From the day Javeria and Usman Ahmad brought their baby boy, Ismaeel, home from hospital, the family lived in self-imposed lockdown for two years, long before anybody had heard of Covid-19.

They had no visitors, washed their hands with military precision and disinfected all surfaces before sanitising stations flanked every storefront.

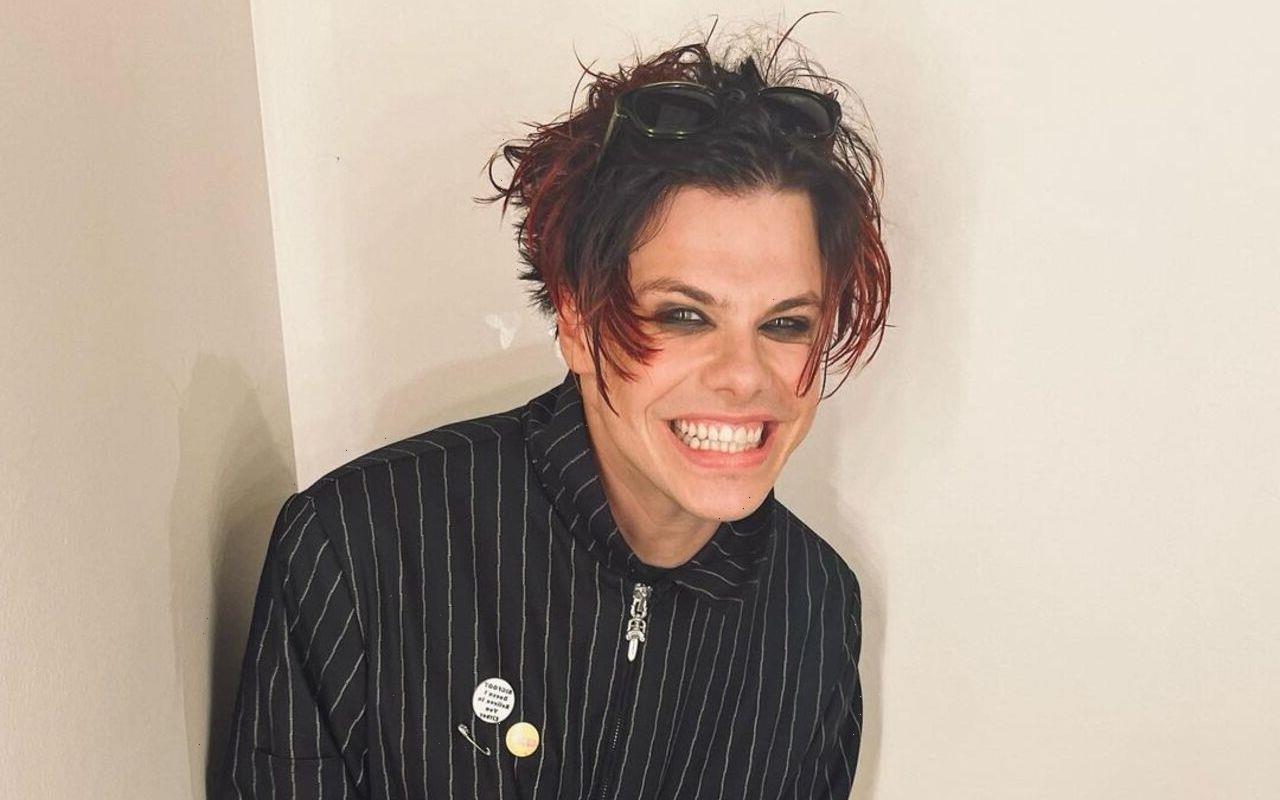

Ismaeel Ahmad (centre front) and his father Usman (left), mother Javeria (right) and sister Rumaysa (back) at their Merrylands home.Credit:Rhett Wyman

Ismaeel’s big sister, Rumaysa, was held back from kindergarten to avoid the risk of her bringing home any of the usual bugs children swapped in the playground.

“We were so cautious, so paranoid,” Javeria said. They knew the tragic consequences that a lapse in vigilance could precipitate.

Ismaeel has a rare genetic disorder, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), known as the “bubble boy disease”.

His brother, Zakariyah, died of the same condition in 2014, at just 15 months old.

Their little bodies cannot produce the infection-fighting cells that protect them from invading viruses and other diseases.

“Ismaeel sometimes asks me, ‘What am I allergic to’ and I’d say ‘germs’,” Javeria said.

He was diagnosed early, which gave him an excellent chance of survival with treatment. But he was still vulnerable, even after a bone marrow transplant from his father, which partially fortified his immune system.

You wouldn’t know it to look at Ismaeel today. He is thriving thanks to fortnightly infusions of a life-saving medicine of infection-fighting antibodies made from the blood plasma donated by strangers.

“He’s the class comedian,” Javeria says of the golf-obsessed seven-year-old who goes to school with his mates in Merrylands in Sydney’s west.

“Without the infusions, he couldn’t live a normal life. We’d be back in lockdown.”

Demand for blood plasma is at record levels, prompting an urgent call for 200 additional plasma donors every day in October to treat the tens of thousands of Australians whose lives depend on it.

Australian Red Cross Lifeblood’s stockpiles of blood plasma are primarily maintained by just 30,000 donors, despite more than 10 million people being eligible to donate.

Lifeblood’s chief executive Shelly Park said thousands more donors are needed to meet the growing demand driven by improvements in diagnoses.

Javeria Ahmad gives Ismaeel his fortnightly infusion of medication made from donated blood plasma.Credit:Rhett Wyman

Doctors are finding more uses for blood plasma across an expanding array of acute and chronic medical conditions including cancer, immune disorders, haemophilia, kidney disease and trauma patients, Park said.

Over the last two-and-a-half years of the pandemic, donors were urged to make whole blood donations to help meet the highest demand for red cells in nearly a decade, but that came at the cost of plasma donation.

Global demand for plasma rises by about 10 per cent each year, and Australia is of the top three users of plasma medications per capita in the world to treat more than 50 medical conditions.

“Plasma is a global precious health resource, containing dozens of antibodies and proteins that we are unable to replicate inside a lab. It truly is magical – a life-saving natural resource,” Park said.

Just one of these medicines, immunoglobulin (Ig), is essential for more than 13,300 Australians who need it every month to treat their acute or chronic conditions,” Chesneau said.

Every Australian who has had post-exposure tetanus or chicken pox injections, or pregnant women who have had Anti-D injections has benefited from plasma donations, Chesneau said.

But it can take up to 13 plasma donations to make a single dose of some plasma medicines.

Lifeblood and Immune Deficiencies Foundation Australia are launching International Plasma Awareness Week from October 3 to 7.

Immune Deficiencies Foundation Australia Chief Executive Carolyn Dews said thousands of

People with immune deficiencies rely on the generosity of plasma donors.

“Plasma provides them with protection as it contains disease-fighting antibodies that help to protect against a range of infections,” Dews said.

There are three kinds of blood donations: whole blood, plasma and platelets

Whole Blood donation

This is the fastest and simplest form of donating blood. Once blood is drawn from your arm it is usually separated into red blood cells, plasma and platelets in the lab.

It takes 10 minutes to donate 470ml (about 8 per cent of the average adult’s blood volume). You can donate whole blood every 12 weeks.

Plasma donation

The process of donating plasma is called ‘apheresis’. It involves a special machine that uses centrifugal force to separate the blood drawn from your arm into plasma (which is yellow in colour) and your red cells. You can see this happening in the apheresis machine while you are donating, and your red cells are returned to your body during the same appointment.

Donating plasma rather than whole blood means twice as much plasma is collected (over half your blood is plasma), and you can donate more frequently (every two weeks).

It takes between 45 minutes and 1.5 hours to donate.

Platelets donation

Platelets are tiny fragments of cells made in bone marrow. They only last seven days after donation. Platelets clump together to stop bleeding, seal wounds and help plug leaks in damaged blood vessels.

It takes an hour to donate, and about two hours for the whole appointment. You must be male and have donated plasma before to donate platelets.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article