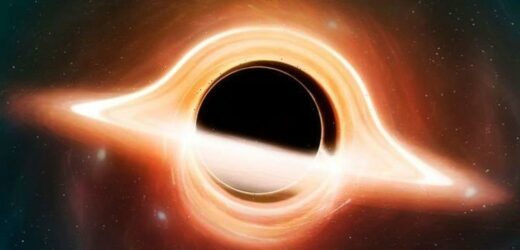

Black hole appears to eat neutron stars ‘like Pac-Man’

We use your sign-up to provide content in ways you’ve consented to and to improve our understanding of you. This may include adverts from us and 3rd parties based on our understanding. You can unsubscribe at any time. More info

American astronomer Edwin Hubble was the first to observe in the Twenties that galaxies are racing away from us, and the farther away they are, the faster they appear to be moving. The groundbreaking discovery confirmed that the universe is expanding, although scientists have so far been unable to explain exactly why this happens. A team of international researchers from across the US has now made an astonishing discovery based on the work laid down by Hubble 100 years ago.

According to the principles of Albert Einstein’s 1915 general theory of relativity, black holes can merge with one another and in the process swell in size.

Astronomers confirmed these theoretical predictions in 2015 with the world’s first detection of gravitational waves caused by black hole collisions.

But there is a problem – many of the black holes scientists have detected across the cosmos appear to be much, much bigger than expected.

Researchers at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, the University of Chicago, and the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor believe they may have found a solution to the cosmic conundrum.

In a new paper published this month in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, scientists have proposed black holes can grow more massive as a result of the universe expanding.

Although black holes absorb all light and cannot be seen by the naked eye – hence the term “black” – astronomers can still detect the effect they have on space.

The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO), for instance, detected in 2015 the gravitational shockwave created when two black holes merged – ripples in the very fabric of time and space that reached the Earth from billions of light-years away.

Physicists originally predicted the black holes would have a mass less than about 40 times our Sun.

This is because merging black holes are believed to originate from massive black holes that struggle to stay together if they grow too big.

But the LIGO and Virgo observations have detected many black holes masses 50 to 100 times of our Sun.

The new study now suggests the expanding universe is causing black holes to grow bigger, in an unusual twist of events.

Black hole: Brian Cox says we 'know nothing' about the centre

This is a disturbing theory because the expanding universe does not cause galaxies and stars to grow bigger, but rather expands the fabric of the universe itself.

In other words, the space between planets and stars and galaxies is growing like the surface of a balloon that is being inflated.

The University of Hawai’i researchers modelled the size of black holes in an expanding universe – something astronomers typically avoid.

Kevin Croker, a professor at the UH Mānoa Department of Physics and Astronomy, said: “It’s an assumption that simplifies Einstein’s equations because a universe that doesn’t grow has much less to keep track of.

“There is a trade-off though: predictions may only be reasonable for a limited amount of time.”

The expert and his colleagues have proposed that a black hole’s size is proportional to the size of the universe but raised to some exponent.

Consequently, the mass of a black hole will grow in an expanding universe, and if the expansion is accelerating – because of a mystery force called dark energy – then black holes should also grow at an increasingly faster rate.

Gregory Tarlé, research co-author and professor at the University of Michigan, said: “I have to say I didn’t know what to think at first.

“It was such a simple idea, I was surprised it worked so well.”

Although just a theory at this stage, the researchers believe their findings fit well with our present understanding of the universe.

The model does not clash with our models of how stars are born, evolve and die.

However, the researchers stressed that the mystery of LIGO and Virgo’s colossal black holes is far from being solved.

Michael Zevin, co-author and NASA Hubble Fellow, said: “Many aspects of merging black holes are not known in detail, such as the dominant formation environments and the intricate physical processes that persist throughout their lives.

“While we used a simulated stellar population that reflects the data we currently have, there’s a lot of wiggle room.

“We can see that cosmological coupling is a useful idea, but we can’t yet measure the strength of this coupling.”

Source: Read Full Article