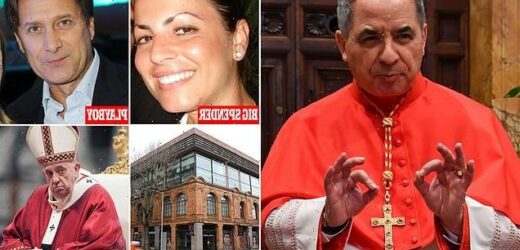

Sex, lies and cardinal sin? A plot like a Dan Brown novel and characters including the Pope’s saint-maker, his ‘Mata Hari’ fixer, and a secret cabal accused of siphoning millions from Vatican coffers. The result? A most unholy scandal, writes GUY ADAMS

As a tidal wave of cash flowed into London’s super-prime property market, the deal that saw a former Harrods car showroom in Chelsea change hands for £129 million generated barely a ripple of interest.

Like many a property in this gilded corner of our capital, the Edwardian brick building on Sloane Avenue was to be converted into 49 luxury flats, with a smattering of top-end shops beneath to cater for residents.

The buyer, an opaque company named 60 SA Limited and registered in the tax haven of Jersey, hoped to sell them for a total of £400 million and turn a handsome profit.

Pope Francis attends a Mass on the solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul at St. Peter’s Basilica on June 29, 2021 in Vatican City,

Proceedings culminated on Tuesday at a special court in the Holy See, where a former ally of Pope Francis, Angelo Becciu, (pictured) became the first Cardinal since the 17th century to stand in the dock at a criminal trial

That was back in 2012. Today, the flats have long since been built and the building’s ground floor is occupied by fashion boutiques, art galleries, delicatessens, and an ultra-posh health club where membership starts at £615 a month.

However, the original deal that led to this monument to Mammon imploded, spectacularly, leaving a major investor — The Vatican — with serious financial losses. It appears to be tens, if not hundreds, of millions of pounds out of pocket.

The Chelsea property, as a result, is at the centre of an epic corruption scandal implicating some of the most senior figures in the Catholic Church.

Allegedly, it involves sex, money, prostitution and money-laundering by senior Vatican power-brokers — along with an unlikely blackmail plot so sensational that you’d be forgiven for thinking it had been plucked from the pages of a Dan Brown novel.

For the case is perhaps the worst corruption crisis for the Catholic Church since the early 1980s, when Roberto Calvi — a financier famously known as ‘God’s Banker’ because of his links to the Vatican — was found hanging beneath Blackfriars Bridge in London, his pockets stuffed with bricks and more than £10,000 cash in three currencies.

Proceedings culminated on Tuesday at a special court in the Holy See, where a former ally of Pope Francis, Angelo Becciu, became the first Cardinal since the 17th century to stand in the dock at a criminal trial.

Previously a senior Vatican diplomat, and once regarded as the Pontiff’s de facto chief-of-staff, 73-year-old Becciu was until last year also in charge of Francis’s ‘Saint-making office’ which decides whether to canonise mere mortals. Some tipped him as a leading contender to become the next Pope. Now he faces eight criminal charges.

Also on trial in the case, which has transfixed Italy, are nine highly-colourful co-defendants.

They include Raffaele Mincione, a playboy Italian financier; Cecilia Marogna, a glamorous Italian intelligence expert nicknamed the Vatican’s Mata Hari; and Fabrizio Tirabassi, a long-serving Vatican accountant found to have a Swiss bank account containing 1.3 million euros plus a collection of coins and medals worth 8.5million euros.

Together, they face a total of 78 separate charges laid out in a 487-page criminal indictment which dubs them ‘actors in a rotten, predatory and lucrative system’ who for years used the Church’s bank accounts as ‘a sort of ATM’ to illegally enrich themselves and their families.

And 30,000 pages of supplementary evidence portray the Vatican as a nest of corruption and vice.

Prosecutors claim they document hefty illegal bank transfers, text messages between collaborators, bags of cash changing hands, secret meetings in luxury hotels and tranches of Church funds being splurged on prostitutes and luxury goods from Prada and Louis Vuitton stores.

For their part, the defendants deny wrongdoing. They say they are blameless victims of a witch-hunt which began shortly after Pope Francis, 84 — who took office in 2013 — declared a ‘war on corruption’ at the Vatican, where the management of vast financial reserves has been dogged by scandal for decades.

Police in the City State, which has its own justice system and even jail, duly began to scrutinise ‘Peter’s Pence’ — donations which pious Catholics hand to the Church — were being spent.

Giuseppe Pignatone, one of Italy’s most feared anti-mafia judges who helped bring down the ‘capo’ of the Sicilian Cosa Nostra, was brought in to head investigations.

It soon emerged that millions, and perhaps billions, of euros were being spent with little oversight. In some cases, huge fees seemed to be earned by the network of advisers and officials who were helping the Vatican funnel cash into exotic, often risky investments.

Often, they seemed to be making vast profits while the Church suffered mysterious losses. There were also suspicions that Vatican officials who signed off the deals were being handed kickbacks.

And very soon the former Harrods car showroom in Chelsea, into which the Holy See seems to have ploughed about £200million, became the focus of their inquiry.

Details of the Church’s investment in the venture emerged in 2019 when Vatican police raided the offices of the Secretariat-of-State, the Holy See’s all-powerful civil service. This had been run by Becciu between 2011 and 2018 and (among other things) presided over a real estate portfolio that included 5,251 properties across Eur-ope, including 1,200 in London, Paris and Switzerland.

According to the criminal indictment, they seized papers showing that the Secretariat had in 2014 decided to plough £170million into an investment fund run by the previously mentioned Raffaele Mincione.

Half of that sum was placed in what prosecutors describe as ‘imprudent and speculative’ financial products. The other half was used to take a 45 per cent stake in the Sloane Avenue property. Prosecutors claim the deal ‘grossly overestimated’ the building’s real value.

By late 2018, the investments had already lost about £15 million, court papers claim, prompting the Vatican to seek an exit strategy that would ‘salvage what was salvageable’ and cut ties with Mincione and his fund.

A general view of 60 Sloane Square, a period building in West London owned by the Vatican on February

A broker, Gianluigi Torzi, was hired to negotiate the purchase of the rest of the building. He did so in return for an additional £40 million.

Prosecutors claim, however, that Torzi hoodwinked the Vatican into structuring the deal in a way that meant he was left owning all the voting shares in the firm that controlled the Chelsea property.

They say he then extorted another £15 million from the Church to properly acquire the building — which the Vatican thought it had already paid for. He denies wrongdoing.

Two senior figures in the AIF, the Vatican’s financial watchdog, who allegedly overlooked the anomalies of this transaction, are also on trial. So too is Nicola Squillace, a Milan-based lawyer who structured the London deal for the Holy See, and Mauro Carlino, a staffer in the Secretariat. They will also plead not guilty.

Fabrizio Tirabassi, a Vatican official who acted as its point of contact with Torzi and is accused of profiting fraudulently from the deal, is also in the dock. When police raided his two homes, they allegedly found shoeboxes full of cash, Swiss bank records and valuable coins and medals.

He is also accused of offering Torzi a prostitute as an inducement to complete the Chelsea property deal, a claim he denies.

Of all those on trial, the biggest by far is Becciu, previously linked in the British press to the Vatican’s surprise (and decidedly canny) investment — reportedly one million euros — in the 2019 Elton John hit biopic, Rocketman. (The singer himself — while criticising the Vatican’s refusal to bless gay marriages — had highlighted the apparent hypocrisy of investment in a project which was heralded as the first major film to show a gay male sex scene and indirectly celebrate gay marriage.)

Such was Becciu’s status in the Catholic Church that Pope Francis had to change Vatican law so he could be charged in a criminal court (previously, Cardinals could only be tried by their peers). He was also sacked from the canonisation office by the Pope last year.

The indictment accuses Becciu of draining Vatican reserves through the original investment, which he signed off while running the Secretariat in 2014, and of overseeing the disastrous efforts to salvage it. He’s further accused of tampering with witnesses by trying to persuade an underling to cover up for him when investigators began probing the deal.

While there is no suggestion he sought to line his own pockets with any fraud, the Cardinal is also charged with funnelling hundreds of thousands in Vatican funds to friends and family members.

Prosecutors claim, for example, he arranged for 800,000 euros to be sent to a charity run by his brother. The cash, they say, ended up being ‘widely used for purposes other than the charitable purposes for which they were intended’, including a loan to his niece to help her acquire a property in Rome.

Friends of Becciu say that, serious mistakes were doubtless made over the Chelsea deal, but it was overseen mainly by junior officials.

‘His Eminence oversaw a large ministry with responsibility for everything from diplomatic missions to writing the Pope’s speeches,’ says one. ‘Financial matters were delegated to an administrative office which he had limited involvement with.’

They add that all funds sent to his brother’s charity were properly accounted for, and invoices and bank statements prove it was correctly spent — much on building a bakery in a deprived area of Sardinia that employs 15 people and helps feed the local poor.

Then there are the curious payments Becciu seems to have funnelled to the tenth defendant, Cecilia Marogna, a glamorous 40-year-old Sardinian with an appetite for luxury, who he hired as an external security consultant.

She has been dubbed ‘Mata Hari’ and ‘the Cardinal’s lady’ by the Italian Press, who allege her role sometimes involved acting as a sort of spy providing Becciu with intelligence that might be used to blackmail potential enemies seeking to expose corruption within the Vatican.

Prosecutors allege she embezzled 575,000 euros in Church funds that Becciu claimed to be sending her to use as a ransom to free Catholic hostages abroad.

Bank records from a Slovenian ‘front’ through which her earnings were channeled show that some of the cash was used instead to pay bills at luxury shops and hotels.

Marogna denies embezzlement, and has told Italy’s Corriere della Sera newspaper that, over four years, Becciu wired her the cash as payment and expenses for her work using ‘a network of relationships in Africa and the Middle East to protect nunciatures [offices of papal ambassadors] and missions from environmental and terrorist risks’.

She claimed some of the money spent on luxury goods — £2,000 at Prada and £7,300 at Chanel — was essential for carrying out her duties on behalf of the Vatican.

Although she was close enough to the Cardinal to have an overnight stay at his flat in September 2020, according to prosecutors, she dismisses as ‘absurd’ talk of her being Becciu’s lover.

There are curious payments Becciu seems to have funnelled to the tenth defendant, Cecilia Marogna, (pictured) a glamorous 40-year-old Sardinian

Also on trial in the case, which has transfixed Italy, is Raffaele Mincione, (pictured) a playboy Italian financier;

Sources close to Becciu, for their part, say the cash was used as a ransom to help free a nun, and they deny that Maronga acted as a spy for him.

A final layer of intrigue in this complex but fascinating tale involves a rival of Becciu named Cardinal George Pell. One of the most high-profile critics of financial corruption in the Vatican, Pell suffered an extraordinary fall from grace in 2017 after being charged with sex abuse against minors in Australia decades previously.

He was tried and found guilty, only to be freed by the country’s High Court last April, having served a year behind bars.

In an extraordinary miscarriage of justice, it emerged that Pell’s conviction had been based on the uncorroborated testimony of a single witness. There was almost no supporting evidence, and multiple contradictory accounts which cast severe doubt on his acccuser’s credibility.

Following Pell’s release, allegations then began to appear in the Italian media that Cardinal Becciu had sent money to Australian bank accounts as payment for testimony against Cardinal Pell. It was alleged that this was motivated by a desire to interfere with his anti-corruption campaign.

There is little documentary evidence to support such rumours, however, and they are vigorously denied by Becciu, whose friends describe it as a ‘conspiracy theory’.

Whatever the outcome, the case is yet another devastating blow for the Catholic Church, still reeling from the child sex abuse perpetrated by paedophile priests and monks stretching over many decades.

And, of course, the fate of God’s banker, Roberto Calvi, murdered at Blackfriars — less than five miles from that exclusive Chelsea property now at the heart of this seismic corruption case — can never be too far from the thoughts of those involved.

Not least because a Calvi associate, Sicilian financier Michael Sindona, who advised the Holy See on investments, was murdered a couple of years later, when his coffee was laced with cyanide.

Little wonder that the defendants, as well as several witnesses, are said to be watching their backs.

‘His Eminence feels great sorrow and pain that he has been sent to trial by order of the Holy Father,’ says a friend of Becciu.

‘However, he also respects the process and looks forward to having his innocence recognised by the court, and to demonstrating to both the Pope and the World that he’s innocent.’

The trial, which adjourned this week, will resume in October and is expected to last until the New Year. There is no jury. Instead, a panel of three judges will decide whether each of the ten defendants — including the man once tipped as a future Pope — are guilty or not guilty of what you might call a cardinal sin.

Source: Read Full Article