By Robert Moran

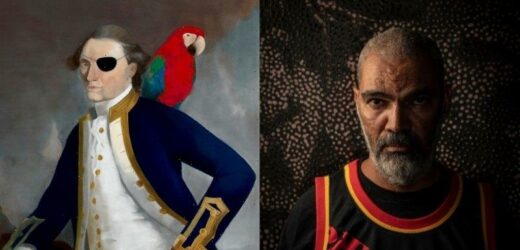

Daniel Boyd::” Sometimes I feel it’s a bit of a burden having to be the person to continually share that experience with other people, but I feel it’s my duty to help my people as well..”Credit:Wolter Peeters

In his small art studio, nestled in one of Marrickville’s industrial strips in a winding complex shared with fellow artists, prop sellers and, I think, a butcher, Daniel Boyd, wearing an Atlanta Hawks jersey, is pointing at some beams in the ceiling.

Above the rusty walls where his newly completed canvases hang – paintings of Angela Davis, Muhammad Ali, and his late mother, all partly obscured by his recurring design element, those signature “lens” – he’s pondering installing a basketball hoop. “See that panel there? I’ll put it on the back of that, and just kind of turn it around whenever I wanna shoot hoops,” he says, quietly giggling to himself. Art and basketball, aligned in one idyllic space. I’ve dreamt of a place like this.

In the early ’00s, before he was one of Australia’s most celebrated contemporary artists, Boyd, soft-spoken and thoughtful but with an arresting intensity, was a semi-pro baller playing for the Cairns Marlins in the ABA, the NBL’s then second-tier league. A compact 6ft,1in shooting guard, he counted NBA veteran and Boomer Aron Baynes among his teammates. “Yeah, that was a big part of my growing up. I had dreams of playing in the NBA and stuff,” he recalls. “But I just, kind of, moved away from basketball.”

Two decades on from his hoop dreams, 39-year-old Boyd is preparing for what will be his first major Australian solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW. It’s called Treasure Island, but it could be called The Everlong History of White Delusion in Australia. The exhibition features more than 80 works from across Boyd’s 20-odd year career, works that interrogate Australia’s colonial legacy and entrenched Euro-centric narratives, and the way history is distorted and erased.

Originally from Cairns, Boyd is a Kudjala, Ghungalu, Wangerriburra, Wakka Wakka, Gubbi Gubbi, Kuku Yalanji, Yuggera and Bundjalung man with ni-Vanuatu background from his father’s side. His early forays into art were attempts at reconnecting with a heritage that had long been excised.

“I’m first generation out of a mission. Yarrabah. It was an Anglican mission. My ancestors were all taken from parts of Queensland, stolen from their parents. They were forced to sever any form of cultural inheritance, of language or any cultural lineage. You were punished if you spoke your language. Their movements were controlled. They weren’t allowed to leave the mission without a permission slip that the government would track.

“It was very suppressive,” Boyd says. “And so, like, I don’t have any connection to my languages. It kind of meant that I just always felt there was something missing, you know? When I got to university, I was trying to make sense of all that and where I fit because my parents were very affected by these actions that the government and the state and the church were enacting upon my people.”

The exhibition takes its title from one of Boyd’s earliest works, completed when he was a 23-year-old art student at the Australian National University. His No Beard series includes re-appropriated neoclassical portraits of colonial heroes like Joseph Banks with a simple edit that foregrounds his Indigenous perspective towards their exploits and, essentially, Australia’s established history: eye patches added to reframe them as pirates.

Daniel Boyd’s Sir No Beard, 2007.

“Walter Benjamin wrote about the angel walking backwards, seeing the past but kind of walking into the future. It’s a similar kind of thing, you know?” Boyd says of the works. “We have to know where we’ve come from to understand where we’re going and not make the same mistakes we made in the past. Sometimes I feel it’s a bit of a burden having to be the person to continually share that experience with other people, but I feel it’s my duty to help my people as well.”

The No Beard works, reframing Australia’s “discovery” as a Defoe-esque world of plundering colonial pirates, show Boyd’s satirical, subversive bent. On YouTube there’s an old video of the young artist talking through his work We Call Them Pirates Out Here with a sly deadpan, explaining the inclusion of his housemate and his sister’s boyfriend in the painting on the side of the pirates’ gang: it’s a personal touch, but also a wider note to white audiences to confront their own complicity in Australia’s original sin, denying the chance to let themselves off the hook, so to speak.

Daniel Boyd’s We Call Them Pirates Out Here, 2006.

“Satire was a big part of that. I was trying to subversively tell a story without being immediately denied that opportunity,” Boyd explains. “But, like, you benefit from the wealth and capital made from taking land. You have to acknowledge those things and how you benefit from it.”

Boyd’s subsequent work marked a dramatic departure from such colonial remixes to his current technique, defined by the use of lenses – sometimes paint, glue or metallics – affixed to his paintings to distort a work or partially obscure the full picture. “I had more questions, and the visual language that I’d created for those No Beard works, I felt like it had run its course,” says Boyd. “It wasn’t able to allow all these other things that I was interested in to kind of come through that language. Painting a picture of, like, my mother and I. I wouldn’t be able to situate it within that kind of conceptual framing of those No Beard works.”

Although stylistically different, the lens function in the same thematic space as his No Beard paintings. Boyd says he was inspired by Martinique philosopher Edouard Glissant’s theory of opacity, the idea that multiple perspectives exist simultaneously. It offered another way of critiquing and challenging the established dominance of Western colonialist and imperialist narratives.

“Glissant, he has this quote where he says, ‘The experience of the abyss exists inside and outside of the abyss.’ You can’t have one without the other, they’re the same thing. So this idea of the unknown, of memory, experience, and the denial or control of information, it’s all a part of it. What you see is not the whole story,” Boyd says. “And so those works, I don’t see them as too different. To me, it is the same thing.”

Daniel Boyd’s Untitled (PW), oil, pastel and archival glue on canvas. The painting, highlighting Boyd’s signature lens work, won him the Bulgari Art Award in 2014.Credit:Art Gallery of New South Wales

Boyd’s stylistic shift was not without its discomfiting wrinkles. Being an Indigenous artist, and because of the technique’s visual reliance on those dot-like lenses, viewers and critics assumed Boyd was referencing Aboriginal dot painting, the prominent central desert art movement of the late ’70s. As Boyd has repeatedly said, dot painting had nothing to do with it. Like No Beard, it almost seems a subversive ruse, to force the viewer to confront their own racist bias. Boyd says it didn’t even cross his mind until he saw that was how people engaged with the works.

“I’d started making these [lens] works when I was thinking about the effect that Christianity had on, like, the denial of my cultural inheritance. I was using these illuminated manuscripts and hole-punching them, but then taking the holes and, like, putting them on a separate page. But then, you know, people see the work and go, ‘Well, he’s Aboriginal, so this is part of that tradition…’ But it’s not. It’s about perception, about how you see things or understand things.

“It became more present afterwards when I understood how people were projecting onto these particular works. It was like, ‘Oh, this is how they’re talking about it?’ I mean, even now I’ll tell people that it doesn’t have anything to do with the work that came out of Central Australia, and they’ll go away and write that it does anyway! It’s fascinating to me.”

Around Boyd’s studio, circling a wooden bench where a stack of early ambient vinyl and a book titled Escape to Tahiti lies open, hang a number of new pieces that employ his now-signature technique: a painting of his mother, who passed away last year at 65 from motor neurone disease (“It’s a way for her to be present. I mean, she’s always present, but it’s, like, another tool to speak about that relationship to where you come from”); of Matisse (“That one’s about modernism. It’s kind of in opposition to modernism in all its, like, singularity”); of the Queen and former president of Ghana Kwame Nkrumah seated at a formal dinner, pictured when Ghana gained independence from the British (“She was trying to convince Kwame Nkrumah not to leave,” Boyd says with a laugh).

There’s a painting of Muhammad Ali at the Aboriginal Legal Service in Redfern, that speaks to the shared civil rights movements between African-Americans and Australian Aboriginals, particularly in Sydney. Another work parallels the Occupation of Alcatraz by Native American protesters in 1969-1971 with the local protests for sovereign rights that happened during the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy in 1972.

Boyd in his Marrickville studio. His painting of Angela Davis in the background speaks to the shared struggle of Black populations across the globe.Credit:Wolter Peeters

Some of these works will go to the prominent Kukje Gallery in Seoul in Korea where Boyd has previously exhibited, others to the US for a coming group show in Los Angeles. Boyd’s international pull shows the extent to which his themes are relatable to, and speak to the shared struggle of, colonised peoples around the globe.

It’s perhaps most notable in the way his No Beard series prefaced conversations that were brought to mainstream attention during the Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd in June 2020, that same righteous energy that saw colonial statues tumbling to the ground from the US to the UK. As someone who was placing pirate patches on colonial figures for more than a decade already, Boyd’s work seemed to anticipate the moment. So, what’s his take on the ever-divisive statue debate in Australia?

Boyd laughs. “I think it’s whatever people feel like doing, you know? In India, they have, like, a graveyard of colonial statues. It’s like, okay, all the cultures we have in this country that have been oppressed by imperialist expansion, and you have all these signposts out in public? They need to be moved from the public space. And if someone wants to go see them, they can go and see them in private, like in a museum.”

Must say, I’m surprised by his answer. Obviously, those images of the NSW Police force forming a protective circle around a statue of Captain Cook at Sydney’s Hyde Park were absurd, but what about leaving the statues up and just allowing them to be publicly defaced as a regular reminder of Australia’s skewed history? A Boyd-ian pirate patch on every public statue of a coloniser would be a beautiful thing, no?

Boyd laughs again. “Well, it’s not like one way is the only way. It’s a complex thing to reassess nationhood and imperialism.”

He has a point. You also can’t deny that viral video of the group in Bristol, England, cooperating with such efficiency to pull down a statue of slave trader Edward Colston and sending it rolling into the local bay.

Daniel Boyd’s Untitled (PI3), 2013, oil and archival glue on linen.

“I actually have that in my catalogue, in the exhibition,” Boyd giggles. “I remember my kids cheering at home, you know? ’Cause slavery is a part of my ancestry.” Boyd’s great, great paternal grandfather was brought from Pentecost Island in Vanuatu to the sugarcane fields in Queensland as a slave; he referenced the personal history in his haunting Untitled (PW), which earned him the Bulgari Art Award in 2014. “Capital built on the backs of free labour is a part of Australian history, and it needs to be acknowledged.”

Recently, Boyd’s turned his attention to the built environment. He designed the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander War Memorial in Canberra, and is currently working on a public plaza at the Circular Quay end of George Street with famed British-Ghanaian architect Sir David Adjaye that will see his lens-work dot a canopy over the space, which is set to open this year. Last month he also unveiled a work in the Archibalds, a portrait of Mount Druitt hip-hop group OneFour.

And, of course, there’s also the hoops. I proffer my apologies to Boyd for interrupting the artist in his private workspace during his brief morning respite right in the middle of the NBA playoffs (unfortunately for him, Boyd’s a Lakers guy). To be honest, I’m surprised he didn’t just have NBA League Pass streaming all day there. “Oh, I do,” he laughs. “I project it on the wall over there.”

He doesn’t ball anymore. But his daughters, aged 11, 8, 4, recently started playing basketball for the Redfern All Blacks. “I kind of got – I wouldn’t say roped in but, like, I was very present, so they asked me to coach the Under-14 girls team. So I’m coaching now,” he laughs.

He has no claims to be the next Gregg Popovich; life as one of our most significant artists is enough. “I don’t have a clipboard or anything like that,” Boyd jokes. “I just call timeouts and sub them in every now and then. They’re just having fun, you know? And I’m just there to keep them going.”

Daniel Boyd: Treasure Island opens at the Art Gallery of NSW on June 4.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article