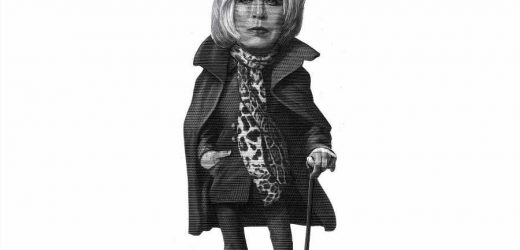

Marianne Faithfull has lived several lifetimes in her 74 years. She was only 17 when the pop song “As Tears Go By” turned her into a star overnight in 1964, and she was in her early twenties when her relationship with Mick Jagger made her a tabloid lightning rod. After that ended, she fell deep into drugs, living for a while on the streets, before making a stunning comeback in 1979 with Broken English, an album of dark-hued, New Wave–influenced music that complemented the way her voice had grown deeper and more profound. She acted in theater and films and reinvented herself as a jazz chanteuse and dream-pop singer, all before issuing her page-turner of a memoir, Faithfull, in 1994. But nearly 30 years have passed since then, during which time she’s teamed with songwriters like PJ Harvey, Nick Cave, and Mark Lanegan for albums that have comprised her so-far unimpeachable third act.

Related Stories

Marianne Faithfull Bares Her Poetic Soul on 'She Walks in Beauty'

Hear Marianne Faithfull Tenderly Read Lord Byron's Romantic Poem 'She Walks in Beauty'

Related Stories

The Private Lives of Liza Minnelli (The Rainbow Ends Here)

The 100 Greatest Motown Songs

Considering all the ways she’s redefined herself over the years, it’s no surprise that her latest record represents yet another new avenue for Faithfull. A collaboration with violinist and songwriter Warren Ellis, She Walks in Beauty finds Faithfull reciting poetry by England’s great romantic poets: Lord Byron, John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and William Wordsworth. Her voice, which is still warm and rich, adds rare depth to those artists’ words, and the record’s ambient music — performed by Ellis, Cave, Brian Eno, cellist Vincent Ségal, and producer-engineer Head — only heightens the words. Whether capturing the might of an Egyptian monument in Shelley’s “Ozymandias” or comparing a bird’s beauty to a place “where men sit and hear each other groan” in Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” she speaks the words in a way that conveys her experience.

When Faithfull spoke with Rolling Stone for the Last Word interview, that same sense of resolve came through the phone line. Although she was still recovering from a scary experience with Covid-19 from last year, she still spoke passionately and wittily about her philosophies and experiences, and the lessons she’s learned over the years.

You survived a lengthy bout with Covid last year. How are you feeling now?

It’s terrible. I got long-term Covid, where you get better from the virus, but you have leftover [symptoms]. Apparently, they now think that you do get better from long-term Covid; it’s not forever. That is good.

On your new album, you recite poetry by Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, and many others. What makes a good poem?

There are certain technical aspects that I really enjoy, like alliteration and really good rhyming. I think a really good poem has a rhythm to it. Like music, choice of words is very important. It’s quite a big thing, a great poem.

John Keats wrote, “Beauty is truth, truth beauty — that is all/Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.” What do those words mean to you?

I keep that phrase right up there in my life, in my mind. They’re both quite hard to reach, but you can do it. You can try anyway.

You became famous when you were a teenager. What’s the best part of success and what’s the worst?

The best part is that some people start to appreciate and like your work. The worst part is fame, isn’t it? I think fame is pretty awful. The really, really famous people that everybody loves, they die — like Princess Diana. That’s a very extreme example of what fame can do. And there’s this awful thing I’ve been watching about poor little Britney Spears. Christ. Luckily, I’ve never been quite that famous or that grand, and certainly not that rich. And anyway, [my fame] was only for quite a short time. The rest of it has been solid, plugging hard work.

You wrote in your memoir that the law of pop music is that you have to give yourself away to get anything. Was anyone ever exempt?

Really, only a couple made so much money that they didn’t get ripped off. The Beatles, the Stones, but both of them had moments where they were being ripped off. Let’s not think about that, for God’s sake.

Who are your heroes and why?

Well, of course my great hero of all time is Shakespeare. I think he’s the most wonderful writer ever. And then Oscar Wilde. The great socialists in the world, Beatrice Webb. There are great Americans, too, like Edgar Allan Poe. Then there’s Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley. Napoleon is a bit of a hero.

He’s a bit controversial, though.

Yeah, but I think he’s pretty heroic, and the Duke of Wellington [who defeated Napoleon], too. They’re both heroic really. I think Churchill was a bit of a hero; when they really needed him, he was there.

What was your favorite book when you were a kid? And what does that say about you?

I don’t know what it says about me. I loved all the Narnia books — The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, all that. They’re wonderful. As I’m half-Austrian, I also grew up with Der Struwwelpeter and all that. I thought they were rather wonderful. And then there’s Hilaire Belloc, who wrote these wonderful poems called Cautionary Tales. Would you like to hear one? “There was a boy. His name was Jim. His friends were very good to him. They gave him tea and cakes and jam and slices of delicious ham and even took him to the zoo, which was where the dreadful fate befelled him, which I now relate. … “

What is your favorite book?

Actually I’m reading one that I really love at the moment, Miles Davis’ autobiography [Miles]. It’s brilliant. It’s really funny because it’s very dishonest in a way; the way he talks about other people with heroin problems compared to him is hysterical. [He makes it sound like] he was really good and didn’t really have a problem, but this other guy was terrible [laughs].

You managed to beat your heroin addiction decades ago. What did you learn from that time in your life?

I just wish I’d never touched any of that stuff, and cigarettes and even alcohol — actually all of it. I’d be a lot better now.

You’ve recorded your first hit, “As Tears Go By,” three times in your career — first when you were 17, then at 40, and most recently when you were 71. What age is the best for singing that song?

I liked the last one, the one I did on [2018’s] Negative Capability, best. It took me a long time to really get it. I thought the first one was just too bright and breezy and poppy, and the second one was too sad, and the third one is really balanced.

It’s interesting that a song that you sang as a teenager takes on more significance with time.

As you grow up, yes, of course it does. It was a very weird thing to do, to give me that song to sing when I was only 17. Both Mick [Jagger] and Keith [Richards] were 21 or 22 when they wrote it, but they are very brilliant.

How did dating Mick around that time make you a stronger woman?

I don’t know if it did. It almost destroyed me. Although it was wonderful, it was only four years. It was a wonderful time, and he was great, but I don’t think I fit into that life or what he wanted in a woman, that’s all. I couldn’t do it.

What did you learn from Rolling Stones manager Andrew Oldham all those years ago?

Oh, God, not much. He obviously gave me something, I suppose; it was through Andrew Oldham that I met Mick and Keith.

You wrote about how he misrepresented your character and turned you into this rich aristocratic kid, which wasn’t you at all.

Oh, yeah. I was “the angel with big tits.” Thanks a lot, man.

You’ve collaborated with so many wonderful people over the years — Hal Willner, Warren Ellis, Nick Cave —

Let’s take a moment to talk about Hal Willner. How am I going to live on this planet without Hal Willner? How is anybody? I wish he was alive. I wish he could hear this beautiful record I’ve made. I wouldn’t have been able to do it without years and years and years of friendship and love of Hal. Actually, my grandson — Oscar, my Oscar — is making a little film about him. I think it will be lovely.

What makes a good collaborator for you?

I really don’t know. It’s got to be someone where we both give to each other. Warren Ellis is just such a genius and Nick, too. What Warren did with the poetry is wonderful. The music, the piano that Nick put on, the work that Brian Eno did, Vincent Ségal, who plays cello, is just wonderful.

You’ve lived in London, Paris, New York, Ireland. What makes you feel like you’re at home?

I am at home on the planet. At least I have felt at home on the planet up ’til now. I did love Paris I must say. But my son really wanted me to come back to London. I think he deserved it. Of all the people I love in my life, and I love Nicholas very much, I think he got the least of me. He has every right to ask me to give him more and I want to. It’s not easy because we haven’t really spent that much time together. We’re making up for lost time. It’s hard work but we do love each other. I guess human relationships are difficult, aren’t they?

What do you feel younger generations could learn from yours?

I would say, ideally, to be kind to yourself and compassionate to yourself and others. Don’t judge yourself too harshly. If you can, stay in the moment. That’s what I did. I mean that gets harder, of course, as you get older, but I still try.

Source: Read Full Article