How the nanny wars got nasty: Never mind empty shelves and the petrol crisis… suddenly it’s child carers who are in short supply

- Number of nannies coming to the UK has fallen to almost zero since pandemic

- Owner of an agency in South-West London, says mothers are poaching nannies

- Families and agencies are starting to go to court over breach of contract

- It now costs £46,000 on average to hire a nanny in South West London

Covert ‘cappuccino meetings’ are the usual starting point. Then follows a flurry of sly, seductive emails before the offers start rolling in.

These include higher wages or perhaps a cash-in-hand deal; designer cast-offs from Mum’s wardrobe; an upgraded apartment, even. The sort of super-luxe lifestyle a girl can only dream of . . .

Across the country, nanny theft is on the rise. Just like HGV drivers or fruit pickers, as we enter the pre-Christmas flurry of family events and school concerts, there’s an acute shortage of childcare workers, which means a good nanny — always a prized possession — is now a seriously fought-over asset. The problem is Covid, of course, with a side order of Brexit.

Travel bans from countries such as Australia and New Zealand mean the number of nannies coming to the UK has fallen to almost zero, while European au pairs, keen to get back to their families as soon as the pandemic struck, are finding new visa requirements make it harder to return. While everyone worked from home, parents muddled through — but the return to the office has created a perfect storm. Just as mums need childcare, there’s none to be found.

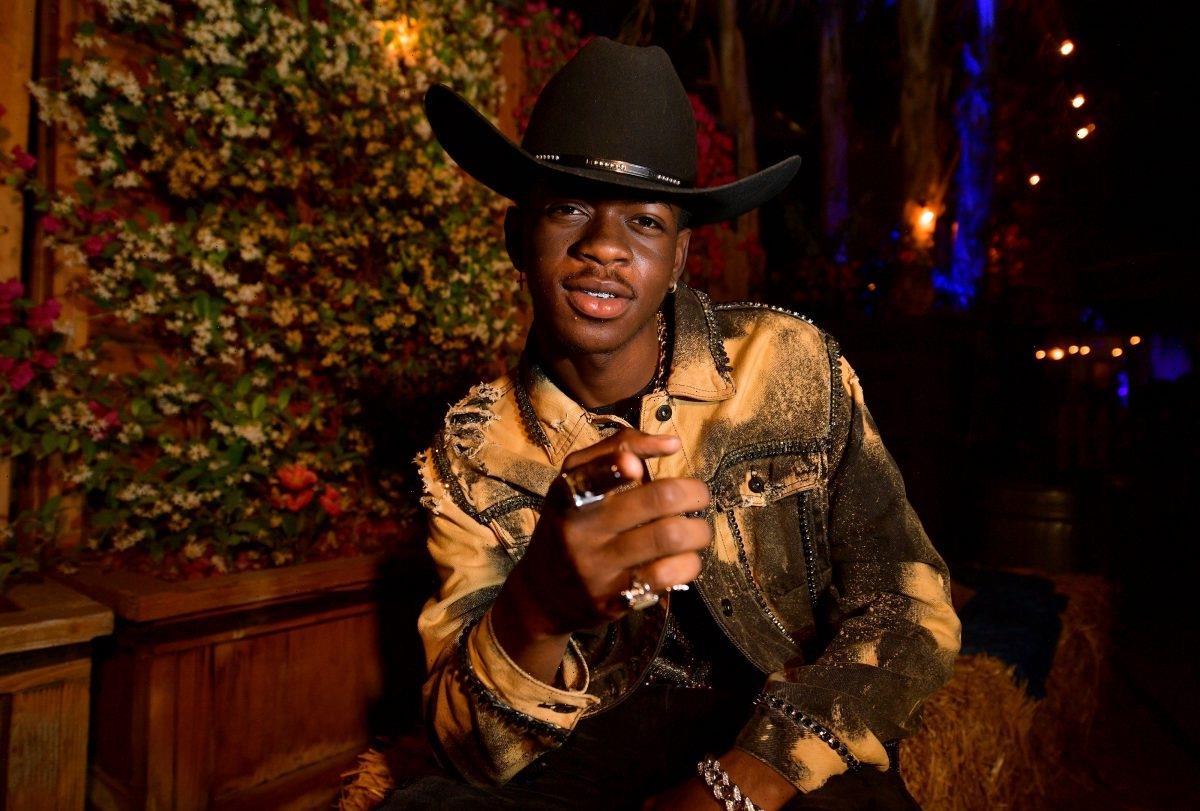

As the number of nannies coming to the UK falls, the owner of an agency in South-West London reveals families are resorting to nanny poaching. Pictured: Emma Elms, who has had 16 nannies, with her last nanny, Talia, far right

Nowhere is this more evident than in leafy South-West London, where I’ve run a nanny agency for the past ten years.

Here, mothers are resorting to nanny poaching to such an extent that families and agencies are starting to go to court over it for breach of contract.

In fact, we’re preparing a court case right now. One of our clients, a lawyer, used one of our nannies for a few months to help the family during a tricky patch. She then said she’d terminated the contract, but continued to use the nanny on the QT at a lower rate (for her — we didn’t get our cut).

That ended when the nanny got fed up with the way she was treated by the children and forwarded us the emails outlining this private arrangement, stitched up behind the agency’s back, which resulted in us starting legal proceedings against the family for breach of contract.

With nannies so scarce, selfish mums are also pinching nursery nurses. Recently, I heard how two mothers, who both loved the key worker at their children’s nursery, discussed between them how to poach her, only for one of them to dive in suddenly and do it unilaterally.

The nursery worker was offered a huge amount to go and work for her exclusively — to the absolute disgust of the other mum, who previously had been the first mother’s best local friend.

(Karma prevailed, however — the new employer turned out to spend most of the day in bed, and the poached nursery nurse, fed up with doing everything, eventually called the other mum and went to work for her instead.)

Another mum spotted a friend’s nanny at a birthday party — they’re happening again now — and loved how she was with her child. She sidled up to her between rounds of pass the parcel, plied her with fizz and said she’d do anything to acquire her services.

Pre-Covid, you could get a decent nanny for about £32,000 to £35,000 per year, but now it costs an eye-watering £46,000 on average to hire a nanny in South-West London

Luckily, the nanny had heard stories (all nannies talk) and knew the grass definitely wasn’t greener, so said a polite but firm no.

Like energy bills, childcare wages have been surging — and desperate working mums are paying the price.

It used to be expensive to hire a nanny, but since the pandemic, wages are in another league.

Pre-Covid, you could get a decent nanny for about £32,000 to £35,000 per year, but now it costs an eye-watering £46,000 on average to hire a nanny in South-West London. Great news for young women who want to earn good money early.

In North-West England, it’s at least £32,500, an increase of 11 per cent year-on-year, while across the UK in general it’s almost £30,000 for a live-out nanny.

The UK is effectively catching up on pre-Covid salaries that once applied only to London. (In London’s super-rich neighbourhoods, such as Holland Park, it’s normal to pay a 23-year-old nanny £65,000 plus a £3,000 bonus. Not forgetting the expected perks: holidays by private jet, a personal apartment and a top-of-the-range car for the school run.)

Meanwhile au pairs, once the saviours of cash-strapped, juggling working mums, are virtually non-existent.

Up to 90 per cent of all au pairs come from Europe, and since the end of free movement, with childcare workers categorised as ‘skilled workers’ who must earn at least £20,480 a year to enter the UK, it’s all but impossible for them to come.

In order to hang onto nannies, some mums are creating housekeeper jobs — bumping up the childcare hours with ironing and cooking (file image)

Au pairs, after all, traditionally received board and lodging and perhaps £100 pocket money while they helped out and learned English.

Even if you can get one, they can be hard to keep.

One single mum living in Surrey recently had a new 19-year-old French au pair who was quite high-maintenance and struggling to fit into family life.

Two weeks into the role, after a particularly bad day with the child, she went to the house of a neighbour who was a friend of her boss, and burst into tears.

Instead of counselling her on how to cope with British family life, the mum — who had been receiving help with the school run from the au pair — offered her the opportunity to move into her home and au pair for her family instead. So she did. That very day.

Childcare is evolving in other ways, and Covid has also changed the requests we get at the agency.

‘After-school nannies’ are at a premium and represent the number one ask we get from working mums.

It sounds simple — pick up the kids after school, take them home for tea and homework and finish when mum breezes in from work at 6pm (or more often 8pm from the wine bar).

But now that nannies are in such short supply, they just won’t work for odd hours here and there. In order to hang onto them, some mums are creating housekeeper jobs — bumping up the childcare hours with ironing and cooking. One mum even asked her nanny to paint the house when the family was on holiday.

Some mums are so paranoid about losing their nanny that, when their child goes off to school, they pay to keep them on for the whole day (file image)

Some mums are so paranoid about losing their nanny that, when their child goes off to school, they pay to keep them on for the whole day, doing not very much.

Young nannies can set their terms out, too, these days. One of ours was asked to sleep in the same bed as her four-year-old charge because the high-flying mother could not, under any circumstances, lose her sleep.

Although it was against the terms of her contract, the young nanny was so desperate to hang on to her job that she did whatever it took.

Not so any more. Few nannies want to be a paid servant — they’ve usually trained hard at college to be a specialist child carer. It’s much easier to say no to over-demanding employers or odd requests.

The key challenge for working mums right now is that, however much you pay them, keeping a good nanny can be out of your control.

The number one reason a nanny leaves is because of the appalling behaviour of the kids they’re looking after.

It’s quite common for children to kick and scream at nannies, jump on the table, throw things at them and ignore everything they say. Then Mum gets home and brushes it under the carpet, saying they must have been ‘a bit tired’ that day.

One of our girls looked after a child who was totally vile. She made the nanny cry every day. The dad was shocked by reports of the child’s terrible behaviour and tried to take responsibility, but the mother just laughed it off.

Even if it was true, it was inconvenient — she didn’t have time to think about it: she had to work!

The number one reason a nanny leaves is because of the appalling behaviour of the kids they’re looking after, with children kicking and screaming at nannies (file image)

Today, I’d advise that nanny to walk out — she’ll get another job in an instant. Ditto the poor nanny who had to arrive at 5.30 every morning so that Mum could go to yoga at her exclusive gym.

Another good thing about the current nanny crisis is the end of the simply sexist practice of picking a nanny based on looks. Yes, that really happened.

Many mums, heavily influenced by the father, would say they wanted a good-looking, young Australian, New Zealander or South African: someone who would look great around the house and complement their lifestyle.

Other, more insecure mothers wanted a girl who wasn’t so beautiful.

I had several who asked for pictures in advance before interviewing a nanny, and when we sent one client a CV with a picture of a gorgeous and very qualified Swedish nanny, she asked for more options.

She ended up hiring a more ordinary-looking, less-qualified young woman.

On another occasion, one larger nanny wasn’t hired for the job because the client thought she didn’t look fit enough to climb the five flights of stairs in their home. Pre-Covid, some chose nannies with cut-glass English accents because they wanted their child to ‘speak well’.

With more requests for nannies than available, the choice we once offered clients has all but gone.

Even if you are lucky enough to find one, it might mean remortgaging to pay her salary.

I’ve gone through sixteen nannies… and counting

By Emma Elms

Over 13 years of motherhood, with daughters now aged four, nine and 13, I have got through 16 nannies. I know — I’ve thought it, too: is it . . .me?

Well, quite possibly. But the truth is, all mothers will secretly admit that finding exactly the right help is a task of gargantuan difficulty. Which is why I look around at the current nanny options, and the gaping post-Covid shortage, with even greater trepidation than usual.

Until recently, I was the lucky employer of Talia, nanny number 16, and by far the best I’ve ever had.

The only person I’ve ever given Talia’s number to is my best friend, for an evening’s babysitting, and then only because I know for a fact she’s happy being a stay-at-home mum and doesn’t need day-care.

Emma Elms said one of her early nannies sealed her fate when she chose to sit in McDonald’s for an hour with her first baby, Amelie, who came back smelling of fries. Pictured: Emma with her last nanny, Talia, far right

My other nannies have varied dramatically in quality and approach over the years, from Tina, who once, to my great alarm, allowed three-year-old Amelie and her friend, Claire, to empty an entire bookcase and pile up the books into a teetering Tower of Pisa; to the beautiful Swedish blonde Marisa, who was a natural with babies, but sadly only had two hours of availability a day, starting at 8am (ouch).

The best nannies are always on full-time contracts with high-earning power couples.

One of my early recruits sealed her fate when she chose to sit in McDonald’s for an hour with my first baby, Amelie, whose hair and babygrow came back smelling strongly of fries.

Then came Judita, a grade A nanny shared with another parent on my street. Nanny-pooling is a great way to reduce the cost, but Judita’s brilliance was ruined by her faithful companion — a growling Alsatian that belonged to the other mum.

Almost all my nannies have been non-Brits, which makes me even more anxious about my current quest for nanny number 17, just as Covid and Brexit conspire to make it harder than ever to find one.

The fact is, I’m still in love with Talia — possibly my partner is, too — but now my youngest has started school, I really need a nanny/housekeeper-in-one who will come to our home, cook the kids’ dinner and maybe even tackle the mountain of Barbies invading the lounge.

So . . . believe it or not, I’m on the hunt again.

This time, hearing from friends how hard it is to find the usual European or Aussie nannies from agency or online sources, I tried a different tactic and tapped up a teacher at my daughters’ school for ideas.

Emma said almost all her nannies have been non-Brits, which makes her even more anxious about her current quest for nanny number 17

Now — whisper this, I don’t want everyone to have the same idea — I have three of her friends lined up to interview, all mature, 50-plus British women.

It’s not the first time I’ve gone down the teacher route. Aged two, Amelie started attending half-days in a lovely Montessori nursery, and I seized the opportunity to top up my childcare with their staff, recruiting Cara (a kind-faced, 30-something who clearly adored Amelie) and Katia (a glamorous blonde West Londoner).

I clicked with both immediately and attempted multiple bookings with each, but they soon left the world of nursery care for better paid pursuits.

Next came Maria, a calm, confident but startlingly business-like South African of precisely the kind that are so hard to find now.

She stayed with me for over a year — at the time, my personal best!

But I grew a little nervous when she kept insisting I sign an insurance disclaimer that if anything happened to Amelie, I wasn’t to sue her. I decided it best not to sign.

She quit to leave London and start a family with her husband (and I’ll bet she’s not signing any disclaimers of her own).

While searching for The One again in 2011, after the birth of my second daughter, Fifi, a lawyer friend offered to ‘share’ her fun nanny, Lou, who had a baby son, looked after by her female partner.

Full of energy and life, I thought Lou would be the perfect person, but after a while my friend grumbled her house was full of unwashed dishes and wet swim kit left to fester. and switched to a live-in au pair.

In my mobile I have the numbers of two other nannies — Charlie and Gosia, whom I briefly used, but all I can recall is that they were young, pretty, Eastern European and always booked up.

So, I was overjoyed finally to find my Mary Poppins. Talia was a warm, kind, funny, loving, reliable and efficient Romanian mother-of-two, who lives right next door.

She was by my side when I brought home my third daughter, Belle, and it was Talia upon whom I relied to keep my domestic life running smoothly while I juggled with work during lockdown.

Now that Talia looks after children in her home and I want her at mine, it’s time to look anew. Wish me luck.

- SOME names have been changed.

Source: Read Full Article