Questlove was skeptical. In early 2019, the Roots’ drummer was approached by two Hollywood producers who claimed to have 45 hours of footage from a long-forgotten music festival in Harlem that had included performances from Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, Sly and the Family Stone, Mahalia Jackson, B.B. King, and more. Questlove, who’s renowned for his encyclopedic knowledge of music history, had never heard of the event. He had, however, become used to fellow crate-digging obsessives trying to one-up him with dubious historical tidbits.

“That’s really what I thought it was,” the drummer, a.k.a. Ahmir Thompson, recalls of his first meeting with producers Robert Fyvolent and David Dinerstein. “I thought these two were trying to gas me up for some Jimmy Fallon tickets.”

Related Stories

Rage Against the Machine, Serj Tankian, Roger Waters Sign Letter Asking Artists to Boycott Israel

Justin Bieber, Fallon, the Roots Perform 'Peaches' With Classroom Instruments

Related Stories

25 Best 'Friends' Episodes

The 80 Greatest Dylan Covers of All Time

When he watched the performances, Questlove immediately realized that not only was the footage real, but that the event it documented — the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival — was a profoundly important cultural moment that had been almost entirely lost to history.

The story that he began learning about that day started in 1967, when a local impresario named Tony Lawrence organized a series of free, weekly, Sunday-afternoon concerts in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park with the support of the New York City Parks Department. By 1969, the concerts had enough funding and cultural cachet to attract an entire summer’s worth of A-list acts from around the country. On one Sunday that June, Max Roach, the 5th Dimension, and the Edwin Hawkins Singers drew 40,000 fans to the park; one month and several Sunday shows later, 50,000 attended a bill with Stevie Wonder, David Ruffin, and Gladys Knight and the Pips.

The ’69 shows served as a crucial gathering space during a tumultuous time in black America. “The festival was a way to offset the pain we all felt after MLK,” Rev. Jesse Jackson, who spoke at the festival, told Rolling Stone in 2019. “The artists tried to express the tensions of the time, a fierce pain and a fierce joy.”

Sensing the importance of what was happening, a local television director named Hal Tulchin filmed the 1969 concerts with a professional crew, but the footage would end up sitting in his basement in suburban Westchester for nearly 50 years. “Not only was the footage forgotten, it was overlooked,” says Sasha Tulchin, Hal’s daughter. “It wasn’t wanted, and then it was forgotten.”

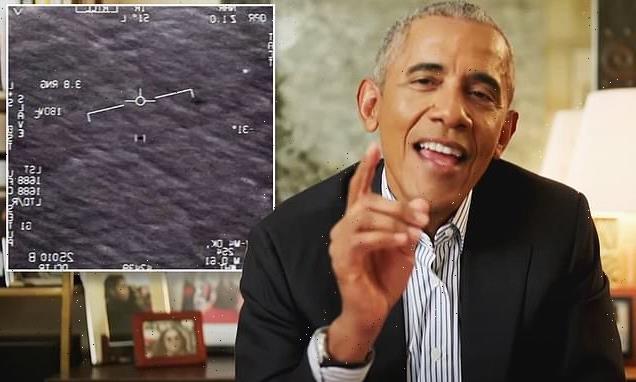

Questlove at home, 2021.

Daniel Dorsa/Searchlight Pictures

Questlove wasn’t sure he was up to the task of bringing that story to the screen at first (“Matrix bullet-dodging my own destiny,” is how he puts it). But eventually, he signed on to direct Summer of Soul (…Or, When The Revolution Could Not Be Televised), a feature-length documentary that will be released next month, 52 years after the summer when those shows took place. The movie — part concert film, part neighborhood love-letter, part interrogation of Sixties music-doc conventions — has received early raves, and the film reportedly broke a Sundance record for the largest-ever distribution sale for a documentary after opening this year’s festival.

“I thought this was going to be a quiet little arthouse film,” says Questlove. “I’m on a group chat with Just Blaze and DJ Premier and Swiss Beatz and J. Cole — 25 of my luminaries. So it was like, ‘If Jazzy Jeff and Peanut Butter Wolf think [the movie] is cool, then I’ll feel OK.’ That’s who I thought my shit was for. God had other plans.”

The origins of Summer of Soul date back to 2006, when Fyvolent, a veteran entertainment lawyer and producer, learned about the Harlem Cultural Festival footage through a friend. He spent the following decade building a relationship with Hal Tulchin, who, for various reasons, had never been able to turn his footage into a completed film. For years, Fyvolent was told by others in the industry that it couldn’t be done: too much money involved, too many rights to clear. “They were like, ‘This is going to be too expensive, given the artists involved,” says Fyvolent. “I heard that a lot.”

After signing on as director in 2019, Questlove immersed himself in the source material by playing Tulchin’s 45 hours of footage on repeat over a five-month period. “My television was like an aquarium,” he says. The process of transforming that raw footage into a feature-length film involved both creative and logistical challenges: Film production was forced to go remote during the pandemic, and the film’s narrative focus sharpened and took shape during last summer’s protests for racial justice.

From the very beginning, Questlove viewed Summer of Soul as an opportunity for a long-overdue historical course-correction. “The number one question I had was, ‘Who wouldn’t want to see this?’” he says. “Why wasn’t this written about? Who would throw this away?’”

The very fact that this historical moment had been all but forgotten became an urgent throughline in the film’s narrative. The Summer of Soul team demonstrates this, in part, by showing their interview subjects footage of the festival on camera and filming their reactions. Interspersed with the stunning performances are emotional shots of people like Harlem native Musa Jackson, who attended the festival as a five-year old, and the 5th Dimension’s Marilyn McCoo and Billy Davis Jr., being confronted with their half-century-old memories.

At first, Questlove envisioned a rhythm and feel for the film reminiscent of Sydney Pollack’s Amazing Grace, which documented Aretha Franklin’s 1972 gospel concerts in a cinema vérité style with little context. One early blueprint would have built toward a feel-good finale, with Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples leading the crowd through a rousing rendition of the civil-rights-era anthem “We Shall Overcome.”

Last year’s uprising against racism and police brutality made him dig deeper. “‘That’s how Hollywood would end the film,’” Questlove recalls producer Joseph Patel telling him. “It would let people off the hook — like, ‘See, everything’s fine, because we’re all one.’ But that’s not what’s happening now. We’re not having a Kumbaya moment. We’re protesting.”

The film’s climax now belongs to Nina Simone, who performs “Young, Gifted and Black” and offers a recitation from the Last Poets’ David Nelson: “Are you ready to smash white things, to burn buildings…Are you ready to build black things?”

“What we did as a team was interrogate our assumptions,” adds Patel. “There was this younger generation coming out in ’69 that was not about the old way of doing civil rights, it was more about black power and black consciousness.”

The total absence of “We Shall Overcome” in the final edit is just one of several moments throughout Summer of Soul that challenge the conventions of Sixties documentary-making, a genre that has been historically presented via an overwhelmingly white lens. One scene revolves around the July 20th, 1969, moon landing: After beginning with the celebratory reactions one might expect in a typical documentary on this time period, the film cuts to a very different reaction in Harlem. (“Yesterday, the moon,” an editorial in the city’s leading black newspaper, the Amsterdam News, stated. “Tomorrow, maybe us.”)

The performances in the film present a vibrant, varied vision of late-Sixties black musicality, from the chart-topping new-age pop of the 5th Dimension to the expressive jazz-rock experimentation of Sonny Sharrock and the drone-rock stylings of the Chambers Brothers. “We’ve been told that classic, Vietnam-era, iconic rock songs were by white groups, but they’re not,” says Patel.

Sly Stone performing at the Harlem Cultural Festival in 1969.

Searchlight Pictures

Even when the biggest stars in the film are onscreen, the Summer of Soul team shies away from the obvious. “Ahmir didn’t want to necessarily just pick the greatest hits,” says Dinerstein. “We don’t highlight some of the Stevie songs that everyone might know. We wanted to showcase the transition he was making as a 19-year-old artist, going from Little Stevie Wonder to Stevie.”

For Questlove, it was an angering experience to realize that, had it been given proper attention and resources at the time, a film on the Harlem Cultural Festival could have had the same wide influence as 1970’s Woodstock.

“This was supposed to come out 50 years ago, and I was supposed to see this movie as a four-year-old,” he says. “When Woodstock came out, the movie made household names out of every artist who appeared in the film. The legend of that concert wound up subsequently defining a generation…. And so, as a result, when you think of the late Sixties, you think of hippies, mud, free love, Hendrix, all of those things.”

He adds: “This could’ve been such an adrenaline boost to black music culture, and it wasn’t allowed.”

To illustrate what he means, Questlove cites a tantalizing example: Prince’s memoir, The Beautiful Ones, contains a detailed remembrance of going to see the Woodstock concert film in theaters with his father in 1970. The experience left a lasting impression on Prince, who clearly still thought about it decades later.

“His dad could have took him to see this film,” says Questlove. “Who knows what could have happened?”

Source: Read Full Article