Though regarded by cinephiles as one of the architects of the “New Hollywood” largely because of moody character studies like 1970’s “Five Easy Pieces,” filmmaker Bob Rafelson — who died Saturday at 89 — will also always be adored for his co-creation and production of the decidedly less moody, madcap television series “The Monkees,” and for further directing that makeshift band in the comically avant-garde 1968 film “Head.”

Rafelson is very fondly remembered by vocalist and drummer Micky Dolenz, the final surviving member of the Monkees, who shared his thoughts about Rafelson’s role in the creation and development of the group with Variety.

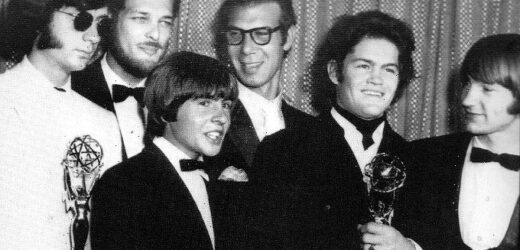

A wildly silly sitcom about a faux teeny-bop band meant that its producer-showrunners, Rafelson and Bert Schneider (who died in 2011), had to find a willing quartet of actor-musicians. Enter Davy Jones, Peter Tork, Michael Nesmith and Dolenz, who became the Monkees, recorded a dozen hits selling over 75 million records worldwide, and turned network television on its ear with their Marx Brothers-like sensibilities during two seasons on network TV in 1966-68. (Rafelson is pictured at center in the photo above, along with, l-r, Tork; Dolenz, Jones, Schneider and Nesmith.)

Dolenz got on the phone Sunday night to recall his experiences with the filmmaker who brought the Monkees to the world — and with them, an improvisational spirit that soon came to be part of his more dramatic features as one of the innovators of the New Hollywood. Before Rafelson died, Dolenz says, “I did get a chance to send him a message telling him how eternally grateful I was that he saw something in me.”

You had a career as an actor before you got to “The Monkees.” How did you wind up before Bob Rafelson in the first place?

I was going to college at L.A. Trade Tech, studying to be an architect. I had already been in the business since I was a kid, and after high school, I thought that maybe I should get serious, and get a real job. Even though I was into the idea of building, I was still doing some acting on the side.

You did guest shots on “Peyton Place,” “Playhouse 90” and “Mr. Novak,” after you were a series regular on “Circus Boy” in the late ’50s.

Shows like that, very much of the time. So, I’m going up for shows. I had an agent. And he sent me something on this pop music situation comedy. I knew it was a series, and what it entailed, but I also knew that 99 times out of 100, you don’t get the gigs, and if you did, it might not even go to pilot, let alone sold. I was no fool.

But you knew the power of a television series.

Yes. And what’s funny was, at that same time, I was up for like three or four of these “young pop” music series. It was in the air. Besides “The Monkees,” there was “The Happeners.” That was about a Peter, Paul & Mary-like group. It did go to pilot, but did not sell. There was one about a surfing band, like the Beach Boys. That didn’t go to pilot. The other one was based on those large-scale folk ensembles such as the New Christy Minstrels with 20 pieces. That didn’t go to pilot. Then there was Rafelson’s “Monkees.”

Could you tell the difference between, say, “The Happeners” and what Rafelson and Schneider were trying to do?

Immediately. For instance, I remember walking into the studio and there’s Bob and Burt. They were about the same age, late 20s, early 30s. They had on jeans and T-shirts, were drinking coffee and eating pizza. They weren’t much older than me, and didn’t look at all like traditional Hollywood producers of the time who wore suits and smoked cigars. That was different. Then the first audition, reading some sides from the pilot – which happened to be called “The Monkeys”; I still have the pilot script – and that interview was laid-back and spontaneous. They were part of the youth culture themselves. This was them. They were majorly into the Beatles. But Rafelson’s idea for the show predated “A Hard Day’s Night.” Bob apparently had been a roadie for a band before he got into directing, and he thought that those experiences would make for a great series.

The British Invasion and the rush of California pop and surf hits just pushed the notion into a mainstream viewing audience’s consciousness.

Definitely. So I did the interview with Bob and Burt, went back to school, got a call back for another interview where I had to sing and play – that was a necessity, even to just get into the audition – then went in for a few more off-the-cuff auditions… We used the set of “The Farmer’s Daughter” for those… and several weeks later got the call that the pilot was mine. We did the pilot in San Diego, then waited for the pilot to sell.

The “Monkees” pilot very nearly did not get sold, right?

That’s true. That is, until Bob and Bert, the brains of the operation, rejiggered it. Made it looser. I get the sense that Bob was the creative part of the partnership, with Bert being the business guy. Bert’s dad was a head at Columbia Pictures (Abraham Schneider, who headed the Colpix Records and Screen Gems Television units of Columbia) so that helped. Plus, Jackie Cooper was in the mix, as a head at Screen Gems. I was a big fan of his, and identified with him because he too started out as a child actor. Jackie ordered the pilot. But Bob was always the one that I looked to for the creative input, the vision. He directed many of the episodes, along with James Frawley. Between the two of them, they crafted the tone and the shape of the show and all of the innovations.

Like Rafelson’s insistence on improvisation?

Yes. I had never improvised before that. You couldn’t improvise a television script. You’d be fired. Imagine going on set at “Peyton Place,” not knowing my lines, and just making it all up. Wing it. Rafelson, however, encouraged us, trained us to improvise. James Frawley, too, as he was out of Second City with Elaine May and Mike Nichols, pushed us into improvisation. It took me a minute to get used to improvising. Mike (Nesmith), though, he was great at it straight away. That off-the-cuff thing is probably what steered them into producing “Easy Rider” (1969, uncredited) and “Five Easy Pieces,” along with “Head.”

“Head” is such a cinematic, psychedelic free-for-all.

Such a crazy movie. Definitely weird at times. And it’s become a hell of a cult thing. Quentin Tarantino told me it was in his top five favorite films. Edgar Wright, too. Bob and Bert – along with Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda, Martin Scorsese and Peter Bogdanovich – turned the movie industry on its head. Before them, you couldn’t get a movie made unless it was through a major studio.

Now, I’m not always sure what “Head” was about, but I have a theory. Do you remember the scene where Mike, Teri Garr and I are doing this Western scene within the film, and I’m getting arrows fired at me by Indians?

Who would forget it?

Well, in that scene, I got hit by four fake arrows. Then I stand up, yank the arrows out of my chest and yell “Bob. I’m fed up. I’m not going to do this anymore.” Then I bust through the scrim into another set, and walk out. That, to me, is metaphorical about what the movie is about and what they were about — busting through the old school, traditional Hollywood system. That was Bob. Busting down the old ways for something new. He helped tear down the walls to essentially almost single-handedly create a new independent Hollywood film industry.

So what was Rafelson’s strong suit as a creator and director on “The Monkees”?

Bob encouraged us to be ourselves. They did not want to hire four actors to play parts they made up. They wanted four different people with different energies and spirit, yet who had compatibility and charisma. Producers want that vibe — “Friends” had it, for instance. They wanted guys who could sing, play and be spontaneous. And be happy to do that. Look, there were times where we so excited, it got out of hand. They had to shut down the set because the four of us were bouncing off the walls, and they were encouraging it. Bob had some real chaos to control, but he made it happen and made it work.

Read More About:

Source: Read Full Article