“I don’t see fashion as curing cancer or AIDS – or anything else for that matter,” said Alexander McQueen. “At the end of the day they are just clothes.” This statement, like so many others uttered by this prodigiously talented designer, testifies to the contradictions that defined his career and character. For McQueen (1969-2010), fashion was everything or nothing, depending on how he felt that day. In less than two decades he stood the industry on its head, before committing suicide at the age of 40 when his fame and influence were at their height.

Alexander McQueen: Mind Mythos Muse at the National Gallery of Victoria is set to be the blockbuster of the summer. Drawn exclusively from the collections of the NGV and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, it’s a breathtaking exhibition that explores the full range of a uniquely fertile imagination.

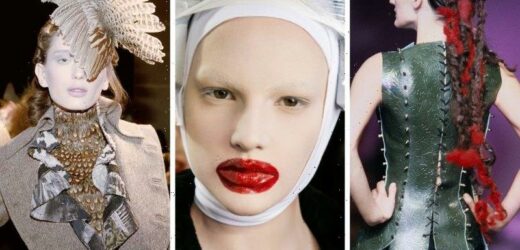

Alexander McQueen, from left: Highland Rape collection, AW 1995–96; backstage at the launch of the Horn of Plenty collection; The Widows of Culloden collection, AW 2006–7.Credit:Robert Fairer © Alexander McQueen

There are still some museums that refuse to consider fashion as a worthy subject for a show. It was once argued that fashion was a commercial affair, whereas art somehow transcended the grubby marketplace. To believe that today is to believe in fairies at the bottom of the garden. The best fashion is great art, the most banal art is pure commerce.

McQueen’s reputation was set in gold when the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York hosted the 2011 survey Savage Beauty. In only three months it became the second-best-attended exhibition in the Met’s history. When a version was restaged at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum in 2015, it attracted more than 480,000 visitors, making it the museum’s most popular show of all time. Small wonder the NGV is buzzing in anticipation of some big numbers.

To understand McQueen’s phenomenal appeal, one has to look at the nature of his work, the fashion industry, and the man himself. Born into a working-class family in south-east London in 1969, as the youngest of six children, Lee Alexander McQueen was reputedly making fashion decisions by the age of three, telling his siblings which clothes went together. At school, he was a misfit, being nicknamed “Queer Boy, Queeny”. He was artistic but also tough and would cheerfully describe himself as an East End yob.

McQueen left school at 16 and worked as an apprentice for two firms in Saville Row, picking up skills many designers never acquire. He proved to be a virtuoso with a pair of dressmaker’s scissors, able to cut the fabric for pants and jackets by eye alone. He would spend the best part of a year in Milan, working for Romeo Gigli, having secured a job by just walking in off the street. This experience would provide him with an insider’s knowledge of the industry by the age of 20.

Designer Michael Schmidt with some of his head pieces at the opening of the Alexander McQueen exhibition at the NGV. Credit:Wayne Taylor

When McQueen applied for a job at Central St. Martins School of Art, he was encouraged to enroll in the MA program on the strength of his experience and portfolio. Already, he had a taste for the dark side and a willingness to push himself to extremes. He spent his evenings in gay bars, immersing himself in drink, drugs and random sex. His attitude to work was no less manic and exhausting. Friends consistently remember how intelligent and funny he was, but also prone to bouts of insecurity, depression and anger. It was a pattern that would continue throughout his life, a textbook example of a bipolar personality.

From his earliest days, McQueen set out to distinguish himself from the pack. Although there is nothing unique in a designer borrowing from diverse sources, or staging shows that aim to shock or offend audiences, no other couturier has done this so wholeheartedly. McQueen’s graduate exhibition from Central St. Martins in 1992, was titled Jack the Ripper Stalks His Victims. It featured 10 outfits incorporating human hair and slash marks.

The show attracted the attention of socialite and pathological fashion victim, Isabella Blow, who purchased the collection and began a life-long fixation with McQueen, becoming his muse and mentor. The Powerhouse hosted a show of Blow’s collection in 2016 which didn’t get the attendances it deserved. Foul-mouthed, extroverted, and probably psychotic, Blow would commit suicide by drinking weed killer in 2007. She played a big part in McQueen’s success story, relentlessly promoting his work until he became so famous she was a liability.

Much of the early work, and some rare, expensive items are missing from the NGV show, but I can’t see anyone being disappointed by this display, which captures McQueen’s extremity and his love of beauty – albeit of an unconventional kind. His credo was that beauty can come from “even the most disgusting places.”

Director Tony Elwood at the opening of the NGV exhibition. Credit:Wayne Taylor

The pressure of being chief designer for a big fashion house is stupendous, and McQueen worked with both Givenchy and Gucci while maintaining his label. At its peak, this meant he was designing four collections a year, each one scrutinised by press and clients, ready to criticise every perceived weakness. To fuel this constant demand for creativity, designers grasp at any source of inspiration, particularly the fine arts. Yves Saint-Laurent produced an entire line of dresses based on Mondrian paintings for instance, but McQueen was more brazen in his borrowings. Garments emblazoned with Don McCullin’s war photographs resulted in a lawsuit from the photographer. Joel-Peter Witkin, known for his images of death and deformity was a particular favourite.

In this exhibition, the curators have paired McQueen’s costumes with sources of inspiration, or very similar works. A small painting by Jan Mandijn (1500-60) of Saint Christopher and the Christ child represents the work of fantastic Flemish artists such as Hieronymus Bosch, that inspired McQueen’s final collection, Angels and Demons (2010-11).

Elsewhere, prints of the bullfight by Goya and Picasso relate to the collection The Dance of the Twisted Bull (2002), while extracts from Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon (1975) are being shown alongside clothes from Sarabande (2007). Deliverance (2004), based on Sydney Pollock’s 1969 film They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? is exhibited with American photographs of the Depression era by figures such as Dorothea Lange. Perhaps the most dramatic section features a large selection from the 2006 collection The Widows of Culloden – all tartan, tweed and bagpipes (as headdress!) – set against grey, stormy weather, and a huge portrait of the Earl of Eglinton by John Singleton Copley.

Conservator Viki Car with two pieces from Alexander McQueen’s Horn of Plenty that feature in the NGV exhibition.Credit:Scott McNaughton

These theatrical settings provide insight into McQueen’s way of thinking, but they don’t account for his unconventional choice of subjects. It’s hard to imagine another designer creating a collection based on the Salem witch trials, or calling another, Highland Rape. McQueen was an admirer of Leigh Bowery’s extreme performances, and the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom – that progressive list of perversities composed while Sade was imprisoned in the Bastille in 1785. The “Divine Marquis” was a forerunner of the avant-garde artist who aims to continually stretch the boundaries of what is possible.

McQueen took the same approach in striving to disconcert his hard-bitten audience. It was partly the class hatred of an “East End yob” who found himself feted by the rich and famous. It was also bound up with his feelings about an industry that could be so utterly fatuous. Some argue that McQueen’s real talent was as a maker of theatrical spectacles, but one should not underestimate the quality of the garments he created, many of them surprisingly wearable.

McQueen wanted his work to be meaningful, to expose the dark side of the human condition, to rage against historical injustices such as the Highland clearances. He absorbed information in an unsystematic manner from books, movies, TV, what he saw on the street or experienced in his own life. He also knew that haute couture thrived on publicity, and that his appeal to firms such as Givenchy and Gucci came from his shock value, both as a stimulant for the jaded palettes of wealthy clients, and as fodder for the tabloids. The more notoriety McQueen brought to a label, the more perfumes, handbags and accessories they would sell. That’s where the real money in the fashion industry lies, not with the elite circle gathered around the catwalk.

This ambiguous role, rather like being the jester at Bernard Arnault’s court, pushed McQueen to ever greater extremes, fuelling his own manias and insecurities. His friends would describe his multiple personalities: shy and sensitive one day, and a raging despot the next; desperate for love but treating his companions with abject cruelty.

Curator Danielle Whitfield with one of the 110 garments in the show.Credit:Eugene Hyland

Looking at this exhibition, one realises how pathetic it is to tag McQueen with titles such as the enfant terrible or “bad boy” of British fashion. Although he shared the provocative attitudes of a generation that gave us artists such Damien Hirst or Tracey Emin, he was more talented than any of them. Most of the bad boys and girls one encounters in the worlds of art, music and popular culture are hardly more than carnival acts – a series of shallow poses calculated to attract attention.

McQueen was no phoney. He pushed the boundaries because he had no choice, being driven by his personal demons. At the same time, he was a perfectionist who took infinite pains with the construction of a garment. Today, more than a decade after his death, he seems edgier than ever. The accusations of misogyny, cultural insensitivity, exploitativeness and sadism that were continually raised in reviews of his collections, have lodged themselves in the minds of his admirers as well.

In the catalogue of this exhibition, writers make excuses for McQueen’s use of Arabic motifs in his Eye collection of 2000, worried that the world of culture has become an infinitely more delicate place recently.

McQueen always argued that rather than being anti-woman, he wanted to dress women in such a way that they became strong and even dangerous. If he borrowed motifs from Islamic culture, or other taboo sources, it was a way of investing power and glamour in things considered “other” to western culture. As a lifelong misfit, he was acutely conscious of things excluded by the mainstream. As a working-class gay man who struggled with his own body image, he sought to break down the fashion industry’s taste for idealised forms that left most of humanity out in the cold. That he did this in the most explosive, aggressive, operatic manner is what set him apart from the rest. In these politically correct times, it may not be long before McQueen’s brand of outrageous fantasy is considered to have no place in the temples of high culture. Best get in quick and see it while you can.

Alexander McQueen: Mind Mythos Muse is at the National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, until April 16.

To read more from Spectrum, visit our page here.

A cultural guide to going out and loving your city. Sign up to our Culture Fix newsletter here.

Most Viewed in Culture

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article