By John McDonald

An illustration from 1493’s Liber Chronicarum by Hartmann Schedel.Credit:Getty

Every era responds to a crisis in its own way. Our answer to COVID-19 has been to bunker down, trust in science, and wait out the worst of it. In the late Middle Ages, when Europe was devastated by the Black Death, it was widely believed the illness was sent by God as punishment for human wickedness and depravity. The physical effects of the Plague may have been horrifying, but it was also a sickness of the soul.

In an age of faith, sermons would portray life as little more than a preparation for death. There may have been a genuine belief that attaining the Kingdom of Heaven was more important than the brief span of our lives on earth, but it was also a way of reconciling the poor to their destiny. If you were born a peasant under feudalism, you could look forward to a lifetime’s labour for the lord of the manor with little chance of escape or advancement.

The average life span from 1200-1300 was 43 years, but it fell to 24 years from 1300-1400 because of the Plague, which killed up to a third of the population in some regions. Other factors were the high rate of infant mortality and the primitive state of medicine.

Death was ever-present in a way that can hardly be conceived of today. Rather than brooding on their fate, people embraced it in ways that provided a release from tension and anxiety. One outlet was the Dance of Death – la Danse Macabre, der Totentanz – in which, at carnival time, people would dance around with characters dressed as skeletons.

The Dance of Death was one of the few truly egalitarian things in a rigidly hierarchical age. Death did not discriminate between kings and commoners, priests and peasants. Typical artistic representations of the Dance of Death, found in wall paintings and book illustrations, featured the Pope, the Emperor, assorted cardinals and nobles, labourers, beggars, and usually a small child. The victims look glum, or at least blankly resigned to their fate, while the skeletons are joyful and animated, eager for a jig.

The Dance of Death was one of the few egalitarian things in an hierarchical age. Death did not discriminate between kings and commoners.

The pictures were often accompanied by captions that made the messages even more unmistakable. In an old Heidelberg manuscript from the 1440s, Death tells a cripple: “A poor beggar here in life/ No one at all is a friend/ but Death will be his friend/ He takes the poor away along with the rich.” By contrast, the Emperor is told: “Mr Emperor, the sword doesn’t help you/ Sceptre and crown has no value here.” A small child complains: “Now I must dance and can’t even walk.”

The earliest recorded artistic treatment of the motif was a mural at the Holy Innocents’ Cemetery in Paris, painted in 1424-25. This work was destroyed long ago, as was a monumental painting from the end of the 15th century by Baltic artist Bernt Notke (c.1440-1509). The piece, 30 metres in length, was originally installed in a church at Lübeck but 300 years later it was in such bad condition that a full-scale copy was made. In 1942, the church and the copy would be destroyed by Allied bombs. It exists today only as a black-and-white photo.

People are surprised in the midst of daily activities: The Dance of Death: The Mendicant Friar; The Nun by Hans Holbein.Credit:Getty

A fragment of another early copy remains in the Church of St Nicholas, in Tallinn, Estonia. This painting was evacuated in time to avoid destruction by Soviet bombs in 1944. An equally famous mural in Basel, dating from 1435-1441, was torn down by local citizens as late as 1805, on the grounds it was a “scandal” and a hindrance to traffic.

The most famous versions of the Dance of Death were created by Hans Holbein the Younger (1497-1543), whom we know as one of the greatest portraitists of all time through his work at the Court of Henry VIII. Holbein designed this series of 41 woodcuts in 1526, while still residing in Basel. The images were published in 1538 and became instant best-sellers due to their exceptional quality and Holbein’s inventive, satirical approach. Instead of Death’s victims standing immobile between cavorting skeletons, people are surprised in the midst of daily activities.

Hans Holbein’s series of woodcuts were instant best-sellers due to their exceptional quality and the artist’s inventive, satirical approach: The Child, circa 1526.Credit:Getty

The Duke is grabbed by Death as he is turning away the entreaties of a poor woman and child. A heavily laden merchant is stopped by a skeleton who offers to lighten his load. A nun is kneeling in prayer alongside a lover when Death arrives to snuff out her candles. The Pope is grabbed as he is about to place a crown on the head of the Emperor who is kissing his feet. The judge is interrupted while taking a bribe. The miser is powerless to stop Death from stealing his money. Cruelty, greed, hypocrisy and other vices are punished, while suffering is alleviated.

Holbein’s anti-clerical images were broadly supportive of the Reformation but have universal relevance. By turning Death’s “dance” into a series of discreet vignettes and dressing the Grim Reaper in a startling variety of costumes, he took a medieval motif and refreshed it for an early modern audience.

From Thomas Rowlandson’s The English Dance of Death, 1815Credit:Getty

The satire was perpetuated by Thomas Rowlandson (1742-1843), in his series The English Dance of Death (1815-16). Rowlandson’s characters are grotesque caricatures for whom Death shows scant respect. Sports and pastimes prove fatal, as does a visit to the apothecary, who is selling cures concocted by a skeleton hiding behind a curtain. This sort of bawdy, irreverent satire flourished in Georgian England at a time when many European states were imposing the strictest censorship.

Grotesque caricatures for whom Death shows scant respect: The Sot from Thomas Rowlandson’s satirical series The English Dance of Death.Credit:Getty

The two sins most frequently reviled by the medieval Dance of Death were Pride and Avarice, but we’ve travelled a long way from a moralistic memento mori to a scattergun critique of corruption, decadence and superstition. The motif continued to evolve in musical form, with dramatic pieces by Liszt and Saint-Saens (and most recently the British composer Thomas Adès); and in literature, with poems by Goethe, Browning and Baudelaire; a play by Strindberg, and a strange, nihilistic theatre scenario by W.H. Auden. This in turn fed back into the visual arts.

One finds echoes of Baudelaire’s dark symbolism in The Dance of Death (c.1865) – an etching by his friend, Félicien Rops (1833-98). Here Death is no longer an equal-opportunity enforcer of destiny or a moral avenger, but an aged coquette in a fancy bonnet who lifts her skirts to reveal a withered set of buttocks. The skeleton looks back over its shoulder, attempting a seductive expression.

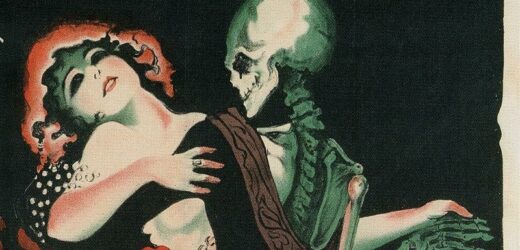

Poster of The Dance of Death from 1910s.Credit:Getty

This Dance of Death is a perverse can-can, almost a transcription of Baudelaire’s poem, which verges on necrophilia (“Who’s not squeezed a skeleton with passion”) but is more likely a bitter reflection on the venereal disease that made the poet’s life a misery. Syphilis and gonorrhea were rampant at the time, prompting grim associations between sex and death.

Rops’ contemporary, James Tissot (1836-1902), adopted a self-consciously romantic stance in a painting that harks back to medieval times. In The Dance of Death (1860) a group of richly dressed revellers on a hilltop prance and gambol, seemingly oblivious to a corpse lying on the ground in their midst. Two skeletons bring up the rear, one carrying a coffin.

A group of richly dressed revellers on a hilltop prance and gambol, seemingly oblivious to a corpse lying on the ground in their midst.

The figures silhouetted against the sky are reminiscent of the famous scene at the end of Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal (1957), which reputedly came together spontaneously during shooting. Could Bergman have seen Tissot’s painting?

For a much closer connection between painting and film one might look at Edvard Munch’s claustrophobic image, The Dance of Life (1899-1900) and Herk Harvey’s B-grade horror classic, Carnival of Souls (1962). Although Munch’s title stresses “life” instead of “death”, there’s nothing life-enhancing about this painting which seethes with jealousy and anxiety, as young and old versions of the same woman glare at a hollow-eyed dancing couple. In Harvey’s cult movie, Munch’s dance is re-staged with a room full of ghouls whirling around a deserted ballroom.

There’s nothing life-enhancing about this painting: Edvard Munch’s The Dance of Life’, 1899-1900. Credit:Getty

The dance has taken on a sinister, personalised tone in Munch’s painting. It is being played out in the artist’s mind, coloured by his own anger and paranoia. In Carnival of Souls, we spend most of the movie trying to work out what is real and what is merely a hallucination as the lead character slips ever further into her own nightmares.

All this is a long way from the carnival atmosphere that characterised the medieval Dance of Death. The true heir to this tradition may be the Mexican artist, José-Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913), whose pictures of partying skeletons, such as The Folk Dance Beyond the Grave (c.1910), are steeped in the Dionysian revelry of the annual Day of the Dead celebrations.

Mexican artist José-Guadalupe Posada’s images are steeped in the Dionysian revelry of traditional Day of the Dead celebrations.Credit:Getty

When I set out to research the Dance of Death I thought I’d find a few memorable works made in response to the pandemic, but while there are plenty of skeletons very few of them are dancing. It might have been expected that COVID-19, with all its morbid folly, would lend itself perfectly to such a motif. The lack of such images is symptomatic of the way we see ourselves. For us, the pandemic is not an excuse for wild abandon but seclusion. Parties and dances are strictly forbidden, and there’s nothing celebratory about mindless demonstrations by militant anti-vaxxers.

Despite the perpetual furore generated by religion, the virus reveals the thoroughly secular nature of the developed world. We are not throwing ourselves on God’s mercy and embracing fate but resisting the very notion of death. In the Middle Ages people lived with death and thought about it every day, but today we put it out of our minds, wishing it would go away. It’s almost axiomatic that as a society begins to believe in its own perfection it wants less and less to do with this intractable subject. When Death comes knocking on the door and invites us to dance, we pretend there’s nobody at home.

www.johnmcdonald.net.au

In need of some good news? The Greater Good newsletter delivers stories to your inbox to brighten your outlook. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Culture

Source: Read Full Article