Professional footballers who play in defence are FIVE times more likely to develop dementia – while goalkeepers are the least likely to be affected by the neurodegenerative condition

- Dementia is five times more likely in professional footballers who play in defence

- Study previously found ex-players are three times more likely to die of condition

- Neurodegenerative disease risk varies by position and career length, but not era

- Football Association and Professional Footballers’ Association welcome findings

Professional footballers who play in defence are five times more likely to develop dementia than people in the general population, new research has found.

Defenders suffer repeated blows to their head, mainly through heading leather footballs and colliding with other players.

However, goalkeepers are no more likely to develop the neurodegenerative condition than members of the general population, according to the study.

Researchers said the risk varies by position and career length, but not by the era in which they played.

The new findings also show that neurodegenerative disease diagnoses increased based on the length of a career, with a five-fold increase in those with the longest careers (defined as more than 15 years).

Scroll down for video

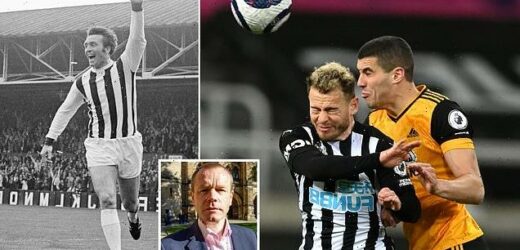

Professional footballers who play in defence are five times more likely to develop dementia than midfielders, strikers and goalkeepers, new research has found. Pictured: Conor Coady (left) and Ryan Fraser (right), jumping for a header

Defenders are five times more likely to develop dementia

Neuropathologist Prof Willie Stewart, has previously established that former professional footballers are three-and-a-half times more likely to die of neurodegenerative diseases than the general public.

Now he and his team have found that defenders are five times more likely to develop dementia, while the longer a player’s career the bigger their risk of neurodegenerative disease is.

However, the era in which a footballer played — whether that be the 1930s, 60s, 70s or late 90s — had no bearing on the risk.

Goalkeepers had a similar risk of dementia as the general population, but for outfield players the risk was almost four times higher.

Experts at the University of Glasgow have been investigating fears that heading the ball could be linked to brain injuries.

The long-awaited study, commissioned by the Football Association (FA) and Professional Footballers’ Association (PFA), began in January 2018 after claims that former West Brom striker Jeff Astle died because of repeated head trauma.

It has compared the deaths of 7,676 ex-players — all of whom were born between 1900 and 1976 and played professional football in Scotland — to 23,000 from the general population.

Researchers led by consultant neuropathologist Prof Willie Stewart also wanted to know whether the risk of neurodegenerative disease varied by player position, length of career or playing era.

The results showed that goalkeepers had a similar risk to the general population of developing dementia.

However, the risk for outfield players was almost four times higher and varied by player position, with risk highest among defenders — around five-fold higher.

The new findings also show that neurodegenerative disease diagnoses increased based on the length of a career, ranging from a doubling of risk in those with the shortest to around a 5-fold increase in those with the longest careers (defined as more than 15 years).

However, despite changes in football technology and head injury management over the decades, there is no evidence of a difference in risk between those who played in the 1930s, 60s and 70s — with rain-sodden, heavy-leather footballs — and the late 90s.

Although balls are lighter today, they now travel more quickly – up to 80mph in the professional game – and as a result can cause even more damage.

Prof Stewart said: ‘We have already established that former professional footballers are at a much greater risk of death from dementia and other neurodegenerative disorders than expected.

‘These latest data take that observation further and suggest this risk reflects cumulative exposure to factors associated with outfield positions.’

The long-awaited study began in January 2018 after claims that former West Brom striker Jeff Astle (pictured above) died because of repeated head trauma

Prof Willie Stewart (pictured left), a neuropathologist from the University of Glasgow arranged for an analysis of Jeff Astle’s (right) brain

HOW CAN PLAYING FOOTBALL LEAD TO DEMENTIA?

Footballers suffer repeated blows to their head, mainly through heading leather footballs and colliding with other players.

Leading scientists have found such injuries can lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a crippling condition which can cause dementia.

Former England and West Bromwich Albion striker Jeff Astle died in 2002, aged 59, from CTE. He was left unable to recognise his own children.

An inquest ruled that Astle’s CTE was caused by heading footballs – the first British professional footballer to be officially confirmed to have done so.

Three of the nine surviving members of England’s 1966 winning World Cup team have Alzheimer’s – Martin Peters, Nobby Stiles and Ray Wilson.

Stiles’ son two years ago criticised the FA for failing to properly investigate a link between the sport and degenerative brain disease.

A landmark study of 14 retired footballers by University College London experts in 2017 found four had a condition CTE.

The link between head trauma and CTE is widely established in boxing, rugby and American football, where such injuries are common.

Former New England Patriots star Aaron Hernandez had CTE when he killed himself in April at the age of 27 while serving a life sentence for murder.

In separate research led by Prof Stewart, a specific pathology linked to brain injury exposure, known as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), has been described in a high number of the brains of former contact sport athletes, including ex-amateur and professional footballers.

Prof Stewart added: ‘The evidence is clear that the standout risk factor for neurodegenerative disease in football is exposure to head injury and head impacts.

‘As such, a precautionary principle approach should be adopted to reduce, if not eliminate exposure to unnecessary head impacts and better manage head injuries in football and other sports.’

The FA welcomed the new findings and said it was enabling football’s governing body to ‘make changes in the game’.

Maheta Molango, chief executive of the PFA, the players’ union, said: ‘The welfare of our players, past, present and future is at the forefront of everything we do and this data will inform us how best to protect them and improve our services.’

The research, funded by the FA and PFA, previously showed that former players are three-and-a-half times more likely to die of dementia than people of the same age range in the general population.

It also found a five-fold increase in the risk of Alzheimer’s, a four-fold increase in motor neurone disease and a two-fold increase in Parkinson’s.

However, ex-players were less likely to die of other common diseases, such as heart disease and some cancers, the research said.

The latest research comes just days after English football announced restrictions on heading among adults for the first time, with professional players now limited to 10 ‘higher-force’ headers per training week.

Guidelines will apply from the Premier League to grassroots from the start of the 2021-22 season. Primary school children are already banned from practising heading completely.

The new guidance also recommends that clubs develop player profiles that consider gender, age, playing position, the number of headers per match and the nature of the headers.

At least five of England’s 1966 heroes, including Sir Bobby Charlton, have lived with dementia

And clubs are expected to work closely with players to ensure they have time to recover from a match before being asked to head the ball in training.

It is not uncommon for some players to head the ball between 10 and 20 times in a top-flight game.

Meanwhile, amateur players are being told to only head the ball 10 times a session with only one session a week where heading is practised.

The new research titled ‘Association of field position and career length with neurodegenerative disease risk in former professional soccer players’ is published in the journal JAMA Neurology.

HOW DID ENGLAND STRIKER JEFF ASTLE DIE? INQUEST REVEALS HE SUFFERED CTE FROM HEADING LEATHER FOOTBALLS

Former England and West Bromwich Albion striker Jeff Astle died in 2002

Former England and West Bromwich Albion striker Jeff Astle (right) died in 2002.

He was only 59 but doctors said he had the brain of a 90-year-old after suffering from chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).

CTE is a progressive, degenerative brain disease found in individuals with a history of head injury, often as a result of multiple concussions.

An inquest ruled Astle died from dementia caused by heading footballs – the first British professional footballer to be officially confirmed to have done so.

Astle, who was left unable to recognise his own children, once commented that heading a football was like heading ‘a bag of bricks’.

His family set up the Jeff Astle Foundation in 2015 in order to raise awareness of brain injury in sport. His daughter Dawn said ‘the game that he lived for killed him’.

Danny Blanchflower, who captained Tottenham Hotspur during their double winning season of 1961, died after suffering from Alzheimer’s disease in 1993. He was 67.

His death has also been linked to heading the heavy, leather balls of the 1940s and 50s, along with fellow Tottenham players Dave Mackay, Peter Baker and Ron Henry.

Source: Read Full Article