There can be few exhibitions in Australia that have shocked viewers as thoroughly as Peter Booth’s show at Melbourne’s Pinacotheca Gallery in late 1977. The most telling comparison might be with American painter Philip Guston, whose 1970 show at Marlborough Galleries, New York, was greeted with scorn by leading critics including Robert Hughes. In both instances, an artist who had made his reputation as an abstract painter turned suddenly and dramatically to figuration.

Guston’s new works were cartoonish social satires, filled with images of oafish Ku Klux Klansmen. These works are now viewed as landmarks in modern art’s reacceptance of figuration after so many years of believing abstract painting was inherently “progressive”. The provocative nature of Guston’s Klansmen was proven for a second time recently when four major American museums decided to postpone a 2020 retrospective because they felt this imagery might be misinterpreted as an affront to “racial justice”.

Peter Booth in 2015.Credit:Jason South

In the United States, it seems paternalism and paranoia have reached the point where museums can’t take the chance that critiques of injustice might be accidentally seen as celebrations. It’s a bit like worrying that Goya’s The Third of May 1808 might be interpreted as an incitement to violence against Latinos.

Booth’s turn to figuration took a different path. Although the artist admits to being perpetually disturbed by “the times we’re living in”, his paintings have never been overtly political. He is neither a social commentator, a cynic nor a satirist. The realm Booth’s work explores is that of dreams – or, given the nature of his imagery – nightmares.

A survey at the TarraWarra Museum of Art in the Yarra Valley, curated by Anthony Fitzpatrick, takes us from one of Booth’s obdurate early abstracts of 1974 – flat vertical slabs of black paint known as doorways – through to more expressive works, on to the nightmare paintings, and then a powerful mixture of landscapes, figure studies and crowd scenes. What’s ultimately so impressive is Booth’s ability to imbue his smallest drawings or most lyrical landscapes with a sense of mystery, and often dread. Looking at a wintry landscape devoid of people, we feel they are lurking somewhere out of frame. A tropical jungle such as Painting 2022, which might have won the admiration of the Douanier Rousseau, is inhabited by a single insect that would give anyone a nasty sting. Placed in the foreground, it appears as gigantic as those bugs that roamed the Earth during the Carboniferous era, a mere 300 million years ago.

Peter Booth, Painting, 2022.Credit:Andrew Curtis, courtesy of the artist andMilani Gallery, Brisbane

This veering back and forth in time and place, catching snippets of half-remembered, half-imagined scenarios, echoes the world of dreams. Yet there is always enough reality – what Freud called the manifest content – to give weight and substance to Booth’s more bizarre and enigmatic images – the latent content. We feel these paintings and drawings are meaningful in the deepest sense, in a way the artist himself can’t explain. One suspects he would prefer not to attempt any explanations, which might undermine the weird power of these pictures or unearth buried traumas.

Psychoanalysis is known as “the talking cure”, but the greatest art exhausts and defeats the possibilities of spoken language. An image may address us on a deeper level than anything we can verbalise, touching on primal feelings that lie buried beneath the reach of consciousness.

Peter Booth’s Painting 1982.Credit:

There is a long history of such art, but not in Australia, where the bright light of day seems to dissipate those elements we call “visionary” or “gothic”. It’s seen as significant that Booth hails from Sheffield, an industrial town in the north of England bombed by the Germans in World War II. Born in 1940, Booth was too young to remember the bombings, but he grew up in a community that could never forget. He came to Australia in his late teens, a time of life when one’s personality is already inscribed on the psyche.

It may be impossible for the artist to escape his origins, but equally impossible for us to gauge the degree to which his later career was affected. What’s certain is that Booth stands at the end of a long line of artists who have explored themes such as the supernatural, the fantastic, the paranormal, and disturbed states of mind. One thinks of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel, of William Blake and Francisco Goya, Henry Fuseli, Edvard Munch, James Ensor and Alfred Kubin. His landscapes are often compared with those of Samuel Palmer.

Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare.Credit:Getty

The TarraWarra show includes a carefully chosen group of prints by Blake, Goya, Ensor and Palmer that reveal the family resemblances between their imagery and the later artist’s dark imaginings.

If there is one image of the past that leaps to mind when I think of Booth, it’s Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781), a work that exists in multiple versions. Fuseli’s depiction of a demon – an incubus – perched on a sleeping woman’s torso, while a ghostly horse’s head looms in the darkness, was a sensation when it first appeared. An icon of the early Romantic period, it has been copied and parodied up to the present day. The unique aspect of this picture was that it was entirely an invention of the artist’s imagination, with no reference to history, the classics or the Bible. As such, it issued an implicit challenge to the pre-eminence of History Painting, which Sir Joshua Reynolds had declared the highest form of art.

The Nightmare was an eruption from the subconscious that Fuseli was said to have accessed by eating raw pork before he went to bed. The painting would exert an influence on Mary Shelley when she sat down to write Frankenstein (1818) and have a similar impact on Edgar Allan Poe. In art, it opened the floodgates to a tidal wave of nightmare images that no longer required a sanction from the Academy or the classics. The British historian of popular culture Christopher Frayling allots the work a key role in the vogue for horror that would find expression in the “Gothic” novels of Ann Radcliffe, and continues to attract audiences to the cinemas today.

Peter Booth, Painting, 1981.

The eccentric Fuseli, who was Swiss by birth but spent much of his career in London, wrote: “One of the most unexplored regions of art are (sic) dreams”. In the 20th century the Surrealists would make dreams their special study, but there’s a world of difference between the quirky puzzle paintings produced by artists such as René Magritte and Max Ernst, and the anxiety and terror one associates with the nightmare.

In writing of nightmares in 1931, Freud’s disciple Ernest Jones observed how “no malady that causes mortal distress to the sufferer” was viewed with such indifference by medical science. This may still hold true because nightmares remain a mystery to psychoanalysts and scientists. We read about them eagerly in horror stories but have no desire to experience them ourselves. Indeed, our curiosity may be defeated by those shadowy corners of our minds the nightmare reveals.

Peter Booth’s Painting 2021.Credit:Andrew Curtis, courtesy of the artist andMilani Gallery, Brisbane

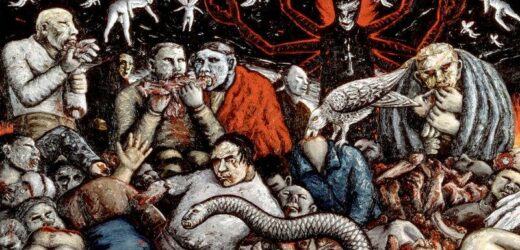

Most popular “horror” images are little more than self-conscious clichés, drawing on a conventional iconography of ghouls, ghosts, devils and demons. What makes Booth’s nightmare paintings so powerful is that he barely seems to be in control of the subjects that appear in his paintings and drawings. A truly horrifying work such as Painting 1982 (1982), with its vision of hideous, grey-skinned men feasting on human flesh, watched over by a many-armed insect man, goes beyond every zombie image dreamed up by popular culture. It’s a picture without explanation or context, dredged from the recesses of the artist’s mind and dumped on canvas.

There are details, even in this work, that set Booth apart: the carnivorous bird, the snake with a human face, and the little humanoid fairies that flitter around the top of the picture. Such things are not to be found in the zombie films that have become a familiar part of our popular culture – a phenomenon in itself that requires a lengthy discussion.

Peter Booth’s Painting 2018.Credit:

The sense of menace is less overt but just as keen in a work such as Painting 1998 (1998), which features a group of thuggish men led by a bald character with red eyes, who points to his right. He is clearly issuing a command, and we are expected to obey. If not, this leader has the muscle to enforce his orders. This image translates into a sense that we are being forced to do something against our inclinations, with a threat of consequences. It’s a common enough experience in dreams, in which all our daily anxieties take on a theatrical dimension.

Other works are pure emotional upheavals – flames, volcanoes, waterfalls, desolate landscapes that appear to have been blasted by war or natural disaster. These are all motifs with symbolic resonance, but their latent content is different for every dreamer. Booth’s volcano may have a different origin and meaning to any volcano we see in our own nightmares, but his image strikes a chord of recognition. More often than not, we feel an attraction to such images. There is something hypnotically beautiful in Volcano 1 (1993), with its yellow-and-red flames and lava, laid on in thick swathes with a palette knife.

The same applies to wintry landscapes such as Mount Donna Buang (1991), where the very absence of human beings induces a kind of frisson. Where have they gone? Or those tropical paintings in which nature is lush and overwhelming. There’s a beauty in these paintings, but also the feeling that the natural world has dispensed with our unwelcome services. Each forest or wasteland contains an existential threat, the unsettling feeling of being alone in a hostile environment.

Peter Booth’s Untitled 1995.Credit:

Amid all the breathtaking images assembled at TarraWarra, there’s one that niggles, by virtue of its relative calmness as much as anything else. Painting 1989 (1989) depicts a bald-headed man in an overcoat and a red muffler, standing in the snow. The longer I looked at this unassuming figure, the more closely it resembled Vladimir Putin, who has done more than anyone on the planet over the past year to dissolve the line between nightmares and reality.

Peter Booth is at the TarraWarra Museum of Art, Healesville, until March 13.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article