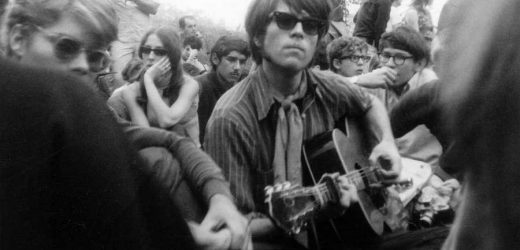

Even in the Sixties, Eric Andersen was never a typical troubadour. Harper’s once described him as sporting “high cheekbones like Rudolf Nureyev’s,” and he eschewed folk sing-alongs for his own sensuous ballads, like “Violets of Dawn,” “Thirsty Boots,” and “Close the Door Gently When You Go.” The Beatles’ Brian Epstein wanted to manage him, Johnny Cash invited Andersen onto his network TV series, and Andersen’s friend Joni Mitchell guested on Blue River, the stately 1972 album that became the singer-songwriter’s commercial breakthrough. Andersen was even cast in one of Andy Warhol’s earliest movies, 1965’s Space.

Yet for whatever reasons and misfortunes, Andersen never hit the stratosphere in the same way as so many of his contemporaries. Epstein died right before he planned to take Andersen on, and the tapes for Stages, the follow-up to Blue River, went mysteriously missing, derailing his career (they weren’t found until nearly 20 years later, when they were finally released). In the Eighties, Andersen moved to Norway, where he lived for more than 20 years, and continued releasing strong albums like Ghosts Upon the Road and You Can’t Relive the Past, some of which included co-writes with his friend Lou Reed.

But a reassessment of Andersen’s work and contributions seems to be underway. The Songpoet, a new documentary on his life, directed by Paul Lamont, begins airing on PBS stations around the country this week, and can also be viewed online. An in-the-works tribute album will include newly recorded covers of Andersen songs by Jackson Browne, Amy Helm, Scarlet Rivera, and others, as well as previously released renditions by Bob Dylan, Linda Ronstadt, and Rick Nelson. A new album, Dance of Love and Death, is nearing completion.

Andersen, 78, spoke to RS from his current home in the Netherlands, where he’s lived for 15 years with his wife, singer-songwriter and social-sciences writer and researcher Inge Andersen. “These are just my impressions,” he warns of discussing the doc. “I can’t give you, like, stock answers about how it is to see a film.”

So what was it like watching the first documentary ever made on your life?

In the theater, I’m sitting there drinking Coca-Cola and eating popcorn, munching away like everybody else, looking at this guy, this life. It was a pretty surprising thing. You can’t see yourself when you’re going out about your business, walking around the streets and doing what you got to do. You look in the mirror, shave, brush your teeth. You’re always seeing things from the inside looking out. So I was looking at this like anybody else. Here’s a guy walking around doing things. It’s me, supposedly, when I was living and doing those things. It’s hard to believe.

We know you as a solo performer, but your career actually started in a college band called the Cradlers, right?

That was my first professional group, me and his guy from college. It didn’t last too long, but we opened up for the Kingston Trio and Peter, Paul, and Mary. That was my first taste of the bright lights.

And then, after a trip to San Francisco, you eventually wound up in New York and became part of that music scene.

My real college education was sitting at the feet of all the blues guys. I did an album for Vanguard [in 1964], but they took almost a year and half to put it out. I had nothing to do. No money. I was living at [the Sixties folk music publication] Broadside magazine for a while, or living off Tompkins Square Park, cooking for junkies — a young couple from Westchester — who had the money to hire somebody to cook for them. I was doing these odd jobs. Every night I’d go down to the Gaslight or wherever, and I got into these places for free. In those days, everybody played six nights, including Miles Davis, John Coltrane, and Mingus. Or Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Fred McDowell. Every single night for weeks. It happened to coincide with the advent of the long-playing record, which is crucial because Miles or Coltrane could take long solos. Bob Dylan could write “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall.” Suddenly you could stretch out.

In the film, Warhol friend Danny Fields says he saw you on the street and was struck by your looks and then brought you and Warhol together.

I didn’t realize until Danny talked about it in the movie that Andy was in a little bit of a little swoon: “Oh, God, he made a record?” I guess to most people, somebody who made a record was a big deal. So I went up to the Factory and became friends with Andy. We had this connection, both of us being from Pittsburgh. I never was intimidated by him; I just liked him a lot. I’d go up and watch him paint sometimes. He bootlegged a show of mine at the Gaslight.

He once gave me a beautiful painting and signed it. I asked him if I could sell it for a house, and he said if it’s for a house, that would be great, so OK. I sold it dirt cheap to a German buyer. Fast forward, years later, I open The New York Times and there’s a full-page ad with my fucking painting for sale for something like $12.5 million. Lou Reed was always teasing me: “Tell me about the Warhol painting.” I finally had to say, “Can you please not bring this up in front of people?”

All those years, I had never met Lou. We both knew Andy but I never met Lou, never ran into him. I saw him a couple of times with the Velvet Underground. It’s funny — you think, me and him, how does that figure? But he ended being my best friend in New York.

How did you end up acting in Space?

Andy usually rolled the film and walked away and painted, or something, but this time he was behind the camera. My legs were splayed and I’m playing the guitar. I learned my lines. I was trying to be cooperative. When it came out, I went to a theater and I’m seeing this zoom shot on my crotch. I’m in my Navy peacoat sinking low in my seat, saying, “Holy fuck, I gotta get out of here.” I was so embarrassed. I thought it was such a cinematic disaster. It actually works in a way. But at the time I didn’t see it.

Your story does seem to include a lot of missed opportunities. Certainly Stages is a major one. In the doc, we hear some conjecture that someone at Columbia Records intentionally misplaced the tapes. What’s your theory?

Well, somebody lost them on purpose. They weren’t gone when I left Nashville to run up and do a tour with Harry Chapin. Then I get a call and somebody tells me, “Oops, sorry, your tapes got lost.” Yeah, right.

Do you think you were difficult at the time, as the film also suggests?

I don’t think that’s true at all. That’s an easy story. When the tapes disappeared, remember this: Clive Davis got fired. Clive was my man. He brought me on and he was running the show. So my protection was gone. And these people wanted to keep their jobs. So here I am, you know — just little naive me. I smelled a rat, of course, and I knew they couldn’t have been lost. But what can you do? Instantaneously and unwittingly, not through will or a life choice, you instantly become a Buddhist — because if you get attached to this, it will destroy you. Even though it’s your work.

Looking back, which was tougher to handle — that situation or Brian Epstein’s death?

Between those two is a tough call. They both hurt, of course, because Brian was ready to go. He never hassled me. He loved Debbie [Green, Andersen’s girlfriend and later wife]. It was a family feeling. He said to me once, “Look, just do what you want to do. Don’t change anything. I’ll just take what you do and put it in certain places.”

What did he mean by that?

Who knows? Like maybe open a show for the Beatles or something? He tried like hell to get me onto Monterey [Pop], but they’d already booked it up. I went to some Beatles sessions, too. You know, eating hashish under the table from John Lennon and drinking Coca-Cola.

From Epstein’s letters to you, which we see in the movie, it also seems like he was getting into the folk and singer-songwriter world right before he died.

Yeah, he smelled something. He thought there was something to the narrative, the person with a guitar who can tell a story Like telling people a bedtime story.

How did you end up performing on Johnny Cash’s network TV show?

Kris Kristofferson got me on that show. We were in the Troubadour in L.A. and he just came up to me at the bar and said he loved my song “Come to My Bedside, My Darlin’.” It’s a song that really hit people like Kris and Jerry Garcia. It had this innocent beauty about it, or something. The Brothers Four recorded it and it got banned. The singles all got returned or thrown out. It was sexual, mentioned the word “bed” and stuff. But Kris came up to me and said, “I love that song.” It informed some of his things, like “Help Me Make It Through the Night.” He talked to John [Cash] about the show.

The weird thing is, I did a song on the show called “Born Again.” It was about waking up and having a fresh start. Little did I know that this born-again movement was a new thing, the evangelical religious movement, and I write this song having no clue about it, and they’re all crazy about the song. Later I go to John’s house, we’re having dinner and hanging out, and June explained this whole thing to me. I didn’t have any idea why they were going crazy for it. If I didn’t get my Mercedes-Benz with the Brothers Four, I might have had a crack at it with the Christians. They love money.

People also forget that you were aboard the Festival Express train tour of Canada, alongside the Dead, the Band, Janis Joplin, and many others.

It was one big hotel lobby on tracks, with places to sleep and a bar car. They had, I think, four doctors on board to administer pharmaceuticals, to sober people up for the shows. It was a wild and beautiful and incredible thing. There was a country music car, and a blues car with Buddy Guy. Garcia was there jumping back and forth.

Janis and I became very close friends. When Debbie and I had a new baby, Janis called to tell me Jimi Hendrix had just died in London. She was telling me how she had warned him about doing drugs and be careful with that. [Pause] OK. Two weeks later, I’m in Venice, California, walking to the little local liquor store. And that’s when there were boxes in the street where you could put in a quarter and get a newspaper. And all the papers say, “Rock Star, Janis Joplin, Dead at 27.” That’s how I found out. It was extremely difficult to deal with. The music business isn’t especially conducive to good health.

The movie also reminds us that you had a relationship with Patti Smith in the early Seventies. How did you meet?

I was living at the Chelsea Hotel, and I think I met her through Bobby Neuwirth or Gregory Corso. And we became friends. Sam Shepard was living there once in a while too. She loved Keith Richards’ haircut and she loved Jim Morrison. She loved all these kinds of people. But she was straight as an arrow, you know. She didn’t drink or smoke or anything. it was all brain chemistry. I took her once up to Canada to meet Irving Layton, a great poet. I haven’t seen Patti in a long time. We were pen pals for a while.

Is “Wild Crow Blues” (“She’s just like me with a street-kid mouth and makes love just like Rimbaud”) about her?

Yeah. I mean, the songs have to come from somewhere.

When I heard Dylan’s “Murder Most Foul,” I couldn’t help but think of “Beat Avenue,” the title cut from your 2003 album [a 26-minute, Beat-inspired epic based around JFK’s assassination].

Bob had that album. He knew all about it. He says it’s the folk process.

Are you still in touch with Joni?

Yeah. She’s the godmother of my oldest daughter. She’s recovering slowly. She has a lot of help. She comes to all my shows when I go to L.A. She comes in and all the people who help her and work with her, they take up a whole row!

Thirty years ago this week you performed at a Tim Buckley tribute concert in Brooklyn. Did you meet his son Jeff, who sang that night as well?

Yeah. I don’t think anybody introduced me to Jeff. I don’t even know his singing voice. I’m sitting there just by myself, and Jeff comes up and pulls up a chair right in front of me. He wanted to know everything I could remember about his dad, from the Village or having coffee with him or talking to him or just any crumbs. And it was so beautiful, so poignant and touching, to see a kid try to be close to his dad.

Hal Willner [the producer who died of complications from the coronavirus last year] was there. That was a heavy loss too. We were supposed to do a one-man show in New York on Lord Byron. The question isn’t: Why do we lose people, why do people die? The real question is: Why are we still here? And what are we doing with it?

How did you survive it all when friends and collaborators like Janis, Lou Reed, Townes Van Zandt, and Rick Danko have passed?

Sometimes you have a question; it doesn’t always have an answer. My wife Inge says you’re put on Earth to finish the things you were supposed to finish. And I know with me, in my case, it’s music and writing. I know there are things that are not finished yet. So, you know, we hang in there till to accomplish the things we were planning to do.

Source: Read Full Article