Victorian MPs – from all sides – seem to have collectively decided that nothing they do in the first few months of this term of parliament is going to define the next electoral contest.

But the electoral success of the Andrews government hasn’t rid it of the corruption scandals, policy headaches and deteriorating debt position – projected to be $116 billion by June 2023 – that it now must address.

That includes the three unresolved corruption reports kept from the public ahead of the election.

Premier Daniel Andrews will need to use the first year of the new term to remove the political barnacles threatening to weigh down his governmentCredit:Luis Ascui

The public may have become accustomed to governments dropping damaging reports on days when we are collectively distracted, like Melbourne Cup Day, but we shouldn’t let them bank on us – the voters – letting them off the hook just because we don’t vote for another four years.

Developer John Woodman leaving the IBAC hearing in 2019.Credit:Justin McManus

During the election campaign the state’s corruption watchdog was granted an injunction that prevented the publication of a draft report into Operation Daintree – a secret investigation that involved Premier Andrews being interviewed over an alleged $3.4 million promised payment to a union.

This meant Victorians were left to cast their vote without knowing exactly how the state was being run.

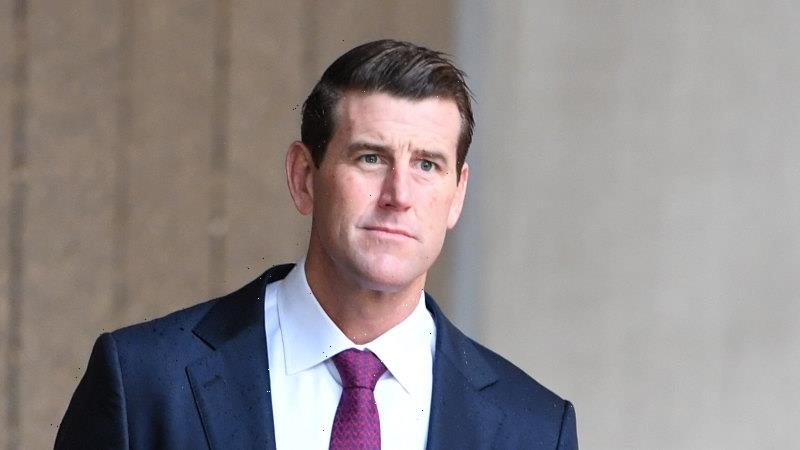

Public hearings for Operation Sandon, an investigation over allegedly crooked land deals in Melbourne’s south-east, started in 2019, but Victorians remain in the dark about the investigation in which Andrews was allegedly interviewed over his association with the property developer John Woodman.

It’s now expected that this report will be tabled in the first half of 2023 which would come at the right time in the election cycle for the government, but should not mitigate political scrutiny.

Then there is Operation Richmond, an investigation into negotiations between the state government and United Firefighters Union, which has been running since 2019. It poses a political risk for the government and the findings have been kept from the public.

It's likely that 2023 will be deemed the most politically favourable time to deal with these scandals, but any adverse findings should not be dismissed simply because of the government's recent electoral success.

On the policy front, Andrews has already set about dealing with one of the biggest drags on his government – the state’s ailing health system. The election result may have been resounding, but that doesn’t mean the government can continue as is, without finding a fix.

Victorian Premier Daniel Andrews and NSW Premier Dominic Perrottet have teamed up to demand help from the federal government to fix the healthcare systemCredit:Jules Boag

Last year it was politically advantageous for Andrews to pick a fight with the federal government when Scott Morrison was in The Lodge. His decision to cosy up to NSW Liberal premier Dominic Perrottet also caused headache for the Victorian Coalition in November, undermining their argument that the health woes were of Labor’s making.

Andrews is likely to spend the next few months exploiting this dynamic and continuing to pick fights with Canberra as he demands action on the health system and moves to reverse the declining bulk-billing rates.

Arguably the greatest policy challenge for the Andrews government will be the state’s finances. Ahead of the election, a Standard & Poor’s analysis found Victoria’s fiscal position was the weakest the agency had ever seen, with the state hurtling towards a debt of $195 billion by mid-2026.

Yet, during the election the government failed to announce any new taxes or cuts, banking on growth to get it out of its financial black hole. The budget in May is likely to explain what the government hasn’t – whether that forecast growth will be enough to repair the budget over the long term, or whether they’ll need us to chip in.

Then there are those pesky policy issues the government spent the past 18 months dodging and delaying until after the election campaign.

At the top of the list is the state’s second medically supervised injecting room. A review of the first facility in North Richmond found it had saved lives, but it has caused the government political headaches with many residents and business owners. The newest facility will be built in Melbourne’s CBD, but the government failed to finalise the location before the election. Conveniently, a report recommending a site was delayed until, you guessed it, 2023.

In political circles these issues that weigh down governments are often referred to as “barnacles” – those small sea creatures that slowly build up on the bottom of the boat, impairing its efficiency.

Conservative political strategist Sir Lynton Crosby famously used this analogy when he advised UK prime minister David Cameron to remove the "barnacles off the boat" when pushing the need to remove distractions before the UK general election.

At the time, Cameron was late in the election cycle but heeded the advice. Ideally, governments would act much sooner.

Daniel Andrews knows this all too well. Back in 2015, the newly elected premier pried off perhaps his biggest barnacles within a year of winning when he paid more than $1 billion in taxpayers’ cash to scrap the East West Link road project, despite pledging that the contract could be ripped up at no cost.

Doing so early in the election cycle meant he carried almost no political cost. Even the most effective opposition leader would struggle to campaign on such a juicy issue for a full four years.

If history is to be any guide, 2023 will be a year of backflips, blowouts and finding the answers we were owed long before polling day.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article