Chicago then and now: Captivating book matches vintage snapshots of the city with modern photos captured from the same angle

- Chicago Then and Now, written by Kathleen Maguire, sets out ‘to tell the story of the city’s rich history’

- ‘The evocative photos on these pages reflect the many faces of Chicago’s heritage,’ reads the introduction

- Locations that feature in the tome include the Art Institute of Chicago and the Michigan Avenue Bridge

‘I’ve watched my city falter and prosper, crumble and rebuild, lurch forward and regress.’

So writes native Chicagoan Kathleen Maguire in the introduction to Chicago Then and Now, published by Pavilion, a book that chronicles Chicago’s fascinating transformation over the past century and a half.

Pairing vintage photographs with modern snapshots of the same locations ‘to tell the story of the city’s rich history’, the compendium dives into the past and present of Chicago landmarks including Grant Park, Michigan Avenue Bridge and Wrigley Field baseball stadium.

The introduction to the book reads: ‘Chicago is a city that through history has triumphed over nature and disaster… [it] re-engineered the flow of the Chicago River and challenged gravity with a series of pioneering skyscrapers. It is a story of determination and pride, and the evocative photos on these pages reflect the many faces of Chicago’s heritage.’

Maguire, who works as a guide for Walk Chicago Tours, adds: ‘Chicago is a city with a history of world-class builders, writers, entrepreneurs, reformers, philanthropists, and scholars; and it is a city with a history of world-class con artists, rebels, egomaniacs, hucksters, blowhards and criminals. These were often one and the same – and all of them visionaries.

‘Born and raised here, I’ve lived on each of Chicago’s three sides, swum in its lake and sailed on its river, walked its boulevards and ridden its trains, and answer proudly whenever I am asked where I am from… its visionaries show me my city every day, newly imagined and wholly authentic.’ Scroll down to see 20 incredible archival and contemporary shots of the Windy City…

CHICAGO FROM THE AIR – PICTURED IN 1936 AND PRESENT DAY

The top picture dates back to 1936, by which time ‘Chicago was already shaping up as the home of America’s boldest architecture’, Maguire reveals. It shows some ‘recently-completed gems’, including the ‘thronelike Civic Opera Building’ (left along the river) and the ‘hulking’ 4.1million-sq-ft (380,000 sq m) Merchandise Mart on the river’s East Branch, which is still the world’s largest commercial building today. At the centre is Chicago’s ‘most famous art deco building, the Chicago Board of Trade, topped with the pyramid’. Maguire continues: ‘Just southeast of the white patch on the lakeshore at the top – Oak Street Beach – stands the Palmolive Building, another notable art deco structure. Its height and location made it ideal for the Lindbergh Beacon, installed in 1930 as a navigation aid to sailors. The building became widely known as the Playboy Building in 1967 when Hugh Hefner bought the lease and moved the magazine operations there.’ Describing the modern image, Maguire notes that the Merchandise Mart is today somewhat overshadowed by the 1968 John Hancock Center (far right) – a ‘Chicago icon’ with ‘gently tapered lines and rabbit-ear antennae’. According to the author, of all Chicago architecture, it’s perhaps the building that’s ‘most closely identified with the city’

AERIAL VIEW OF GRANT PARK – PICTURED IN 1929 AND PRESENT DAY

Grant Park – shown in the upper image in 1929 – ‘was built on 220 acres [89 hectares] of lakefront landfill in a formal French style’. Both images show Buckingham Fountain, ‘one of Chicago’s most cherished landmarks’. The pink marble fountain was ‘modelled on the Bassin de Latone at Versailles but [is] twice the size’. The book says: ’Grant Park is an early example of Daniel Burnham’s (the co-author of the 1909 Plan of Chicago architectural plan) vision of a greenbelt: miles of the lakefront as public space devoted to cultural enrichment for residents and visitors.’ Referring to the modern-day shot, Maguire says that ‘the Willis Tower and the Aon Center anchor the contemporary skyline south of the Chicago River, but along Lake Michigan, Burnham’s vision of a greenbelt prevails’. The book says that the ‘well-ordered symmetry’ of Grant Park is a ‘feature of another Burnham ideal, the City Beautiful, in which careful urban planning harmonises civic and commercial space in America’s busy cities’. According to the tome, Grant Park is also a site of citizen assembly, with the notorious protests against the Vietnam War during the 1968 Democratic National Convention and Barack Obama’s 2008 election-night rally having taken place there. During the warmer months, visitors enjoy street festivals, art fairs and firework displays at the park, the book adds

ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO – PICTURED IN 1895 AND PRESENT DAY

This ‘grand’ building (pictured top in 1895) was designed in 1893 by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge as the location for the Parliament of Religions at the World’s Columbian Exposition (a world fair) and later as the home of the Art Institute of Chicago, the book reveals. Maguire says that the building’s ‘solid horizontal lines and tall arches evoke the Richardsonian Romanesque aesthetic’ – a design style named after the 19th-century U.S architect Henry Hobson Richardson. ‘Beaux-Arts influences are evident in embellished rooflines, sculpted ornamentation and bas-relief, and classical elements like the second-floor Corinthian columns,’ Maguire writes, noting that ‘bronze lions were installed on either side of the entrance in 1894 to guard the new home of what would become a world-renowned art museum’. A vast new wing – the ‘Modern Wing’ – designed by architect Renzo Piano opened in 2009

MICHIGAN AVENUE BRIDGE – PICTURED IN 1929 AND PRESENT DAY

The book explains: ‘Until 1920, Michigan Avenue stopped at the river. The north bank bordered on scruffy landfill; the roads were unpaved and lined with soap factories, breweries and other industry. When this landmark Chicago-style bridge (pictured in the upper image in 1929) opened, it led the way for the development of humble Pine Street, the extension of Michigan Avenue north of the river.’ The bridge has two levels – two separate bridges that can be lifted independently. The author says that today, the bridge is a ‘gateway to the “Magnificent Mile”, Chicago’s upscale retail shopping district along North Michigan Avenue’. It also ‘anchors Chicago’s “second waterfront”, the Chicago River, which is surrounded by glittering architecture that has turned it into a tourist attraction’, the book reveals. Maguire explains that a 2009 renovation restored the original ornate bridge railings, which helps to ‘set the Michigan Avenue Bridge apart from the others’. To get a close-up view of the bridge’s mechanics, visitors can explore the Chicago River Museum, housed inside one of the ‘bridgehouse’ buildings flanking the structure

333 NORTH MICHIGAN AVENUE – PICTURED IN 1950 AND PRESENT DAY

According to Maguire, the front facade of 333 North Michigan Avenue (pictured top in 1950) ‘is a good match for any of the other Art Deco skyscrapers constructed in Chicago starting in the late 1920s’. The 1928 building was the last of the four ‘majestic’ skyscrapers flanking the Michigan Avenue Bridge to be completed. Maguire says: ‘The city of Chicago passed its first zoning ordinance in 1923, in response to the proliferation of skyscrapers that citizens feared would rob the city of natural light.’ According to the author, it’s unclear whether this type of ordinance bore an influence on the city’s skyscraper designs, but she notes that the setback design of Art Deco skyscrapers ‘results in only a portion of the structure reaching its maximum height, as in the 35-story tower that fronts the building at 333 North Michigan’

CHICAGO RIVER LOOKING EAST – PICTURED IN 1950 AND PRESENT DAY

The background of the top picture, taken in 1950 from the Wrigley Building, shows the locks that reverse the flow of the Chicago River, enabling fresh water to flow into the river from Lake Michigan. The book explains that the locks were put in place because Chicago had become the centre of the country’s meatpacking industry by the 1870s, with stockyards disposing of chemical waste and animal carcasses in the river, leaving it heavily contaminated. Maguire reveals: ‘Still, Chicagoans fished, swam and boated on the river, thus raising concerns about public health.’ The locks were constructed at the mouth of the river in 1889, successfully ‘flushing out much of the pollution and diverting waste products westward’. Of the modern image, Maguire says: ‘The Main Branch of the Chicago River east of Michigan Avenue has undergone massive change over recent decades, particularly in promotion of the city’s tourist industry.’ The Equitable Building (left) today occupies the spot where Chicago’s first permanent resident, John DuSable, built his home in the late 1700s. The book notes that ‘the buildings along the riverfront are mostly luxury condos, hotels, and tourist attractions’

CHICAGO RIVER LOOKING WEST – PICTURED IN 1950 AND PRESENT DAY

In the 1950 archival image above, the massive Merchandise Mart (upper right) and the 41-storey LaSalle-Wacker Building (upper left) ‘stand out as solid representatives of the Art Deco style that dominated Chicago architecture in the 1930s’. Maguire explains that the LaSalle-Wacker is made from a ‘skeleton-steel structure, in which iron columns are enclosed in brick masonry piers, a structural innovation that had become the foundation of skyscraper design’. The book continues: ‘Construction on the State Street Bridge (bottom left) began in 1942, although steel shortages during World War II and work on the State Street subway delayed completion until 1949.’ Touching on the contemporary snapshot, Maguire says: ‘Today one might describe the view looking west over the Chicago River as either enriched or obscured by the Trump Tower… either way, this structure dominates river architecture and has altered the Chicago skyline in a way that no building has in decades.’ The Trump, which is made from concrete, features ‘luxury hotel accommodations and condominiums’. The book adds that the 14,000-sq-ft (1,300 sq m) penthouse on the 89th floor was sold in 2014 for $17million (£14million)

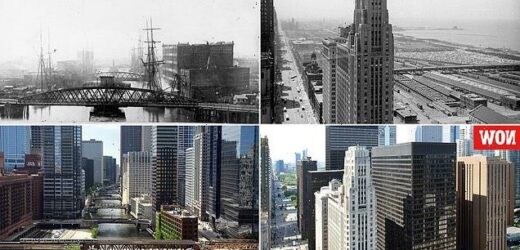

CHICAGO RIVER MAIN BRANCH – PICTURED IN 1893 AND PRESENT DAY

The black-and-white picture above was captured in 1893 and shows the swing bridge that was installed at Dearborn Street in 1888. Maguire explains that there were lots of open bridges in the city by the late 1800s because Chicago had become the biggest shipping port in the country. She writes: ‘Every day, hundreds of lumber schooners passed through harbours on the river, all controlled by the harbourmaster. The river was Chicago’s industrial lifeblood, jam-packed with freight-hauling vessels and lined with docks, warehouses, and factories.’ It’s a very different scene today. Of the modern picture, Maguire says: ‘Skyscrapers now run along both sides of the river, and its banks load passengers onto cruise ships rather than merchandise onto freighters.’ The book adds that ‘the south bank (left) is now the Chicago Riverwalk, a public walkway from the lakefront to State Street with seating areas and restaurants’

CHICAGO RIVER SOUTH BRANCH – PICTURED IN 1860 AND PRESENT DAY

‘The Lake, Randolph and Madison Street Bridges peek out of the hazy early morning light in the 1860s, the height of Chicago’s swing-bridge era,’ the book says of the top picture. It continues: ‘Traffic was bad when bridges were raised. One 1850s commentator noted: “A row of vehicles and impatience frequently accumulates that is quite terrific.”’ On the morning of July 24, 1915, more than 2,500 people boarded the SS Eastland passenger ship at the Clark Street Bridge. ‘The boat hadn’t moved more than four feet from the dock when it capsized in the Chicago River, turning completely on its side within two minutes. In the worst disaster in Chicago history, more than 800 people lost their lives,’ Maguire writes. Today, Chicago boasts 48 moveable bridges, more than any city in the world, the author reveals. Describing the modern picture, she says: ‘This photo of the downtown South Branch shows bridges (from the foreground) at Lake, Randolph, Washington, Madison, Monroe, and Adam Streets. All are Chicago-style double-leaf trunnion bascule bridges – a design that utilises balancing counterweights, or bascules, to lift each leaf on a trunnion, an axle built into the riverbank.’ The book explains that the 1916 Lake Street Bridge was the Chicago River’s first two-level bascule bridge, with railroad tracks above and street and sidewalk below

WRIGLEY FIELD – PICTURED IN 1915 AND PRESENT DAY

‘One of the oldest ballparks in the country, Wrigley Field was built in 1914, Maguire writes, adding that ‘a live bear cub was on hand when the team played its first game’. The photograph on the top winds the clock back to 1915, when the stadium was called Weegham Park after the Cubs’ first owner, the book reveals. It was renamed in 1926 after the team’s new owner, William Wrigley. The book reveals: ‘Dedicated to tradition, for years Wrigley was one of the few stadiums with a manually operated scoreboard, and it was the last major-league ballpark to install modern lighting.’ In 2012 the Cubs’ owners, the Ricketts family, proposed major renovations, which began in 2014, setting out to preserve the ‘historic charm’ of the stadium. Upgraded seating, a larger variety of concessions, roomier concourses, and two jumbo LED screens were introduced as part of the overhaul. Maguire writes: ‘In 2016 the Cubs defied all odds, winning the National League Championship Series and the World Series. The Cubs had not played in a World Series since 1945 and had not won a World Series since 1908. Despite their 108-year championship drought, fans remained loyal and passionate, and continued to fill the seats day and night’

Chicago Then and Now by Kathleen Maguire is published by Pavilion and retails at £14.99

Source: Read Full Article