STEPHEN GLOVER: Immigration is making the housing crisis worse. So why won’t any MP dare to admit it?

Many young people are understandably angry about the lack of affordable housing. They look with envy at parents and grandparents, who had an easier time setting up home.

I expect they will be outraged to learn of a rebellion on Tuesday night by some 50 Tory MPs, who voted to ban mandatory housing targets in England. It is thought the Government will now abandon them.

The Government’s ambition of setting a figure of 300,000 new homes a year was frustrated by ‘Nimbyist’ Tories who don’t want Whitehall imposing quotas in their constituencies, often in the Home Counties.

In fact, whether as many as 300,000 houses could be built in a year even with less strict planning laws is doubtful. Last year there were about 175,000 new homes. The last time the 300,000 annual target was met was in 1977.

Nevertheless, many will fume at the selfishness of the Tory rebels, and one can see their point. With current population trends, houses will remain expensive, and in short supply in parts of the country, unless by some miracle many more are built.

It’s easy to criticise the Nimbys, but the truth is that most of us are dismayed by the prospect of more building in our own back yards. At the same time, we go through the motions of feeling sorry for the younger generation who can’t get on the housing ladder.

No one seems ever to ask why we need so many new houses. The late journalist Auberon Waugh used to complain that it was the consequence of more couples getting divorced. If only they would stick together, he argued, we wouldn’t have to despoil our green and pleasant land by putting up new homes for single people.

Many young people are understandably angry about the lack of affordable housing. They look with envy at parents and grandparents, who had an easier time setting up home

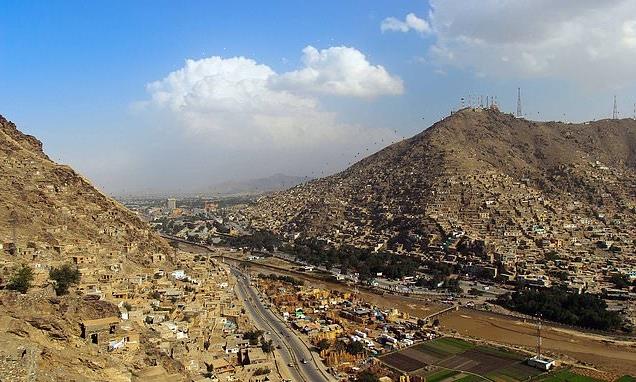

For all the Government’s talk of the need to control our borders after Brexit, the fact is that annual net migration hasn’t declined, and is probably now rising. I haven’t even mentioned the 40,000-odd so-called asylum seekers who have already crossed the Channel this year. Pictured: RNLI lifeboat escorting 80 migrants to Dover in June after they were picked up in the English Channel

There is another, much more powerful contributory factor that has been driving up house prices for 20 years and more, which almost no one mentions. It is the elephant in the room. I mean, of course, immigration.

Whenever politicians discuss the question of affordability of homes, or the matter is debated on the BBC, one can be practically certain that no one will dare raise the dreaded ‘I’ word.

Presumably they are terrified of being thought racist. No leading politician will dare address the issue in public. And yet it can’t be denied that mass immigration since the beginning of the century has greatly worsened the housing problem.

According to an official 2018 report by the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government, between 1991 and 2016, immigration drove up house prices in England by about 20 per cent in real terms.

The excellent think tank MigrationWatch estimated in 2019 that, if net migration continued at a then recent historical annual average of 214,500, about 89,000 homes a year would be needed.

In fact, annual net migration is significantly higher. In the year ending June 2021, it was estimated at 239,000. This morning, the Office for National Statistics is due to issue a figure for the year to June 2022.

It is widely expected to be higher than that for the previous year. Given that the Government has been handing out work visas in record numbers, it could be considerably higher.

This means that, notwithstanding Brexit, we may soon be approaching the record annual net migration figure reached shortly before the June 2016 referendum. We have already easily surpassed the totals for 2012 and 2013.

You wouldn’t think so if you listened to Tony Danker, head of the CBI, who said at the organisation’s conference in Birmingham earlier this week that more foreign workers should be brought in to ‘plug the gaps’ in the labour market. He, and others, have painted a picture of a dire shortage of workers.

Needless to say, none of them seems remotely concerned about the inevitable effect on housing demand. Some businessmen simply crave more cheap foreign labour. It seems not to occur to them that immigrants have to live somewhere.

It’s true that Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer struck a rather different note in a speech at the CBI conference on Tuesday, when he warned that Britain must learn to wean itself off migrant labour.

However, he didn’t propose an ideal number for annual immigration. Nor did he provide any plausible plan for reducing existing high levels. And, like Tony Danker — as well as every politician I can think of — he didn’t mention housing.

For all the Government’s talk of the need to control our borders after Brexit, the fact is that annual net migration hasn’t declined, and is probably now rising. I haven’t even mentioned the 40,000-odd so-called asylum seekers who have already crossed the Channel this year.

It’s true that Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer (pictured) struck a rather different note in a speech at the CBI conference on Tuesday, when he warned that Britain must learn to wean itself off migrant labour

I accept that migrants, or most of them, pay tax. They work hard, often harder than the natives. But they also need houses. The Government isn’t building enough of them, and shows no sign of ever doing so, not least because of Nimbyist opposition.

A better approach would be to make a concerted effort to induce the large number of economically inactive workers — said to have grown by 600,000 since the pandemic — to return to the labour market.

There are 5.3 million people in the UK on out-of-work benefits, even though they are part of the working-age population. The Government prefers not to describe them as unemployed, but many of them effectively are.

Some are doubtless unemployable, whether through illness or some other affliction. But many could, and should, be lured back to the labour market through a judicious use of carrot and stick.

It would be better for many of them — and for society and the economy. One obvious benefit is that, since they are already living here, there is no need to find them somewhere to live. No new homes need be constructed for these particular workers.

I appreciate this is an arduous road for any Government to take. How much easier to attract eager foreign workers — and how much more convenient for businesses, with their endless appetite for cheap and effective labour.

But one cost of continuing down the path of high immigration will be that many young people will find it hard to acquire affordable houses, since we can be certain that the Government, even when the economy recovers, is never going to build enough of them.

Ironically, of course, many of these young people, being well-meaning and open-minded, are instinctively in favour of virtually unlimited immigration. They haven’t grasped the connection between housing shortages and large numbers of people arriving here.

It’s much easier for them to blame the Government. It is admittedly at fault — but the fault is not deliberate. High levels of immigration require high levels of house building — along with the provision of adequate public services — which ministers can’t supply.

The societal price is increasing inter-generational strife, and a feeling of alienation among the young. They turn in increasing numbers away from the Tories, who offer them no hope. Not, as they will soon discover, that Labour is likely to do any better.

In theory, we could have low immigration and a less heated housing market. Or we could have high immigration and masses of new homes. What you can’t satisfactorily have is what we’ve got: high immigration and not enough houses.

Source: Read Full Article