Why can’t people understand my grief for the children I never had: After two failed rounds of IVF, SAMANTHA BRICK’s final chance at having a baby was snatched away. Eight years on, her feelings are often met with a wounding indifference from society

A village welcome in rural France is always a warm, albeit nosy, one.

In 2014, soon after I moved into a farmhouse hidden away on the outskirts of a hamlet with my French husband, welcome drinks were held in the village hall and hosted by our mayor.

The idea was for us, and another newbie couple, to get to know our neighbours — all spread out in farms and smallholdings over many, many miles.

Pascal and I shared many similarities with that other couple — he was in his mid-50s and she in her early 40s — except for one small but crucial difference.

They had a baby with them and we did not. As the villagers cooed and passed the wee poppet around, I stood awkwardly on the sidelines and braced myself to bat away the inevitable question: ‘How many children do you have?’

To those who ask, it’s an innocuous getting-to-know-you question. Harmless chit-chat. But, for me, each time it was like a little stab to the heart.

Because no, I didn’t have any children and, at the time, I was coming to terms with the fact that I was likely never going to be a mum. Even today, eight years after recognising that motherhood was never, ever going to happen for me, it remains a viscerally raw feeling.

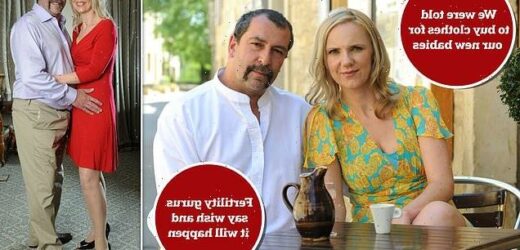

SAMANTHA BRICK (pictured with husband Pascal Brick): Even today, eight years after recognising that motherhood was never, ever going to happen for me, it remains a viscerally raw feeling

On good days I can put my best foot forward, focus on what I do have and breezily cope with such questions. And on bad days? I’m pretty much destroyed.

Autumn is a particularly tricky time. World Childless Week happens to fall in the middle of September and thanks to social media algorithms, no doubt because I’ve engaged or ‘liked’ such posts on this subject in the past, I always come across women sharing their deeply personal and utterly heart-breaking journeys of not getting to hold their own child in their arms.

I can lose hours online reading the stories of other childless women. In fact, I feel it’s my duty, because in witnessing their loss I’m legitimising it. Their grief is palpable, encompassing loneliness, shame, alienation and the all-consuming pain of not having a child — all feelings I recognise.

But it’s a unique type of grief and, even in 2022, society isn’t set up to support this kind of bereavement.

As I have discovered, people are well-practised at knowing how to support a parent who loses a child who lived, but there’s little thought given to those grieving the children they will never have — children who, to them, are just as real. When IVF has failed, it’s as if we’re expected to just go quietly.

This kind of loss is something that many parents find hard to understand. It’s why the words of writer (and new mother) Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett particularly resonated with me when she wrote recently: ‘Having a baby is hard, but the grief of not being able to have one can be even harder.’

This kind of empathy is so rare I wanted to applaud her generosity in acknowledging that women like me exist.

Given how little recognition we get outside the support groups, you might think we’re a small number, but we’re not.

Almost one in five women in their 40s and 50s are childless and academics estimate that 80 per cent of us will have been rendered childless by circumstance, as opposed to choosing actively not to become a mother.

I very much actively wanted to be a mother. I met Pascal, a carpenter, in 2007 on holiday, our romance playing out against the balmy backdrop of spring and summer in south-west France. We were married a year later and, as I was 37 and he was a decade older when we tied the knot, we decided we should try sooner rather than later to have a child of our own.

But it’s a unique type of grief and, even in 2022, society isn’t set up to support this kind of bereavement

It took us a year of wedded bliss before we got going but as Pascal already had three children, I believed him when he jokingly told me I’d fall pregnant in the blink of an eye. Yet I didn’t.

After a year of trying we were referred to a fertility clinic — tests concluded unexplained infertility — but another year passed while Pascal focused on custody issues with his youngest son, 12 at the time. I was 40 by the time joint custody was in place and we were accepted for IVF.

Like the 1.3 million women who have undergone IVF in the UK over the past 30 years, I embarked upon our journey optimistic that it would happen.

I was positive, taking fertility enhancing vitamins, staying fit and reading dozens (and dozens) of fertility and pregnancy books.

In short, I was doing everything I could to ensure my body was physically ready. As for the psychological preparations, there is a dazzlingly seductive fertility coaching industry primed to attract women like me — all aimed at persuading us that if we wish hard enough then it will happen.

The key to this is that we are supposed to visualise our perfect babies, talk to them, buy clothes for them and picture them in our arms.

We give them names, we know how we will decorate their nurseries, too. No wonder I felt bonded to my future child.

Don’t mistake me — I’m not blaming anyone. The likes of fertility gurus including Zita West Meads, Emma Cannon and Marisa Peer who all advocate this have helped thousands of women to get pregnant. It works — until it doesn’t.

I won’t moan about the hormonal highs and lows involved in fertility treatment, I was just grateful to get a go at it.

Even though our first IVF round in 2012 produced two excellent- graded embryos, they failed to implant. For our second attempt we avoided the state system in France, not least because their set- ups are unbelievably crass, with fertility clinics thoughtlessly situated next to maternity units.

That second attempt a year later at an all-singing, all-dancing clinic in Spain also didn’t work. But undeterred we were ready to give it a final go.

This time we would use a donor egg and I truthfully didn’t mind this option. We talked about the eye colour, height and background of potential donors. When you go over such biographical detail your baby becomes very real indeed.

We made appointments at the same Barcelona clinic for the autumn of 2014. Third time lucky I hoped. Yet earlier that year my eldest stepson had been diagnosed with stage three melanoma.

We were told it was terminal not long after I’d booked in for our third attempt. I quietly cancelled the appointment and never got to rebook it because my stepson died, aged just 27, in November 2014.

It was a completely devastating time. Understandably, Pascal was utterly consumed by grief.

Almost one in five women in their 40s and 50s are childless and academics estimate that 80 per cent of us will have been rendered childless by circumstance, as opposed to choosing actively not to become a mother (file image)

My husband’s pain at the loss of his son was accepted and understood by everyone in our social circle, in his family, as well as my own. He didn’t work for months, his hair went temporarily white and he struggled to get out of bed each day.

While I quietly held up the structure of our daily life, I simply wasn’t brave enough to remind him about our plans for us to become parents.

Instead, I silently carried my sinking agony in my heart. I didn’t dare discuss my feelings with anyone and, actually, no one asked me either. I know people didn’t mean to be callous but they just didn’t think to enquire.

Because my grief at watching the door close on my dreams of creating a child with my husband isn’t considered real or appropriate in our society.

It’s only recently I have discovered that my feelings are known as ‘disenfranchised grief’, when family members, social groups, and society don’t recognise a loss.

To put it bluntly, grieving for a child who never lived isn’t, in the eyes of our world, a legitimate form of grief. Yet I’d argue it is healthy and right to grieve over our lost dreams. Of not getting to hold our own baby, applaud their first steps and listen to their first words.

Remember, women like me have spent years, sometimes decades, trying to create this.

Had I known about this form of grief, perhaps I’d have been easier on myself.

At first, I didn’t understand why some evenings during the following spring, I took to bed earlier than usual, closing the door on other people, just listening to the birdsong outside the window while silently crying into my pillow. I did see our GP who instantly prescribed antidepressants. While the numbness helped, I stopped them a few months later because they did nothing to alter the root of my pain — that I wouldn’t become a mother.

Did I ever discuss this with my husband? No, how could I when he spent evenings looking at family photo albums of his son as a baby, toddler and teenager?

At the time, I believed my feelings were inferior to his. I now know and truly believe — as hard as it is for parents who have lost living children to hear this — that my grief is as justified.

Society publicly props mothers and fathers up when they lose a son or daughter but women (and men) who don’t get their warm bundle at the end of their fertility journey?

Well, we’re just expected to buck up and bloody well get on with life.

The fertility industry really isn’t geared up to support women like me, either. They only want to sell the success stories and push the miracle baby industry.

There is very little information (much less help) to be found about the reality when it fails.

Click on the glossy websites for those expensive fertility clinics, sit in the waiting rooms and you are surrounded by images of perfect babies and happy, complete families.

Women are hardwired from the moment we enter this world to believe it is going to work. Little wonder we crash when it doesn’t.

Even though my family and best friend have been unwaveringly supportive, the reception we get from others, especially other women, can be callous.

Like the 1.3 million women who have undergone IVF in the UK over the past 30 years, I embarked upon our journey optimistic that it would happen (file image)

I tell myself they don’t mean to be so staggeringly rude and utterly insensitive (tasteless comments on social media made by mothers such as: ‘What planet is she on! She’s lost the plot if she thinks grieving for a baby you didn’t have is the same as losing an actual child’.)

It’s also common for people to say ‘you don’t miss what you’ve never had’.

Being childless is a triple whammy of yearning for what we’ve never had, yet feeling like we should be grateful for what we do have and feeling bad if we still want what others have.

And there are a million reasons why adoption and fostering aren’t an option for everyone either.

I lived with the ghost of my daughter — I’d always assumed I’d have a girl at least — for many years.

But is it any wonder she felt so real? After all there were still booties I’d bought, tucked into the bottom drawer of my office cabinet.

Who am I kidding? That drawer was filled with paraphernalia I’d dared to buy. Babygros, teething toys, first word books — all part of manifesting the life I would have with my baby. Part of the grieving process for me was to let go. And only during lockdown did I finally do so. I calmly took one last flick through all those books and put them all on eBay.

The toys and clothes I took to the local charity shop.

Now, I’d describe the grief as a bruise that sits inside me. Most of the time it doesn’t hurt, but press it and the pain is sharply intense.

Writing this has inevitably pressed the bruise and has been a stop-start process because I have again sobbed buckets for a life that I never got to live.

If those first two embryos had taken, then their due date would have been December 2012. Today they’d be almost ten and celebrating their birthday during the month when both my nieces and both my nephews were born.

But while writing this is deeply personal, it is a part of who I am and I don’t want to hide it or feel ashamed any more.

I also want to share my feelings because I know I’m speaking for many women like me and if it helps society to acknowledge the grief for women who don’t get to be mothers, then it is a welcome start.

We’re here, we live among you and while we’re happy for your families, our melancholy and pain is real.

So the next time you see or learn of a woman like me, please be gentle with us. Consider the impact when you enquire: ‘Do you have any children?’

Our grief exists, it is legitimate and it never goes away.

Source: Read Full Article