“There’s a saying in the Ivory Coast,” says Pierre Kwenders as he slides from English to French. “Tant qu’il y a de la vie, il y a de l’espoir. ‘Where there is life there is hope.’ Hope keeps us alive. We need to dream, dream for a better world. We need to be mature enough to learn from our mistakes and keep trying to be better.”

With that forward-looking gaze, the 36-year-old singer, songwriter, DJ, actor, and style-setter simultaneously shrinks the world and expands it. With his new album, José Luis and the Paradox of Love, Kwenders connects collaborators from musical hotspots as far-flung as Kinshasa, Paris, Lisbon, Santiago de Chile, Brooklyn, New Orleans, and Seattle. His songs fuse African musical styles from across decades and countries with of-the-moment R&B sensualism, smooth-jazz ambiance, and dancefloor-directed groove. His lyrics, sung in five different languages, expose his fears and flaws while celebrating his multifaceted humanity. It’s a fluid, immersive work, vast but cohesive, elusive of genre, border, or trend. And it makes a case for the potential for anyone — and possibly everyone — to embody a more open, enlightened way to live.

Kwenders was born José Louis Modabi in Kinshasa, the capital city of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. As a kid, he absorbed the country’s dominant musical style, a generations-long trans-oceanic conversation between Africa and Cuba known as Congolese rumba. After following his mother to Montreal when he was 16, he got his first taste of performing with the Chorale Afrika Intshiyetu, a Congolese Catholic vocal ensemble. Like many young Montrealites in the 2000s, Kwenders was also drawn to the city’s colorful pop-music scene, gravitating especially to hip-hop and electronic music. The latter in particular, with its celebratory inclusivity and unbridled physicality, cracked open his imagination.

Still, Kwenders felt beholden to the expectations of straight-laced professionalism common to many immigrant families. So he attended university to pursue a degree in accounting and became a tax collector for Revenu Québec. For several years he lived as José Luis Modabi by day, Pierre Kwenders by night, borrowing his stage name from a grandfather and splitting his time between familial responsibility and personal ambition. As difficult as that period was, it proved that his drive for self-expression was unquenchable. In art he found a way to project the playful, provocative convictions he felt inside himself.

In 2014, Kwenders released his first full-length album, Le Dernier Empereur Bantou, or The Last Bantu Emperor. Its title, which Kwenders intended to send listeners googling the complex, centuries-old history of pre-colonial African peoples, was as much a statement of purpose as the luscious, synthesized soul music it contained.

“I grew up in Africa, and at school there they would teach us a lot of things about the Western world — things I didn’t really need to know about, but I’m glad that I knew. I want people to feel the same about knowing the real things about my culture,” he says. “And if I’m able to share a little bit or educate through my music, that’s the best gift.”

That same year, Kwenders launched his own monthly party called Moonshine. With no address listed to access its lineup of eclectic dance music, intrepid revelers had to text for a secret location, an under-the-radar stratagem the event still enforces as it pops up in cities from London to Los Angeles.

Touring with a band took Kwenders across Canada; traveling as a DJ took him around the world. Performing in either context, he built sets to bring listeners closer together and into a state of communal joy. He flowed freely between African musical styles — Congolese rumba, ndombolo, and soukous, along with the hugely popular Côte d’Ivoire sound known as coupé-décalé, or “rob and run” — each of which comes with distinct dance styles. Performance is storytelling, he says, and he strives to deliver an intimate, empowering experience for both himself and his audience.

“Part of the reason I became a DJ was to showcase that music,” he says. “It has always been important for me to create this bridge between African sounds and all the other sounds I keep discovering, especially in electronic music.”

That curatorial impulse came together fully in his 2017 album MAKANDA at the End of Space, the Beginning of Time. The recording process took Kwenders to Seattle, where he first worked with producer Tendai Maraire, then one-half of experimental hip-hop duo Shabazz Palaces, and guitarist Hussein Kalonji. (Maraire and Kalonji are both American-born sons of celebrated African musicians.) With its breezy saxophones, sinuous song structures, and lyrical nods to the power of love, metaphysics, and the erotic literature of Henry Miller, MAKANDA was a comprehensive rendering of Kwenders’ musical vision. It received glowing reviews and was shortlisted for Canada’s prestigious Polaris music prize.

José Luis and the Paradox of Love goes deeper. It’s more daring, more evocative, more sultry, more fun. It opens audaciously with “L.E.S. (Liberte, Egalite, Sagacite),” a ten-minute-long club banger clearly aimed at DJs. Extra intrigue comes from the song’s guest vocalist and keyboardist, Win Butler and Regine Chassagne of Arcade Fire. Kwenders met the fellow Montrealites at a benefit for Chassagne’s Haiti-based nonprofit years ago, and they’ve been supporters of his music ever since. He and Maraire took the original 30-minute cut of “L.E.S.,” co-produced by Maraire and pioneering DJ and university instructor King Britt, to Butler’s New Orleans studio for an improvisational session where the couple made their contribution.

The rest of the album is an equally intoxicating swirl of textures and rhythms. Kalonji is back along with Maraire, rotating with an international cast of collaborators: Portuguese producer Branko, Chilean producer CarloMarco, Haitian producer Michael Brun, French vocalist anaiis, New York-based beatmaker Uproot Andy, and more, all drawn into Kwenders’ orbit via his voracious ear and Moonshine affiliation. Digging into the lyrics, which Kwenders sings in French (the official language of both the DRC and Montreal), English, Lingala, Tshiluba, and Kikongo, reveals a rich reference text to African musical styles and luminaries, a mind-bending set of sonic hyperlinks. Paradox presents Kwenders as a global ambassador of self-determination, pointing the way toward a more evolved era — one in which solidarity is built on the dance floor and multiple histories can coexist within a single, enigmatic individual.

“There is no battle of identity anymore,” Kwenders says. “Pierre and José Luis are the same person. I believed I really found myself with MAKANDA, but finding myself was one thing. Then I had to tell a little bit about myself. In this album, the story that is told is José Luis’ story. It’s not Pierre’s story.” He laughs and adds, “I think Pierre’s story is still in the making.”

On Paradox, that story finds Kwenders settling long-standing internal conflicts. His mother’s voice registers approval and pride on the song “Your Dream.” (She cried when she heard it, he says.) And in the song “Religion Désir,” his love for the church choir of his youth collides with his current “weird relationship” to the Capital-C Church.

“It’s a fight between religion and desire,” he says. “I’m telling a story about this kid who goes to church and might be singing in a choir and might be finding himself being fluid or gay, but being in a church, he can’t be himself… There’s nothing wrong with churches, and it’s good to gather in a place and have a spiritual life,” he continues. “But the things we experience in church as kids — the things that we learn about ourselves, the church tells us can’t be right. We learned a lot of things that can be questionable.”

Perhaps as a gesture of reconciliation, album closer “Church (Likambo)” features vocals from Chorale Afrika Intshiyetu — the very choir he sang with as a kid. In Kwenders’ dream of the world, music is as much a bridge to common ground as a channel for radical self-expression.

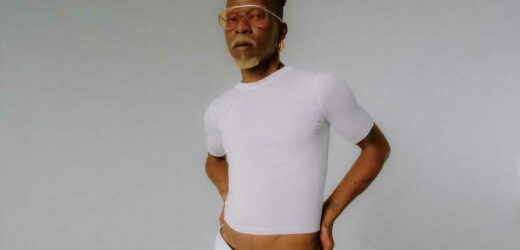

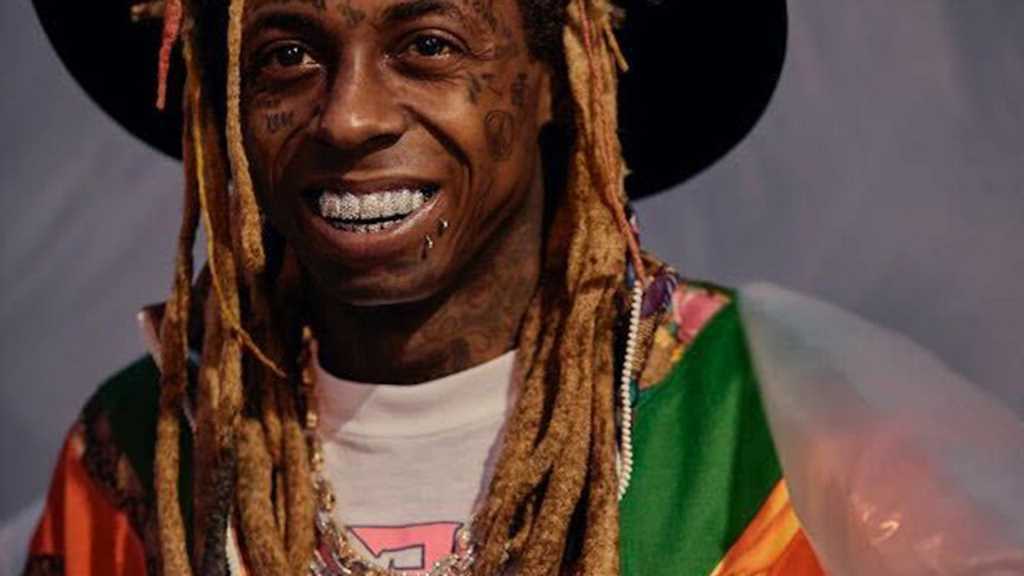

The two are inextricable for Kwenders, even in the visual aspect of Paradox. The album’s artwork and press photos depict him in a rainbow array of fashion and facial hair arrangements — fitting for an artist who’s both wildly inventive and meticulous about his image. The video for “Kilimanjaro” goes further, digitally morphing Kwenders’ face onto the bodies of iconic Black artists from across the decades as they perform in vintage video clips: Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, Fela Kuti, Miriam Makeba, Grace Jones. The effect is a winking visualization of Kwenders’ protean persona. But it also conveys a powerful will toward a new form of total creative freedom.

“I think I’m all of them, you know? I want to express the same joy those people expressed when they were onstage, on screen, when they were dancing,” Kwenders says. “And yes — when people look at me I’m a man, but there’s a lot of femininity in me. So that’s why I’m saying I’m all of that. There’s no limit to who I am, and I don’t think I will ever limit myself to expressing myself in any way.”

Source: Read Full Article