Elvis ★★★

M, 159 minutes

Few showmen of our day have given us more of the old razzle-dazzle than Baz Luhrmann, whose movies often appear to have no subject beyond their maker’s dedication to throwing stardust in everyone’s eyes – including his own.

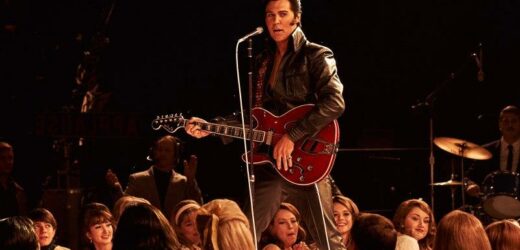

Austin Butler in a scene from Elvis. Credit:Warner Bros. Pictures via AP

Personally, I yearn to see him tackle an updated version of The Music Man, starring his old pal Hugh Jackman and rescored by Kanye West – but until that day dawns, we can make do with Elvis.

Shot on the Gold Coast and reportedly budgeted at a relatively modest $US85 million ($122 million), this zany biopic has its longueurs and is no more historically reliable than you’d expect. Still, as an antipodean fever dream it’s significantly more compelling than previous Luhrmann follies like The Great Gatsby or Australia.

Re-mythologising Elvis (played by Austin Butler), the most mythic figure in rock ’n’ roll history, is what you might call Bazness as usual. The surprise is that Luhrmann’s take on the legend may well be his nearest approach to a heartfelt love story, with apologies to Romeo + Juliet stans.

Austin Butler as Elvis, Helen Thomson as Gladys, Tom Hanks as Colonel Tom Parker and Richard Roxburgh as Vernon.Credit:Hugh Stewart

To be clear, we’re not talking about Priscilla (Olivia DeJonge), who gets one lively scene and then is mostly shown gazing at her man with silent adoration, until it’s time for her to storm out of Graceland in high ’80s telemovie style (she doesn’t say “You’ve changed, Elvis,” but she might as well have).

No, the thesis of the film is that the central, defining relationship in the King’s life was his co-dependent bond with his manager Colonel Tom Parker, played by a latex-encased Tom Hanks as a waddling old sinner with a comedy Dutch accent and an eye for the main chance: Elvis’ benefactor, enabler and jailer, the beast to his beauty, Santa Claus and Svengali in one.

Typically for latter-day Luhrmann, Elvis is less a cohesive narrative than a collection of shards glued together by music and voice-over, with the Colonel in this case serving as narrator – a transparently unreliable one, which supplies a handy get-out clause as far as accuracy is concerned.

In this telling, their fateful encounter occurs in 1955 at the Louisiana Hayride, where a youthful Elvis initially appears to be shaking from nerves more than anything else. Once on stage, though, he leaves his inhibitions behind, inspiring ecstasy both in the largely female crowd and in Parker watching from the wings.

The other love story: Austin Butler as Elvis and Olivia de Jonge as Priscilla.Credit:Courtesy of Warner Bros

“He was my destiny,” Parker tells us. A sometime carnival barker and eternal hustler, the Colonel may not know much about music but he understands showbusiness – especially the “biz” side of the equation, or what a character in Sweet Smell of Success called “the theology of making a fast buck”.

The implication is planted that rock ’n’ roll is just one more sideshow act, if not an outright con game. Yet these suspicions cast almost no shadow on the film’s Elvis, whose public swagger gives way offstage to a childlike helplessness: repeatedly we see him striving to spread his wings as an artist, only to find destiny, in the form of the Colonel, holding him back.

As for the lead performance, it’s fair to say that almost anyone would look low-key compared to whatever Hanks is doing. Butler, who does some of his own singing, is no slouch as a mimic but stronger on aw-shucks charm than insolence: this is an Elvis who smiles more than he sneers, and nearly always appears to be awaiting someone’s approval.

Underlying all this is the weirdness of seeing a very American story enacted by a largely Australian cast, including Richard Roxburgh, David Wenham and Kodi Smit-McPhee (aside from the leads, the key exceptions are actors playing African-American characters, such as Kelvin Harrison jnr as B.B. King).

Clearly, authentic casting wasn’t a top priority. But then, the idea that authenticity and phoniness are two sides of the same coin may be part of what Baz, the people’s postmodernist, has been trying to tell us all along.

That would be one way to interpret the perverse insistence on having Elvis share the spotlight with his shifty mentor, from the moment they lock eyes in a literal hall of mirrors to the Star Wars-style climax where the Colonel explains that deep down they’re the same: “Two odd, lonely children reaching for eternity.”

“Reaching”, certainly, is the word.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article