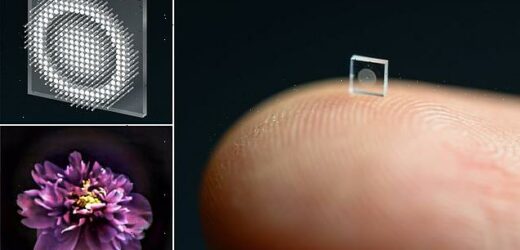

Say cheese! Microscopic camera the size of a grain of SALT is developed that can produce crisp, full-colour images ‘on par with lenses 500,000 times larger’

- The camera is a mere half a millimetre across and made from a glass-like material

- It has a ‘metasurface’ covered with 1.6 million tiny, cylindrical optical antennae

- AI-based algorithms convert each post’s interaction with light into an image

- The camera could find applications in tiny robots and for medical imaging

Despite being the size of a grain of salt, a new microscopic camera can capture crisp, full-colour images on par with normal lenses that are 500,000 times larger.

The ultra-compact optical device was developed by a team of researchers from Princeton University and the University of Washington.

It overcomes problems with previous micro-sized camera designs, which have tended to take only distorted and fuzzy images with very limited fields of view.

The new camera could allow super-small robots to sense their surroundings, or even help doctors see problems within the human body.

Despite being the size of a grain of salt, a new microscopic camera design can capture crisp, full-colour images on par with lenses 500,000 times larger. Pictured: the tiny camera

MAKING THE CAMERA

The so-called metasurface, which allows the camera to capture quality images even though it is so small, was fabricated by University of Washington optical engineer James Whitehead.

They are made of silicon nitride, a glass-like material which is, usefully, compatible with the semiconductor manufacturing methods presently used to produce computer chips.

This, the researchers explained, means that — once a fitting metasurface has been designed — it could be easily mass produced for lower costs than the lenses used in normal cameras.

Within a traditional, full-sized camera, a series of curved glass or plastic lenses serve to bend incoming light rays into focus in a piece of film or a digital sensor.

In contrast, the tiny camera developed by computer scientist Ethan Tseng and his colleagues relies on a special ‘metasurface’ studded with 1.6 million cylindrical posts — each the size of a single HIV virus — which can modulate the behaviour of light.

Each of the posts on the 0.5-millimetre-wide surface has a unique shape that allows it to operate, in essence, like an antenna that can shape an optical wavefront.

According to the researchers, the key to the camera’s success came in the integrated design of the optical metasurface and the machine-learning based signal processing algorithms that interpret the post’s interaction with light into an image.

The photographs that the tiny device takes offer the highest-quality images with the widest field of view for any full-colour metasurface camera developed to date.

Previous designs have tended to be beset by major image distortions, restricted fields of view and problems capturing the full spectrum of visible light.

Experts refer to the latter as ‘RGB’ imaging, because it relies on the mixing of the primary colours of red, green and blue to make other colours – just like the mixing of red, yellow and blue paints in primary school.

Aside from a little blurring near the edges of the frame, the images the tiny camera can capture are comparable to those taken with a regular, full-sized camera setup featuring a series of six refractive lenses.

The camera is also able to function well in natural light, rather than the pure laser light or other highly idealised conditions required by previous metasurface cameras if they were to produce good-quality images.

It overcomes problems with previous micro-sized camera designs, which have tended to take only distorted and fuzzy images with very limited fields of view. Pictured: images of a flower, taken with the previous state-of-the-art microscopic camera (left) and the new design (right)

‘It’s been a challenge to design and configure these little microstructures to do what you want,’ said Mr Tseng, who is based at Princeton University in New Jersey.

‘For this specific task of capturing large field of view RGB images, it’s challenging because there are millions of these little microstructures [on the metasurface], and it’s not clear how to design them in an optimal way.’

To overcome this, University of Washington optics expert Shane Colburn created a digital model that could simulate metasurface designs and their photographic output, allowing automated testing of different nano-antennae configurations.

According to Professor Colburn, the sheer number of antennae on each surface and the complexity of their interactions with light meant that each simulation used ‘massive amounts of memory and time.’

Aside from a little blurring near the edges of the frame, the images the tiny camera can capture (left) are comparable to those taken with a regular, full-sized camera setup (right) featuring a series of six refractive lenses.

‘Although the approach to optical design is not new, this is the first system that uses a surface optical technology in the front end and neural-based processing in the back,’ said optical engineer Joseph Mait, who was not involved in the study.

‘To jointly design the size, shape and location of the metasurface’s million features and the parameters of the post-detection processing to achieve the desired imaging performance,’ Mr Mait added, was a ‘Herculean task’.

The team is now working to add computational abilities to the camera — both to further enhance image quality, but also to incorporate things like object detection that would be useful for practical applications.

APPLICATIONS OF THE CAMERA

Pictured: The tiny camera relies on a special ‘metasurface’ studded with posts which can modulate the behaviour of light

According to the researchers, the camera would be ideal for use in small-scale robots, where size and weight constraints can make traditional cameras difficult to implement.

The optical metasurface could also be used to improve minimally-invasive endoscopic devices — allowing doctors to better see inside of patients in order to diagnose and treat diseases.

Furthermore, envisages paper author and Princeton University computer scientist Felix Heide, the concept could be used to turn surfaces into sensors.

This, he said, ‘could turn individual surfaces into cameras that have ultra-high resolution, so you wouldn’t need three cameras on the back of your phone anymore, but the whole back of your phone would become one giant camera.

‘We can think of completely different ways to build devices in the future.’

Source: Read Full Article