The masterchef with an insatiable appetite for women: He was the French butcher’s son who baked Churchill’s birthday cake – and changed Britain’s culinary tastes for ever. As Albert Roux dies at 85, RICHARD KAY looks back at his saucy story

But for the clammy embrace of an elderly priest, the culinary fortunes of this country might never have been the same.

As a boy of 14, Albert Roux was training for the priesthood in his native France when an unholy encounter with a ‘smelly’ man of the cloth saw him switch from clerical robes to chef’s whites.

It was the most providential change of direction for his adopted country, Britain, whose eating habits he would change for ever. It was also a wise decision. ‘I would have made a very bad priest because I am — was — a philanderer,’ said the restaurateur, who has died aged 85.

‘Imagine myself visiting a nunnery, that would have been bad . . .’

Indeed, Roux’s weakness for women was as pronounced as the rich soufflé suissesse that was among his signature dishes.

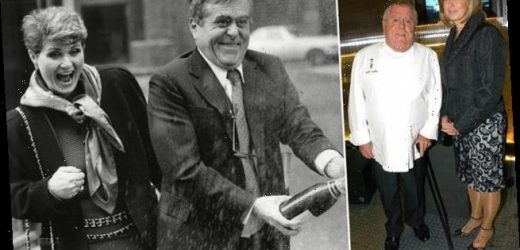

As a boy of 14, Albert Roux (pictured with his wife Cheryl) was training for the priesthood in his native France when an unholy encounter with a ‘smelly’ man of the cloth saw him switch from clerical robes to chef’s whites

Not that this addiction to the fairer sex was as fine-tuned when he first arrived here in 1953. ‘I didn’t have a great perception of this country,’ he recalled. ‘I thought the women were ugly and flat-chested, but that turned out not to be a true reflection of the English rose, as I discovered to my great pleasure.’

On his new country’s post-war food, he was on firmer ground. ‘There was still rationing, which had ended in France in 1946. Britain was a total gastronomic desert.

‘Just Joe Lyons (the tea room chain) and a biscuit or Swiss roll wrapped up in beautiful paper,’ he said recently, before remarking on how things had changed. ‘Nowadays the taxi driver discusses lobster.’

For that we are indebted to the thrice-married boulevardier whose death comes just ten months after that of his younger brother, Michel, with whom he changed the way the world felt about British food.

They made gastronomic history in 1982 when their London restaurant, Le Gavroche, with its eye-wateringly pricey French menu, became the first in Britain to be awarded three Michelin stars.

Their impact was not just on the food we eat and the way we cook it, but in influencing a generation of chefs who have come in their wake. Indeed the roll call of chefs who went through the doors of Le Gavroche and The Waterside Inn, the Roux brothers’ Thames-side restaurant in Berkshire, was a significant proportion of the contemporary British restaurant scene.

Indeed, Roux’s (pictured with his wife Monique) weakness for women was as pronounced as the rich soufflé suissesse that was among his signature dishes

Gordon Ramsay, who earned his stripes at Le Gavroche, led the tributes. ‘So, so sad the (sic) hear about the passing of this legend, the man who installed Gastronomy in Britain,’ he wrote on Instagram.

Marco Pierre White, Marcus Wareing, Rowley Leigh and Monica Galetti also rose through the ranks at Le Gavroche. In his tribute, TV chef James Martin described Roux as ‘a true titan of the food scene [who] inspired and trained some of the best and biggest names in the business’.

But while Michel Roux was famously dismissive of the era of the celebrity chef, brother Albert was more nuanced. Asked about Gordon Ramsay’s notorious temper, Roux suggested that a good kitchen needed to have humour and humanity. ‘In my days my washer-up was king and he was treated decently,’ he said.

He did make an exception for the famously fiery Marco Pierre White, whom he had employed aged 19. ‘He is truly a talented man . . . but he has got a chip on his shoulder. No, there is something wrong with Marco.’

Nor was he at all high-minded about food, admitting to a secret love for Big Macs.

The eldest son of a butcher from eastern France, Albert Roux left school at 13. He never revealed what happened to make him change vocation beyond saying: ‘Something happened, something you read about in the papers.’ A year later was he apprenticed to a patissier in Paris.

Through his godfather, chef to the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at their mansion in the Bois de Boulogne, he secured a job as scullery boy for Lady Astor, the first woman to sit in Parliament.

He arrived at Cliveden, the Astor mansion, during the shooting season and his first task was to pluck pheasants, woodcock and pigeons without spoiling their skin.

He recalled his first week’s employment with a shudder. Lady Astor had six people for lunch and they ate asparagus with Hollandaise sauce. ‘At 2.30 she came downstairs and berated the chef. He had made the Hollandaise with margarine. ‘Do we not have cows on the estate?’ she asked acidly.

Apart from one terrible bungle, when the Oeufs en Cocotte destined for serving prime minister Harold Macmillan were jammed in the dumb waiter by the young commis de cuisine, the apprenticeship went smoothly. Roux returned to France for national service and, after being demobbed, was shocked to find that the British would not renew his work permit.

He ended up back in Paris, working in the kitchen of the British Embassy. One day the ambassador’s wife requested rice pudding for a special guest, the war hero Viscount Montgomery.

Monty adored it, and after supper the young Roux was summoned by the ex-soldier. ‘He gave me an envelope containing a ten shilling note and a note saying it was the best rice pudding he had ever tasted.’

Soon, thanks to ambassador Gladwyn Jebb, Albert was back in Britain with his childhood sweetheart, Monique, whom he married in 1959 and with whom he had two children. He was now working for the family of the Queen Mother’s racehorse trainer, Major Peter Cazalet. And soon he was impressing another celebrated palate, that of Winston Churchill.

His dish this time was an extravagant birthday cake, decorated with violets and a marzipan cigar.

‘He asked to see me,’ Roux recalled later, ‘and pointed to a painting on the wall. ‘That is art and this is art,’ he said. ‘The only difference is that this will be forgotten tomorrow.’ ‘

Roux stayed at Fairlawne, the Cazalet house in Kent, for eight happy years. And then in 1967, with £3,000 savings and money borrowed from friends including the Cazalets, he and Michel, five years his junior, who had followed him to Britain, opened Le Gavroche in Chelsea. First-night guests, including Charlie Chaplin, Sophia Lauren, Ava Gardner and Robert Redford, flocked to celebrate the arrival of a new ‘star’.

With uncompromising standards, elaborate presentation and first-rate service, it raised the standards of haute cuisine in a then limited English restaurant scene. It moved to Mayfair in 1981, and soon became the first British-based establishment to carry the maximum three Michelin stars.

‘An Olympic gold medal,’ Albert said at the time. ‘I have had no other ambition.’

At the height of its popularity in the 1980s, securing a table required a lot of planning — or bare-faced cheek. ‘The waiting list was often three months long, and the only way round it was a generous inducement to the doorman,’ recalls a regular diner.

Its kitchen would become the training ground for a new generation of British chefs. The brothers launched the Roux Scholarship, an annual competition, in 1983, with many scholars going on to win Michelin stars of their own.

Albert and Michel opened a string of other restaurants, fronted a 13-part TV series on BBC2 in 1990, and published a series of best-selling books about French cookery.

Domestic life, however, always came second. Marriage to Monique ended in divorce in 2001, and despite a well-nourished girth Albert became a ladies’ man about town. Soon he was dating Cheryl Smith, an elegant Zimbabwean who was 27 years his junior.

Initially, Cheryl rejected his advances, aware of his reputation for carrying on multiple affairs.

‘When I met Albert, he had seven girlfriends, two of whom believed they were living with him,’ she once said.

‘I told him I wasn’t prepared to be part of his harem.’

Undeterred, Roux spent seven months wooing her, and discarding his other girlfriends, before finally Cheryl agreed to date him.

They married in 2006 and at first the relationship seemed to go well, with Cheryl said to have played an important part in the business.

But the marriage ended after he was reported to have begun an affair with a hat-check girl at one of his restaurants.

He married for a third time in 2018, to Maria Rodrigues, a director at accountancy firm KPMG.

Not long ago he reflected on his marital ups and downs. ‘If I had to redo my life I would try to keep away more from women,’ he said. ‘I was born a womaniser and I adore the company of women, and not particularly for sex.’

As for affairs, he quipped: ‘OK it’s bad, but it doesn’t affect your cooking.’

For which British diners can only be grateful.

Source: Read Full Article