Save articles for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them any time.

I’ve joined a cult. That’s the only explanation for it. Thousands have gathered on the steps of the cathedral, in a heady mix of ecstasy and fear, stripping off their clothes to face the cold air of a Sunday morning that should be spent hiding under a quilt.

Someone, almost certainly an enemy of mine, decided some months ago that it would be a fun idea to sign up for a half-marathon. Challenge yourself, this beast thought, as if that doesn’t sound awful. I don’t want to know my limitations. I’d rather ignorantly believe I have no limitations. I would like to watch the Olympics every four years confident I could at least take bronze in a sport I’ve never heard of before had I actually tried.

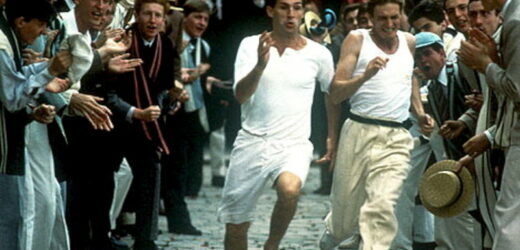

Cue the Vangelis: joining a half-marathon was a terrible mistake.

Like all peak-performing athletes, I made sure to fill up on a nutritious and scientifically balanced ham and cheese croissant, perfectly designed to keep a couple of flakes in the back of my throat for the entirety of the run. I stood in the herding pen awaiting our allotted start time and listened to the deafening silence that followed a hyped-up announcer shouting “Are we ready!?” over the PA system. Then, we were off. A hypothetical bad idea was suddenly transformed into an ongoing mistake.

I quickly found my natural place within the horde, slotting nicely ahead of the people who run in costumes but behind the men who feel comfortable running shirtless, and began my usual form of motivation. I’ve never been one for positive visualisation because to me, it is ridiculous to think that a nice thing might happen. My preferred method is a pioneering form of negative-visualisation. At the start of the race, I tell myself that I owe the devil 21 kilometres. I am not a grand champion undergoing some great feat. I am in the comeuppance section of a Faustian bargain. At the very least, this explains all the suffering.

As a lifetime exercise agnostic, I had always believed that, at some point, when you get good at it, every moment becomes easy and pleasurable. Slowly, I had realised this wasn’t the case. Pain doesn’t go away, you just get used to it. There was an oddly positive atmosphere among the runners. We were not racing against each other (indeed, I think we were starting at somewhere around 8000th place); instead we were all going on innately personal journeys, side by side. Together, we found out we weren’t the only ones who thought it was somehow fun or good or worthwhile to pay money to undergo something so awful in our own free time.

Somewhere around the eighth kilometre, I start thinking about how the process of running a long distance like this takes a similar form to any creative endeavour. The hardest part is starting, the second-hardest part is to keep going, a process that is not a single decision but rather a constant battle against the knowledge that it would be easy to simply quit and walk away. To continue offers only more pain. Satisfaction arrives only upon completion. As the constantly misattributed saying goes, “I don’t like to write, I only enjoy having written”.

This is the first sign that dehydration is really starting to get to me. Ooh, look at Murakami over here. He’s penning a novel with his thick thighs slowly trudging along the harbour. Whatever he’s writing is surely a tragedy. A slow and lumbering battle against nature and human limitation, borderline Russian in its bleak outlook.

Soon, I owed the devil only 10, or even five kilometres. These numbers felt possible. Perhaps I was an athletic Adonis after all. Never mind that I’d just been passed by a woman who was conservatively somewhere between 30 and 40 years older than me. She was probably a modern-day Hermes or something. Not my problem. Between moments of pain and regret, I began to feel this strange little thing I’ve coined “happiness”. There were bits of this experience that I had to begrudgingly admit were enjoyable. It was nice to see a city I’ve lived in for decades from an entirely new perspective. There was something rebellious about running down the middle of a highway in broad daylight (between clearly marked cones, on a route organised years in advance, under police watch, and with all proper permits, you know – rebellion!).

‘Ooh, look at Murakami over here. He’s penning a novel with his thick thighs slowly trudging along the harbour.’

The final kilometres were a walk in the park. I mean this purely literally. They were a hellish stumble through the botanical gardens. But somewhere in those grounds a beautiful transformation occurred, where suddenly it felt as if this race would not be something that killed me but rather something that would change me. I was no longer an outsider in a foreign community of weirdos. I was one of the weirdos! I’d become part of the shuffling horde.

Here’s something that doctors won’t tell you: it turns out training and preparation pays off. Slowly I realised that not only could I do this, I was actually going to do it. More than that, it was mostly done. I began feeling something in my chest that I immediately diagnosed as a massive heart attack but later re-categorised as pride(!?). As I crossed that finish line, I felt the urge to let out a primal scream. Luckily for myself and the people around me, I didn’t have the energy for anything of the sort and instead just shuffled over the line. I’d finished the half-marathon. I’d shown what you could half-achieve when you set half your mind to it.

Now, the park has been transformed into a scene from Saving Private Ryan. Bodies strewn everywhere, groans of pain, the nursing of wounds. But somehow, it was beautiful. It was the most positive atmosphere I’d ever felt. Everyone was so proud of themselves, of their friends and family. They were celebrating a great achievement. I spoke with a few of the participants, one who had an eight-month-old at home and somehow wasn’t constantly tired enough, another who used the event as a milestone of injury recovery.

Their smiling faces, friendly attitude and burning sense of accomplishment filled my heart with joy as I knew, once and for all, that I would rather die than ever, ever do this again. Oh my God, I cannot move. What the hell? Oh my God.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

Find out the next TV, streaming series and movies to add to your must-sees. Get The Watchlist delivered every Thursday.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article