Mark Bouris sits down and orders a main course of working my arse off with a side order of cut the bullshit.

We have never met, but I kind of feel that I know the multimillionaire founder of financial planning firm Yellow Brick Road and Wizard Home Loans (which he sold to GE for more than $400 million) through his media ubiquity: TV shows, podcasts, newspaper columns.

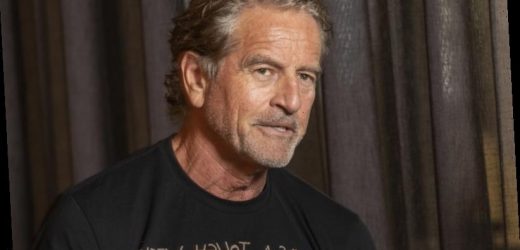

Mark Bouris arrives at lunch with a bit of a shiner from his boxing training.Credit:Louie Douvis

And now there’s his new book Rise, a sometimes aggro, how-to/self-help stream of consciousness manual about the business of being Mark Bouris. “You might be thinking, I can’t do that, I can’t be Mark Bouris. But the fact is you can.”

It’s a deliberate sweary (it forces people to take notice) guide to getting ahead the Mark Bouris way, which involves a lot of old-fashioned hard work and zero tolerance for bullshit. The book is repetitive and undisciplined (he admits he didn’t actually put pen to paper but dictated it), occasionally inspiring, and it’s also fizzing with complex ideas translated into Bouris.

Those namechecked include: Maya Angelou, Peter Sellers, Kerry Packer, Vedic Mathematics, Robert Menzies, Sun Tzu, Leonardo da Vinci and Machiavelli. The genius of Stephen Hawking is used to demonstrate the benefits of divergent thinking. “His brain just sat there thinking about this shit all day long.”

Bouris has a method to eating his District chicken salad.Credit:Louie Douvis

In reality, Bouris is less aggressive and more unassuming as he arrives five minutes early for our midday booking at District Brasserie, the Mediterranean restaurant at the base of Sydney’s Chifley Tower, where bankers, lawyers, executives and civil servants efficiently power-lunch amid dark green marble and aged brass fittings.

The silver fox, 65, has turned up in attire more frequently seen on a man one third his age — black jeans, black trainers and a black t-shirt emblazoned with the slogan he proudly displays: “It was a tough week, but f#ck I survived it.” Bouris also sports a pair of notable biceps and a shiner courtesy of a morning sparring session with some coppers at the Woolloomooloo Police Citizens Youth Club.

On a boxer’s diet, the boy from Punchbowl in Sydney’s south-west is off alcohol but insists I upgrade my gin and tonic to a Four Pillars. It is a demonstration of friendly Greek hospitality (the restaurant is owned by a cousin), but also an exercise in charm, and yes, his powers of persuasion.

The waiter already knows Bouris’ regular order, which is considerably more healthy than my grilled crumbed tiger flathead with layered pommes anna and crushed green peas.

The District chicken salad is a mainstay of the brasserie and Bouris has his own idiosyncratic method for consuming it.First, he eats all the green leaves. Then he eats the chicken. Then only one half of the outsized square of feta cheese. But the little silver dish of cherry tomatoes remains untouched. Too much oil. There is no dessert.

As a father, he would frequently miss events and was “always backfilling”.

Later he reveals his boxing fitness regimen is not the only reason he avoids alcohol.

“I used to drink a lot but alcohol is not a good thing. I can get a bit reckless. Crazy, daredevil. I can do stupid stuff and that can lead into something worse.”

Grilled crumbed tiger flathead with layered pommes anna and crushed green peas.Credit:Louie Douvis

The book talks of David Gyngell, whom we both know, and who played a crucial part in Bouris’ early rise.

They now both have property on the same street overlooking Byron Bay, as does TV producer John “Strop” Cornell.

Gyngell famously quit his job running Channel Nine for a quieter life, astonishing the industry by moving to Byron Bay with his family. But Bouris corrects me — Gyngell is not leading a quieter life, but a different life.

“David is very smart — he knows when to get out. Not many people do.”

It seems that Bouris does not, and after revolutionising how we shopped for home loans and financial advice, the book reveals Bouris’ ambition is to tackle another broken system: politics.

But before that is his life story.

After marrying Bouris’ Irish-Australian mother, the businessman’s Greek father had to constantly slog his guts out after his family cut him out of the will. Bouris learnt his Stakhanovite work ethic from his dad, but it was his mum who altered the course of his life by forcing him to go to university.

Bouris talks about only fragments of his personal life in his book. He brought up four boys after his first wife became ill and they moved in with him. Typically, he strived for maximum efficiency in his child rearing, recruiting his office cleaner to become his driver, buying him a car so he could pick up the boys from school and deliver them home to a housekeeper who would cook dinner.

“I always ate with my boys, then I would go upstairs to my area and do more work and they would go and do their homework or whatever.”

The businessman is refreshingly direct during the meal, but when he is talking about how he didn’t see enough of his four boys growing up, the trademark direct eye contact fades a bit and he ends up looking over my shoulder.

As a father, he would frequently miss events and was “always backfilling”. “I never went to one parents’ meeting. I never saw them do their homework.” His four boys, Alexander, James, Nicholas and Dane, have worked for him or with him at different times; it was “the dream”, he says.

Mark Bouris in corporate guise at his Sydney office in 2013.Credit:Louise Kennerley

Bouris is private about his personal life , but says he does have “a girl I take out”.

The key concern of the book is about what’s broken and how to fix it. He sees broken systems everywhere: politics, media and particularly social media, which bends people’s behaviour out of shape.

“Social platforms have extraordinarily well researched the psychology of how we live our lives. And they’ve got it to become compulsory. They’ve actually tapped into narcissism in a big way. Like me, follow me. They are promoting narcissism on a grand scale, but on an individual level. I think the opposite of narcissism is gratitude.”

Does he have to address narcissism within himself?

“All the time. We all have that basic instinct to be liked. To get a tick of approval.”

Hence the boxing. “I fight to keep my feet on the ground. In a boxing ring, you are on your own. Boxing keeps me from being my own worst enemy.”

And while he is an entertaining companion over lunch, I imagine his exacting standards in the office would be exhausting for any of his employees. Is he a demanding boss? “No, just intense. I am always at them.”

Bouris is matter of fact about the transactional nature of our meeting. Lunch is extremely pleasant and stimulating, but there is a book to promote: “I know why I am talking to you and why you are talking to me.”

Sounds like time to provoke him, so I ask how much money he has. I fail.

“What is my net worth?” A thoughtful pause. “Hundreds. Hundreds of millions.”

Does he want to be precise? “Nup. The figure we arrive at today might not be applicable tomorrow.”

The thing about being rich is that there is always someone else richer, and Bouris is self aware enough to know this. So what does success look like? Here he gives an answer so unexpected I have to get him to repeat it.

“Change. Making changes, affecting changes, permanent changes. Changing the way we do things.”

He admires the entrepreneurs Elon Musk and Richard Branson for changing how we consume, but a key part of his agenda is to change people within themselves.

While the system is rotten, what he really wants to change is the voters.

Here he enthuses about his Wimp 2 Warrior business, a global physical training system where any old Joe can undertake a structured training course in mixed martial arts and step into the octagon arena and fight. I decry the violence, but here he turns evangelist. It is not about the violence, he says, but for people to step out of their comfort zone and change. And grow.

Eventually, our conversation leads to the same destination as his book: to politics.

Just like parts of society, and social media and people blocked from achieving their dreams, politics is broken.

“Politics needs to change. Democracy doesn’t exist any more for me.”

But while the system is rotten, what he really wants to change is the voters. “I would like us to become more critical, to be less convergent, think more broadly. I’m not saying don’t comply with the rules. But make a decision as to why you are complying with the rules.”

Bouris with Kerri-Anne Kennerley hosting Celebrity Apprentice in 2015.

Time and time again, research shows voters want policies that occupy the middle ground.

“But democracy doesn’t sit in the mean, it is being pushed to the two ends. It is being pushed by the system and the system needs to f—–g change.”

He then launches into a tough critique of both major parties.

“Once upon a time, Labor stood for really good, solid social values. Today, it stands for the 1000 interests that it represents. And the Liberals, the conservatives, don’t stand for middle Australia. You know, the toffs, they ran it, but they knew they had to go to the middle class.

“It doesn’t have the middle class anymore. It stands for big business and your greedy people, who think it’s all about the Mercedes-Benz or expensive lunches and making shitloads of money. And it kills me.”

He talks about iconic Liberal prime minister Robert Menzies and how Menzies harnessed the electoral power of the “forgotten people”. “Well, I think there is a new forgotten people. And that is what I want to see change.”

Bouris wants to create a vast system, a citizens’ army of data and opinion, a lobby group to use its collective power to make data-driven decisions.

“The question in a electoral sense is, do people give a f—k or is it just me being mad?”

To be honest, it sounds as far fetched as Wizard Home Loans once did.

It will come down, as it always does, to leadership, and whether Bouris, who wants to be involved in politics but detests the system and how it ruins people, wants to do what he has always denied he wants to do and lead it.

At one point, I bluntly ask, “are you mad?” Bouris stops, a lettuce leaf hovering midway between his plate and mouth and then assents. “I think everyone’s a little bit mad.”

Rise by Mark Bouris is published by Hachette.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article