airplanes to go back and forth to L.A. That is a little tricky. I’m not so keen on doing that, but I chose this path in life, being a drummer and producer, and have gun will travel, right? [Laughs]

Let’s go back and talk about your life. Where did you grow up?

I grew up in Memphis, Tennessee.

What’s the first music you remember hearing that really struck you?

The first music that struck me was Mitch Miller. He had a television show [Sing Along With Mitch] back in the early Sixties. Back in those days, he had this thing where it was all about singalong music. You’d be standing in front of the television, like I was as a little kid, and you’d follow the bouncing ball going over the vowels and syllables on the bottom of the screen while this band and essentially a choir would sing these songs. It’s pretty corny stuff, but as a little kid, I thought it was super cool.

Prior to that, as a baby, I grew up underneath a grand piano because my mom was a classical piano teacher. That was probably my first musical influence, but I just didn’t know it.

Did you see any concerts in your early years that really stayed with you?

There was a place in Memphis called the Overton Park Shell. They had an outdoor concert summer series with different shows. The first show that I ever saw there, I had to climb a tree off property because I wasn’t old enough to get in, or I didn’t have the money. It was a Freddie King concert [on April 10th, 1971]. I got to see him and his band, which completely blew my mind. I had never seen anything like that. It definitely, definitely struck a chord with me.

But maybe more interesting and contemporary, is the opening band for him was ZZ Top, I think after their first record. And it was ZZ Top, those three guys. They were still pretty much a full-on blues trio. I remember Billy [Gibbons] walking onstage in fishnet stockings and hot pants. [Laughs] You didn’t see a whole lot of that. I think David Bowie was just beginning to blaze that trail around that same time. I just thought, “This is the weirdest shit I’ve ever seen in my life, but these guys are killer.” They really were. They just a phenomenally great trio, early on.

How young were you when you started playing drums?

I was eight years old when I sat behind my first drum set. It wasn’t my kit, but it was the first time I ever played. I went to a friend of mine’s house on Christmas day to see what Santa brought him and his brother. They got a red-sparkle drum set out of the Sears catalog that their parents brought them. The other brother got a Silvertone electric guitar with the amplifier built into the case. That was my first exposure to rhythm-section equipment.

I remember it like it was yesterday. I just sat down behind the kit and I started playing. I didn’t know what I was doing, but I was playing. Years later, I got much more serious about it. Initially, it was just something fun to do before baseball practice.

Who are some of your early drumming heroes?

My earliest drum heroes would have been Ringo and Buddy Rich. But far and away, the most influential in my life was Al Jackson [of Booker T. and the M.G.’s]. That being because I grew up in Memphis and Stax is where I learned so much of my music.

In Memphis in those days, you could go see Booker T. and the MG’s at a swimming pool party. I saw bands like that, like the Bar-Kays, at public swimming pool parks. That music got into my DNA. I wasn’t even sure whether I paid close attention to how great it was. It just was the fabric of my youth. You couldn’t get away from it.

In Memphis at that time, growing up in the Sixties, those were incredibly influential years for Memphis music and for the world, frankly, because of the things that came out of there.

How old were you when you started thinking about becoming a professional drummer?

I started really turning on to it when I was 12 or 13. That’s when I began feeling the calling of the late-Sixties hippie movement, like Woodstock. I was influenced by all that. I remember one of my Christmases getting the Woodstock cassette, the entire concert, and just digging the stuff I felt was really great about that. I was also still carrying on with the Memphis stuff.

When did you have your big break on a professional level?

Well, the first professional job, what I call a career start, was in 1975. I got asked to join a trio that consisted of a young guitar player in Memphis named Robert Johnson and a bass player named David Cochran. They were both original Memphians who had moved to London a couple of years prior to this gig I got.

I became Robert’s rhythm guitar player before he went to London. I then began working with Chris Spedding of the Sharks. Robert was playing guitar in John Entwistle’s Ox. They got the idea that they wanted to form their own band. Robert had a concept in mind. He wanted it to be a power punk trio with a Memphis bent to it.

David had flown home to see family. I ended him jamming with him at this funky old nightclub in Memphis called the Thirsty Elephant. That led to this invitation. Literally, two weeks after I graduated from high school, I moved to London and got into this band. We went into Mayfair Studio, recorded a bunch of music and we were one of the first signings to [Elton John’s] Rocket Records. It was us and Grace Jones.

Sounds like it was short-lived.

Yeah. Things from there sort of unwound in a not-so-good way. We ended up losing the deal about as quickly as we got the deal. It was one of those things where you think, “This is it! We got a record deal. We’re going to go on tour with Elton John. We’re one of his signings. Hey, this is it. I’ll be buying my BMW any minute.” Within four or so months, it went from “we’re going on tour and releasing a record” to “here is your ticket home. Go home now. It’s not happening.”

That was my first pro gig. When I got back to Memphis, I wound up in a band called Larry Raspberry and Highsteppers. I played and toured with Larry for a couple of years, and then came back when I really decided I didn’t want to be a road dog to that extent. I got turned onto being a studio player. I liked the idea of that.

Then I went into a mentorship with a guy named Bobby Manuel. His partner was Jimmy Stewart, the founder of Stax. They had a production company called Daily Planet. Those guys took me under their wing. They were the ones who I give a lot of credit to for guiding me toward the career that I’ve had, Bobby especially was enormously influential in how I shaped the course of my career. I’m so grateful to them for that. Everything he taught me, I still apply to this day.

To flash forward a bit, how did you wind up playing drums on Got Any Gum? by Joe Walsh?

I met Joe at a recording studio in Memphis where I worked a lot and did a lot of sessions. His girlfriend at that time was a very close friend of the wife of the studio owner. The two of them owned this recording studio that I worked at. When Joe came into town, he just came over and there was some sort of party going on. I was introduced to Joe. That was one of the strangest things because we just stayed up all night, acting like idiots, as everyone would do in the mid-Eighties.

The next thing I knew, Joe asked me to do a gig with him down in Dallas. He and Rick Rosas, the bass player, were doing guest DJ [spots] at the rock station in Dallas. He invited me to come to Dallas, spend a week rehearsing, and then we were going to go to L.A. and do a KLOS outdoor big concert thing that Joe was headlining. That was my first gig with Joe. The strange thing is, the entire week I was in Dallas, I was waiting to rehearse, but we never did rehearse.

We get on a plane and fly to L.A. We get off the plane and literally get in a car and drive out to Irvine Meadows. There are 20,000 people at this venue and I am shitting myself since I still haven’t rehearsed with Joe and Rick. [Laughs] I’ve just listened to tapes.

I remember walking onstage going, “OK! I’m probably going to be put on a plane home after this is over with, but fuck it. If he doesn’t want to rehearse, I’m just going with it with him. I’ll see what happens.”

We had an absolute blast! It was just magic. We definitely had some train wrecks and all that, but it was so much fun. My first two or there years working with Joe were trio-oriented. That’s my favorite time with him to this day. The three-piece thing, he’s just so good at it.

Leading up to Got Any Gum?, that connection got made because Joe and I met and had to do a handful of these gigs. I was a default call for Joe since he already worked with me. Then he came back to Memphis to work with Terry Manning. Terry was a resident engineer-producer who liked to do his recording at Ardent Studio in Memphis.

It’s a cool record, but there’s that Eighties drum sound …

I know. Terry is the same guy that did the Eliminator record for ZZ Top, which was all drum machine, played real time. Terry was pretty big on whatever the latest, coolest piece of gear would be at the time. There was a company called AMS — they made a gated reverb box and then a delay box that probably is most well known as the drum sound on “In the Air Tonight” by Phil Collins. Same gear, same box. If you listen to Got Any Gum?, you’re going to hear the same thing.

I remember thinking at the time, “This is the most incredible drum sound I’ve ever heard in my life.” I wasn’t really thinking about how dated that would sound 10 years later. But that was a lot of fun, making that record.

Tell me about meeting Neil Young. I’ve seen Neil say he first saw Rick Rosas at Farm Aid with Joe in 1987. Did he meet you there as well?

Yeah. We were playing a gig with Joe at Farm Aid [in Lincoln, Nebraska]. Neil was there, obviously. I remember him coming on the bus to hang out for a little while. For a while, starting with Farm Aid, we talked about the possibility of putting a four-piece band together with Joe, Neil, me and Rick. It just never came to be. We danced with the concept for a while, but it never happened. Joe did sit in with Neil at Blossom [for “Tonight’s the Night” on September 3rd, 1988].

How did you wind up recording with Neil on the Bluenotes record?

The guy that gets the credit for that is an engineer named Niko Bolas. Niko and I met on a record in Memphis that he was engineering for Rob Jungklas. We were working on his first record. Niko was hired to come in as an independent engineer to record those sessions. Niko and I became very good friends. I actually rented the second bedroom of my apartment to him while he was there. We became very, very good friends.

He was the reason that job happened. Neil just wasn’t happy with the drummers he was bringing in to do this blues-rock thing he was doing, a horn band. The cats that were coming in to play for him, that just wasn’t their wheelhouse. And so Niko said, “I know this guy in Memphis that can do this shit in his sleep. He’s a natural for this job.”

Neil, uncharacteristically, agreed to work with someone new. That doesn’t happen that often with him. He operates a fairly tight circle with his musical families. I got at least invited to SIR in Hollywood to take a swing at it. I rolled in there, Niko introduced me to him and Neil just looked at me, put his hand out and went, “Hey man, I’m Shakey.” That’s how we started. An hour later, we’re out there swinging. We were done tracking the record two or three days later. It kicked ass. We just got right on it.

Do you recall making the song “This Note’s for You?”

I do. We recorded this record remotely at SIR, at a rehearsal studio. An A&M recording truck was parked out in the street. We were just going along, cutting the music, and then he had this tune called “This Note’s for You.” I was like, “This is kind of like a placeholder for this concept.” We started with a mid-tempo eighth-note blues groove. It just felt really great, as soon as we started playing it. As we got into the story of the song, it just got better and better and better. It became the cornerstone of all that. It was really, really fun to cut the song.

What was also fun was doing the video at some club somewhere. I don’t even remember. I remember that being a lot of fun, too. It was like, “There’s something really sweet about this.” We were working on that video and I remember Neil saying to me after we shot it — we were in a little alley and he said, “Man, you guys just contributed so much to this record. I’m making arrangements to cut you guys in a little bit on this. I really appreciate what you’ve done.”

He made his word good. A year later, a check showed up at my mailbox. It was a down payment on a house. It was a shock to me. I really didn’t expect anything like that. But kudos to Neil for that kind of generosity. I love the guy dearly for his devotion to the music. I just love that.

At the early shows on that tour, you’re playing clubs and it’s just the new songs. Are you facing crowds that wanted “Heart of Gold” and were a little disappointed?

It’s a weird thing. Depending on what sort of frame of mind the audience is in, the fans are either there to hear “Heart of Gold” or they’re there to hear “Cortez the Killer.” You don’t know what you’re getting into. The thing about Neil that is so unique and special, he totally responds to that. It’s not like, “This is the set list and it’s the only one we’re going play tonight.” He would go off in left field and suddenly we’re not doing anything remotely like the Bluenotes. We’re playing fuckin’ “Tonight’s the Night.”

But for most of the early shows, it was just the Bluenotes songs.

Yeah. The [April 1988] shows at the World [in New York City]. That was full-on blues band, blues revue. Those audiences were probably going, “When’s he gonna do ‘Old Man’?” But that was never going to happen.

When you moved to sheds in the summer, suddenly it’s “Comes a Time” and “Lotta Love” in the set list. He got more flexible for the bigger crowds.

As musicians do, and songwriters, I think he was starting to feel that he’d gotten out the information that he needed to get out there from that time. You really started feeling rock & roll coming back into his psyche. After one of the legs of the Bluenotes tour, we went back in the studio again. That’s when we recorded what was going to be the second Bluenotes record. That is when we cut “Ordinary People.” That is also when “Rockin’ in the Free World” started to rear its head.

The Bluenotes end in October 1988. You come back just three months later, and suddenly it’s a whole new group called the Restless that’s you, Poncho, Rick, and Ben Keith. And you’re not doing any of the Bluenotes songs.

It was primarily Neil, Rick, and I. Poncho entered a little bit later [into the show] and Long Grain [Ben Keith] came in a little after that to perform some of the music. That was mostly three-piece grunge, basically. Eddie Vedder said that what we were doing when we were tracking that stuff in New York, that was the advent of the grunge scene in Seattle. I don’t know if that’s actual truth or not.

But you listen to the Neil Young and the Restless record [Freedom], that pre-dates Nirvana. The clean verses and the kick-ass choruses. That was three-piece. We tracked that stuff at the old Hit Factory in Times Square in the small room. It was a drum set, a bass rig, and two Marshall stacks in a tiny room. It was un-fucking-believably loud. We cut “On Broadway” there and some really cool stuff in that room.

A lot of that was going on at the same time we were doing another Bluenotes record. It just finally morphed out of the Bluenotes. They sort of evaporated.

The tour hits Seattle in February 1989, and you debut “Rockin’ in the Free World.” I’ve heard the bootleg of that night. The song was done. He had all the verses and everything.

That was the first time where all the verses were complete. It took him a while to completely write all those verses. When we did it in Seattle at the Paramount Theater, that was the first true final arrangement of that song.

What do you recall about making it?

That was in the barn [at Young’s California ranch]. He walked in and he had this big artist easel setup with a big, giant sketch pad on it and big magic markers. He and Poncho had this lick [hums it]. We just started playing, slamming eighth notes. The next thing I know, he’d be like, “Hang on a minute!” and he’d start writing words down. Then we’d get back on the riff for a while. This went on for days. He was shaping the lyric and getting the song together. Obviously, we knew that was a special song. But we had no idea how special it was going to be.

It’s so funny that through much of the Eighties he’s recording all this eclectic music that drives David Geffen so insane that he sues him. Then finally he breaks free, and he writes the exact song that Geffen wanted the whole time.

[Laughs] I know! And I’m not sure whether that was on purpose or not. It’s hilarious.

After this, Neil goes back to Crazy Horse and you go back to Joe Walsh for Ordinary Average Guy. I’ve spoken to Joe about this and he’s very open about the fact that he was drinking way too much and was just a mess during this time. How hard was it to work for someone in that state?

It was a difficult session. We did that record in Chattanooga. There was this place up on Lookout Mountain. That’s where we did it. We camped out and we stayed at the Chattanooga Choo Choo hotel the whole time we made the record. It was a hazy, substance-abuse, alcohol-soaked experience. There were some really cool things that happened on that record. There were some really, really cool things. Then there was also some of his not-best work.

I think Joe was trying to figure out, as a musician, where his path was lying. This is post-Eagles and he was a bit of a lost soul. He was trying to do the solo thing, but I think there was a part of him that was trying to get back to his band, the Eagles. He just kept trying to do his thing, but he was really having a tough time.

It was a lot of substance abuse and days without sleep and then we gotta go do a gig and he’s, like, barely there. It was rugged. There’s also a thing about that guy. He’s such a beautiful soul and such a pure musician. Life circumstances can lead us into strange places that we’d rather not be [in]. I think that’s what was going on with him. He was trying to figure out where he was supposed to be in his life. That finally happened.

The Eagles re-formed 1994, but they insisted he go to rehab first.

One of the biggest memories of my lifetime is the night before he went into rehab. He came to a little tiny restaurant on Sunset Boulevard that Rick [Rosas], the bass player, and I were eating dinner at. The guy who owned the restaurant, Ken Frank, was friends with all of us. Ken was an amazing chef. The restaurant was closed for all intents and purposes, but we were having dinner in the very back, just visiting. And Joe showed up and tapped on the door and Ken let him in.

He looked straight at us and said, “They won’t let me in the band if I don’t go to rehab. I gotta go to rehab.” He was just a wreck. It was heartbreaking. He was in such bad shape. The next morning, he went to rehab. He has been sober ever since. God bless him.

So the Eagles saved his life.

The Eagles definitely saved his life. No question about it.

How did your Mark Knopfler chapter begin?

Well, that was 1995. Mark had been coming and going to Nashville for a few years to interact with Chet Atkins and do stuff with him. He was on the heals of the [1991] On Every Street record. That was the last Dire Straits record. He was ready to move on with his career. He didn’t want to do Dire Straits any longer. He felt it was time for a change.

He started recording and interacting with Nashville session guys. He did several different sessions with different combinations of players. And then he found the rhythm section that became what we affectionally called the Ninety-Sixers. That was a pet name for our first tour together. [Keyboardist] Guy Fletcher from Dire Straits was also part of it.

The very first record we did was all Nashville-based guys, called Golden Heart. We met at a studio called Emerald Sound. We started cutting Golden Heart and it was just instant band. It felt so great. We became fast friends and were having a ball together. That started a 10-year run with him.

Dire Straits was this massive band. He could have just called this new thing Dire Straits and continued to play stadiums. The lineup always changed a ton anyway and nobody cared. But clearly he wanted to massively downscale.

Yeah. He wanted to separate and distance himself from arena/stadium rock & roll. He wanted to get back to the intimacy of writing songs and telling stories and having the ability to do that in infinite environments.

A decision like that is very rare in rock since it meant making a lot less money.

Yeah. But when a guy has sold over 100 million records and he’s the sole writer on every song, I don’t think he has to worry about whether or not he’s going to make his rent. I think it really became a matter of creative control. It was also a matter of his family life where he wanted to maybe redirect his energies to accommodate for them as well.

How was he a different sort of bandleader than Neil Young?

Completely different. Neil is pure instinct. He captures lighting in a bottle. And even if it cracks the bottle, it still caught the lightning, so it’s awesome. It might be a shitty performance of the song, but it’s a perfect delivery of the vocal and the lyric, which is what matters.

Mark is different. Mark is more deliberate about the performance of the music and the subtleties of the music and the dynamics and control of notes and interaction of all the different musicians involved. It’s a much slower, deliberate, drawn-out process. It probably leans more towards the high-fi end of production.

I love all the records, but Sailing to Philadelphia is a real favorite of mine. There’s a magic to that record.

That’s a great record, man. We cut that at a place called the Tracking Room in Nashville. That’s just a beautiful record, a real beauty.

During the concerts, there were brief moments where he’d do “Sultans of Swing” or his old arena-rock thing, but they were brief, almost the bare minimum.

I think he did that as an homage to his audience. Most people that go see him perform want to hear songs that changed their lives. If that happens to be “Money for Nothing,” but he doesn’t want to sing that, there are days where we’d go, “You know what, man? You gotta do that. You gotta give the people what they’ve given you.” That’s just the way it goes.

I think he serviced that as long as he could. I’m pretty far out of touch with Mark now. I don’t know what he’s doing with his recording and live performing. I can only relate to my time with him. I know that where we started on Golden Heart and where I dropped off at the end of my tenure with him, he had transitioned considerably in the direction of more of a folk songwriter kind of guy than a rock & roll guy.

You left the 2005 tour during the tour. What happened there?

That was personal things that were going on in my life that needed pretty intense attention. It was family-related. It wasn’t music-related. There were some professional issues that were unfortunate, but none of them would I ever direct to Mark. Mark was great. I still love Mark. But I needed to take a break during that tour.

The handling of all that got really tricky for me and it came necessary for me to say goodbye at that point. In all fairness to everyone involved, I can’t go too deeply into all that, but that was my jumping-off point.

That same year, 2005, you jump back to Neil Young after 16 years off and cut Prairie Wind.

That’s exactly right. It was right on the heels of that. A lot of people think I quit Mark so I could go play with Neil. That wasn’t the case. Neil had actually contacted me about recording while I was on tour with Mark. I just said, “I can’t do it, man. I can’t do it.” He moved on and started recording Prairie Wind [with Karl Himmel on drums]. When I left the tour, shortly thereafter, Neil decided to resume the recording again and Long Grain [Ben Keith] was aware of the fact that I was back in Nashville. Then he said, “Neil has come to town. Can you come record?” I said, “Of course I can. I’m here.”

I came down and started recording and basically took Karl’s place to finish the tracking, since it was almost done. That began a whole new chapter of my life professional with Neil, post-Mark. I know that those fans will always wonder about that. I can totally see why they would wonder about it. It’s awfully ironic that you’re leaving the band and joining Neil about a month later. But all it was was a session. It worked out. I didn’t hear another thing about working with Neil until Farm Aid.

Those sessions were pretty unique because he just had the aneurysm. It was a very uncertain and scary time for him.

It was beyond scary. The way we were recording that stuff was indicative of his concern because he didn’t want to record the songs, get them all tracked, and then come back and put a list of overdubs together and get whoever he needed on it. He insisted on cutting the track and finishing the record before we moved onto the next song.

I had a conversation with him in the parking lot of the studio. I believe that sometimes people are brought together, inexplicably, at a time when they’re going through very difficult things. Sometimes we can look at those as angels in our lives or we can look at them as adversaries in our lives. In that little bubble of time, I was definitely in a tough spot in my personal life. Neil was in a very tough spot with his physical well-being.

We sat together and talked about that stuff in the parking lot. It got very, very heavy and very, very personal. Neil and I are brothers. This was on a Friday and he said to me, “I gotta go get this procedure on Tuesday. I don’t know if I’ll make it through. This could be the last session that I ever get to do.” And I’m sharing my pain and sorrow with him. He goes, “Would you mind praying for me while I go through this process?” I said, “Dude, are you kidding me? I’m way ahead of you.”

We bonded in a very particularly special way in those few moments. It truly impacted the way that we did our music together from that moment on. I treasure the time that I had with him since that moment. We performed some of the most badass music ever because of the trouble we rose out of, if that makes any sense.

You made Living With War next with Neil in 2006. From what I’ve read, that one was done fast and dirty.

Yeah. We tracked Living With War in a week. That was just another three-piece record.

Did it surprise you he asked you to play on the CSNY tour supporting it?

Well, no. It didn’t surprise me at all. We were the architects of that particular record. When I got called about that, there were some thoughts about who would actually be the rhythm section. You’ve got four guys who all have their opinion about what’s going to be what. As it turned out, I had a conversation about that with Neil. I said, “Look, I’m absolutely into doing this. I want to be the drummer for this tour. I want to be the guy.”

He goes, “You are the guy. Here’s what you gotta do. You and Rick [Rosas] are going to have to go out and hang out with the other three guys. You’re going to have to play with them and they’ll have to sign off on you. They’re going to have to know they’re in good hands.” I said, “That’s no problem. Let’s get it done, get it out of the way.” Then he said something like, “But the bottom line is, this is how it’s going to be, no matter what.” [Laughs]

That really speaks to the group dynamic there. These are four massive artists, each with their own following, but at the end of the day, it’s still Neil’s show.

Yeah. It always has been. Neil always has been the the autonomous one. Not that he doesn’t afford the due respect that those guys deserve. He does. But Neil is such an alpha type guy. There’s just no way that guy is not going to be the director of the traffic. I don’t think he can operate any other way than that.

How was the tour? You’re playing “Let’s Impeach the President” every night when at least half the country didn’t feel that way at all.

For us, it was weird. Before we were allowed to go onto the venue site, they had to have bomb-sniffing dogs from a SWAT team brought into every venue we played at because there were death threats. There were some pretty extreme right points of view about the opinions of these guys and the songs Neil had written.

You’re guilty by association. You’re on deck with these guys singing “Let’s Impeach the President” and you’re in Atlanta, Georgia, which was one of the more memorable nights. You could hear people go, “Fuck you! You piece of shit! Go die!” This was going on between each song. That’s pretty unnerving when you’re strapped to a drum set and you’re basically nothing more than a sitting duck for some nut job that wants to get rid of these guys that want to get rid of the president.

You can pretty much count on the fact that if we’re playing in L.A., we’re good to go. We can pretty much count on the fact that if we’re in Chicago, there won’t be too many problems. But if you’re in Orange County, California, you better be really careful. If we’re playing in Birmingham, Alabama, you better be pretty careful. We experienced all the degrees of that.

The 2008 leg of the Chrome Dreams II tour started with Ralph Molina on drums. When it went to Europe in the summer, suddenly he was gone and you were there. What happened?

I don’t know exactly because I wasn’t there, but some decision was made to make a change. I think there were some musical issues and some business issues, but I really don’t know why. What happened is that I got a call from [Young’s manager] Elliot Roberts. He was one of my favorite people. He was a heavy-duty guy and could be enormously difficult, but I really got along well with him. We always got where we needed to be.

I just got this call. It wasn’t even Neil. It was Elliot. “Hey, what are you doing?” I said, “I’m here in Nashville doing sessions. I’m doing what I’m doing.” He goes, “OK. I need you.” I said, “What’s going on, Elliot?” He goes, “I need you to get on a plane. And I don’t want to negotiate with you. I’m going to give you one number and you’re either going to say yes or no. And then if you say yes, you’re going to get on an airplane, like tomorrow.”

I go, “OK, shoot.” He goes, “Here’s the number.” I went, “Yes.” [Laughs] And that was the end of it. I got on a plane and I met those guys in New York, I think, and then we all got on a charter that flew to Florence, Italy. We did our production rehearsals in Florence. That started my run with him for a couple of more years.

I spoke to Neil on that tour. He told me he loved you guys because you could do Crazy Horse stuff, or Harvest stuff, or whatever he needed at the moment. You guys had so much range.

It was a super cool band. We went deeper into his book than he had ever gone with anyone. It was really fun. We really did a lot of experimentation. We played a lot of very obscure songs.

Right. You’d break out “Time Fades Away” or something he hadn’t done in decades.

Yeah. It was a blast. I got a great story for you. You’re going to love this. When we got to Florence and were in production rehearsals, we were staying in a brand-new Four Seasons that was on the property of some important historical figure that owned the land about 1,000 years ago. We were guinea-pig guests of the Four Seasons before it was officially opened. We had this entire hotel property to ourselves for almost a week.

We were going to the rehearsal studio every day. The second or third day in, Neil calls me and goes, “What are you doing?” I said, “I’m just hanging out in my room.” He goes, “There’s something I want to show you.” I said, “OK.”

I get to his room and I sit down and he puts on “A Day in the Life” by the Beatles on the stereo. He’s looking at me and he’s rocking out to the song. I’m just going, “Yeah. You called me up to listen to the Beatles?” I’m thinking, “What’s going on here?”

He stops the song and goes, “What do you think of this song?” I said, “I think it’s one of the great songs of the Beatles catalog. I’m drawn to the John Lennon side of the Beatles pretty heavily. It’s one of those songs.” He’s looking at me like a 10-year-old and he goes, “Do you think we could do this?” I went, “You want to work up ‘A Day in the Life’?” He goes, “Yeah. Do you think we could do this?” I said, “We have to do this. Just the fact you’re thinking about it means we gotta do it. Let’s start practicing it.”

We rehearsed “A Day in the Life” for probably two weeks at soundcheck before we actually started playing it. When we started playing it, it became this iconic moment in our show. It’s an incredible version of that song. And then the last show of our tour in 2009 that ended at the Hyde Park Calling festival, guess who joined us.

Paul McCartney.

Yep. And he did the middle eight with us. He had never done the song before live. [Ed. note: He actually introduced it into his live set the previous year.] It was the most ultimately bad-ass moment of life for a musician.

To go back a bit, the critics were a little hard on Fork in the Road. I dig some of those songs.

There was some interesting stuff on that. But he was fixed really hard on the LincVolt thing at the time and very, very car-centric, as he’s always been. There was definitely a theme going on with that. You know, what’s cool and what’s not cool is such a subjective thing. That record will probably never compete with Freedom or Harvest or records that are career records, but that’s always been the case with Neil. He’s never been driven by what sells the most records, but what allows him the creative thing that he’s gotta get out, whatever it is.

Look at Trans. That was one of those records that Geffen sued him over. “Why aren’t you making commercial records?” Well, who is to say what that is?

Watching videos of that tour just as a fan now is pretty sad. You see Rick Rosas, Ben Keith, and Pegi Young. They’re all gone. It must be gutting for you.

It’s a really sad thing. A lot of the reason that Neil and I haven’t continued on is because Rick is gone. That prevents that rhythm section from doing what it knew how to do naturally. And I almost think of Ben like a patriarch. He’s such an important figure in Neil’s life as a musician, but also an important part of his life because they were such dear friends. Neil had a very, very tender spot in his heart for Ben. It was just an incredible relationship.

And to have Ben gone and then the divorce with Pegi and then her illness and subsequent death. That’s just, like … wow. It’s a whole lot to process in anyone’s life. It really miss those people. I desperately miss Rick. Of all those folks, Rick and I were the ones that talked every week or two, whether we were doing work or not. We kept in touch.

When Billy [Talbot] got ill and had the stroke [in 2014] before the Crazy Horse tour, Neil called Rick and said, “Can you come in and pinch hit for Billy?” Rick called me to ask me advice about how to work his deal and get him taken care of for that tour.

It’s really hard for me to process all these people that are gone from my life that I miss. And Anthony Crawford, who is one of the other band members, I hardly ever get the chance to talk to him. We weren’t close and he and Neil … the way that tour ended for them wasn’t quite as friendly a thing as what I always enjoyed with them. There’s bittersweet aspects to it all. Rock & roll and bands, that’s what happens. But the loss is kind of heavy. You don’t usually hear about a band like that losing half its members in a relatively short amount of time. That was just really rough.

I miss them. So when Neil and I got on the phone recently, it was such a relief to hear his voice. It was like, “There you are!” That felt good.

I want to end by bouncing around to a few other projects you’ve done. How was your experience with Peter Frampton? I know that was many years of your life.

It was great. We had a great quartet together for about seven years. We became friends and I did quite a bit of recording and touring with him. We did the Live in Detroit DVD that did well with him. Peter is one of the greats.

I think his teen-idol phase caused a lot of people to overlook the fact that he’s a great guitar player and songwriter.

Absolutely. The teen-idol thing overshadowed the fact that he was in Humble Pie and one of the great rock & roll, blues guitar players in the business. It’s a shame, but that’s what happens when you have these giant hit records.

You played on the Beach Boys reunion record in 2012. How was that experience?

That was kind of a modern recording experience. That was myself and a bass player named Michael Rhodes. We were overdubbing to existing tracks on that record. It wasn’t like we were all together in the room with Brian [Wilson]. They had already cut fundamental tracks and the producer of that record brought us in to overdub to the songs.

You’re also on Jessica Simpson’s In This Skin.

[Laughs] Man! Wow! That was a lefthand turn! That was just one of those sessions. It was kind of funny. What I remember was that I was going into the session and she was on her phone gossiping with somebody about something and she was on her way out the door. I was working with Keith Thomas, the producer, on getting the drum tracks done for her record. But she was kind of not involved in the music at all, not in my experience anyway.

You’ve done a ton of country records. I imagine they work very differently from rock records in most cases and are much more efficient.

Yes. Very, very efficient, very systematic, most of the time. Most of the players are upper-five-percentile–level players. It’s a different kind of animal and incredibly rewarding. Contrary to that, the record I did with Alison Krauss, Windy City, that record was amazingly creative and not Nashville punch-the-number, bang-bang-bang kind of thing. That record was a great record, man. If you haven’t heard it, I highly recommend it.

Then you’ve worked with Bob Seger and Stevie Nicks. Your list of credits is just so absurdly long. All the Kenny Chesney stuff, too.

Yeah. A month or two ago, we just went in and recorded a lot more new music. The Kenny stuff is a little more in line with the stereotypical methods that are used here, but Stevie’s record was produced by Dave [Stewart]. That wasn’t typical Nashville stuff. That was Nashville players, but we didn’t track it like a Nashville record. We did it the way that Stevie wanted to do it.

You really seem like you’ve been busier in the past 10 years than any other time in your career.

Honestly, man, since 1993, I’ve had an unbelievable recording career here. The last eight to 10 years have been amazing, but it’s starting to get more diversified now. I’m starting to produce more. I don’t want to say I’m getting older. That’s making myself a dinosaur, but I’m a generation ahead now of the new, young crop coming out and everyone is due a time at the wheel. I really love working on the records that I get called to play on. I love the fact that people still regard me as a contemporary and still viable. That means a lot to me. I work really hard at staying that way.

I also work really, really hard at being unpredictable. I don’t want to just do one thing. I did my last tour with Joe Walsh a couple of years back. Then I settled into my life in Nashville. It’s illogical to people that look at guys like us and always say, “You can’t leave a session gig that lucrative. If you leave, you’re going to lose all your accounts.” But my career has never been driven by that. The art and the music is what drives me to decide what to do. That’s always what has driven me.

Source: Read Full Article