Ahmir Thompson, better known as Questlove, is the director behind the documentary “Summer of Soul,” which captures an important part of Black history, culture and music.

In 1969, the Harlem Cultural Festival took place, a series of concerts that came to be collectively referred to as a Black Woodstock, except unlike Woodstock, it was nowhere to really be seen. The shows were unknown even to most music cognoscenti until Thompson discovered there were over 40 hours of footage in existence, captured by producer Hal Tulchin.

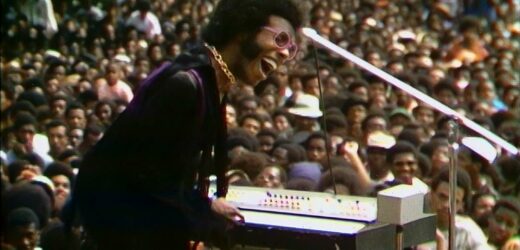

From footage of Stevie Wonder at a turning point in his career to Mavis Staples duetting with Mahalia Jackson to the golden era of Sly and the Family Stone, the documentary extraordinarily tracks a cultural event while showing the socio-political climate of the time.

Below, Thompson and editor Joshua Pearson discuss how the film came together.

Where did the idea of telling this even begin for you?

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson: The seed was planted 20 years ago. The Roots happened to be in Tokyo, Japan in 1997 and my translator took me to a restaurant called the Soul Train Cafe. They would have these monitor installations all over the wall playing archival footage. James Brown was on one screen, and there was one with Sly and the Family Stone (from the Harlem Cultural Festival), and I was watching five to six minutes of this footage.

Cut to 20 years later: These two gentlemen approached me about having 40 hours of footage of this amazing concert that went down in Harlem, akin to Woodstock, which at the time everyone called the “Black Woodstock.” I was easily cynical because my ego wouldn’t allow me to believe that there was something that monumental has happened in music that I didn’t know about. Furthermore, if it’s not on Google, it never happened. That is the sad thing about erasure; before our movie, you barely got anything about it. It was just rumored that maybe this happened.

When they dropped 40 hours of footage in your hands, that’s something to behold and take in because now you’re dealing with history and people’s histories… as much as I didn’t believe or had doubts that this even happened. You have a whole slew of people that went there that nobody believed them, and it’s like the little boy that cried wolf. All these worlds are meeting at the same time. It suddenly went from “I don’t believe this happened” to “Oh shit, this really did happen” to “Oh, God, this is history.” This is a vital piece of missing history.

That footage is over 50 years old. Joshua, talk about weaving together this narrative.

Thompson: I have to say, the original tapes were in Hal Tulchin’s basement for five decades. These tapes were in these blue-like Tiffany boxes. There were concerns because they were done on the first uses of video. When I first saw them, I was hoping there were in 16mm or 35mm, but they were done on the first uses of video. They looked like a news report, and there are only seven people in the United States who know how to deal with this technology. We tracked two gentlemen in Long Island and they had to purchase 12 broken-down machines, just to build the perfect one, just so that they could bake the film, treat it and send it to Josh. Josh, to me, is one of the most perfect editors. He’s a musician and there’s a rhythm there already.

Joshua Pearson: By the time I came on the project, Amir had already absorbed all this footage, and I honestly did not have to watch all 40 hours because Amir has already watched it on a loop over and over again. He had already created a pretty strong playlist of what we were going to try to tackle in this film. We worked closely with Amir’s producer, Joseph Patel, and it was this three-person brainchild. We sketched out what the arc of the story would be in this film, which is this transformation of Black music from the more traditional to the futuristic, and also, what was happening socio-politically in 1969 for Black culture, which was going from the nonviolent resistance of Martin Luther King to the more militant approach of the Black Panthers and other militant groups.

Meanwhile, I knew that this was a great opportunity for me to revisit a style of editing that I’ve not really been able to use since the 1990s when I was making a lot of music. I was in a group called Emergency Broadcast Network, and we were heavily influenced by Public Enemy. This film became an opportunity to edit in a more syncopated DJ style.

As you say, you set the socio-political time, but then you have the interviews with Lin-Manuel Miranda, in addition to the footage. How did you structure that into the roadmap of it all?

Thompson: So this is weird. As a member of the Roots, and living in a tour bus for 200 days of the year, it was my job to provide the entertainment and distraction so that the 16-hour trek from Chicago to Denver wasn’t as bad. I probably purchased maybe over 4000 DVDs. The whole point is that there are only so many ways that you could watch “Goodfellas” or any movie of your choice before it just starts getting to “I’ve seen this 10 times already and I discovered the director’s commentary.” And up until recently, Stevie Wonder put me on to audio descriptions, which is like having your own personal Morgan Freeman to give you the narrative. It helps a lot if you’re trying to learn how to be a screenwriter, and this is how I’ve been watching films for the last 10 years.

It’s weird to me when people started making a big deal of how this film packs in so much information, and it’s dizzying but it’s comprehensive at the same time. But that’s how I take in so much of my movies. I’m trying to educate people, as long as I’m allowed to. I feel like it’s a waste if you’re not giving context to something. In making this, I became more aware, more hyper-aware, that people won’t understand history unless there’s context to it, so I added that in.

Source: Read Full Article