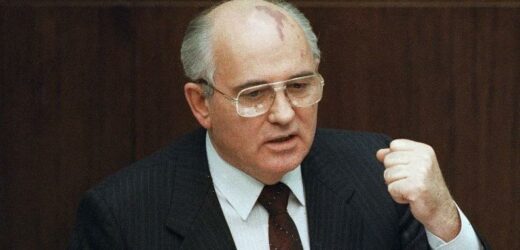

MIKHAIL GORBACHEV: March 2, 1931, died August 30 2022

Mikhail Gorbachev, the former president of the Soviet Union who has died aged 91, was the man whose reforms in the 1980s led to the collapse of the USSR and the end of Cold War; by introducing the Eastern Bloc – and the world – to the terms glasnost and perestroika, he signalled that the Marxist-Leninist political vision of 70 years earlier had been overwhelmed by market-driven capitalism.

When he was appointed general secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in 1985, Gorbachev inherited a morally corrupt system in terminal decline, and he knew that change was the only option.

Former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev has died aged 91.Credit:AP

In the spirit of glasnost (openness), he freed political prisoners; allowed open debate and multi-candidate elections; gave people wider opportunities for travel and emigration; halted religious oppression; withdrew Soviet troops from Afghanistan; curtailed Russian expansionism; and, above all, helped bring an end to the Cold War by allowing Eastern Europeans their liberty and promoting German reunification.

Working with reformers such as Eduard Shevardnadze and Alexander Yakovlev, Gorbachev showed that he was a different kind of Soviet leader – one with whom Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher, Helmut Kohl and George H.W. Bush could “do business”.

It was by no means a pain-free process and Gorbachev himself never fully understood the forces he had unleashed. As the satellite states of Eastern Europe claimed their freedom, the Soviet Union itself began to crumble as constituent republics demanded their own rights to self-determination. In August 1991 Gorbachev was temporarily ousted by a group of hardliners who held him and his family hostage at their dacha in the Crimea.

Although the plot quickly disintegrated, Gorbachev never regained his former authority. He returned to Moscow to a surprisingly warm welcome, but the country was now a very different place. In his absence the Russian president and former Gorbachev protege Boris Yeltsin, who had rallied mass opposition to the coup, had become the new national hero.

Although restored to his position as president, Gorbachev could do nothing to halt the pace of events as one republic after another declared independence. Meanwhile, Yeltsin had begun taking over what remained of the organs of Soviet power.

The final blow came on December 1 when Ukraine, the second most important republic in the Soviet Union after Russia, voted for independence. On December 17 Gorbachev accepted the fait accompli and reluctantly agreed with Yeltsin to dissolve the Soviet Union. Four days later, the leaders of 11 of the 12 remaining republics in the union preemptively accepted Gorbachev’s resignation. He left office on Christmas Day 1991.

Gorbachev was the first Soviet leader guided by realism, not ideology, yet while he loosened the control of the centre, his purpose had been to save the Soviet Union, not destroy it, and he remained wedded to the communist ideal.

Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, left, and Britain’s Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher pose for a picture in London, 1984.Credit:AP

In his memoirs, published in 1996, he wrote: “Communist ideology in its pure form is akin to Christianity. Its main ideas are the brotherhood of all peoples irrespective of their nationality, justice and equality, peace, and an end to hostility between peoples.”

To the end of his life he clung to the belief that there is an enlightened version of communism which could withstand the temptations of totalitarianism.

So by any objective standard, Gorbachev failed in his career as a politician and he ended his days a disappointed, marginalised figure. Yet, were it not for him, the Soviet Union might still exist. The great irony is that Gorbachev sought neither the demise of communism nor the break-up of the Soviet Union yet he became seen as a hero in the West for having engineered both.

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev was born into a Russian peasant family on March 2, 1931 at Privolnoye, a village in the Stavropol region of the North Caucasus. His grandfather was a party member and became chairman of the first collective farm set up in Privolnoye in 1931, though this did not prevent his being arrested on false charges in the 1930s and sent into internal exile in Siberia.

His father was also a communist, and worked as a machine operator in a local tractor station until the Wehrmacht invaded the area in 1942.

By the age of 15 Mikhail was driving a combine at that same tractor station, and in 1949, after a record grain harvest, was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labour – a rare distinction for an 18-year-old. A member of the Komsomol (Communist Youth League), he was elected a candidate member of the Communist Party in 1950, becoming a full member in 1952.

His good party record and school grades gained him a place at Moscow University, where he chose to study law. This was a fairly original choice in those days: law still retained a certain level of academic excellence and also provided undergraduates with training in rhetoric.

During his undergraduate days, from 1950 to 1955, Gorbachev shared a room with Zdenek Mlynar, who later came to prominence during the Prague Spring of 1968. Mlynar regarded Gorbachev as a born leader, but other fellow students were not so complimentary, pointing out his ruthless ambition and his half-hearted opposition to the anti-Semitic excesses of the latter Stalin years.

Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and his wife Raisa wave to a crowd during their visit in Paris, France, 1989.Credit:AP

Gorbachev does not appear to have been offered a Moscow job on graduation, and he certainly never practised law. He returned instead to his family home in the northern Caucasus and entered Komsomol work.

The next year, 1956, was a turning point in his life. He became leader of the Komsomol at Stavropol, and married Raisa Titorenko, a rail-worker’s daughter whom he had met at a ballroom dancing class at university in Moscow. In 1957 Raisa bore their only child, Irina, and then found a job as a teacher in the local polytechnic.

Over the next four years, from 1958 to 1962, Gorbachev served as deputy head of the propaganda and agitation department of the Stavropol krai (provincial) Komsomol committee, then as second secretary and finally as first secretary.

In so doing he became a member of the Stavropol krai Party (kraikom) bureau. His rapid rise through the ranks was partly the result of good fortune, in coming into contact with officials who valued his organisational and propaganda skills.

In 1962 he abandoned his Komsomol work and became a party organiser. He was in charge of about 30 kolkhozy and sovkhozy – which he brought together to form a territorial association. It was a risky step, but the weather was kind and production soared.

Gorbachev spent only one harvest in the field before being appointed head of the department of party organs, the Stavropol kraikom. This was a key post, since it gave him a say in all appointments in the krai. Stavropol, with its many spas and sanatoriums, was frequented by many high-ranking party officials, so he also came into increasing contact with Moscow and the KGB. Among those with whom he liaised at that time was Yuri Andropov, the future party leader.

When Brezhnev replaced Khrushchev as party leader, Fyodor Kulakov, the first secretary at the Stavropol kraikom, moved to Moscow and became Central Committee secretary for agriculture in 1965.

The new first secretary of the Stavropol kraikom, Efremov, was not regarded as a Brezhnev man, and lasted only four years, before, in 1970, Gorbachev – who had in the meantime risen to become second secretary of the Stavropol kraikom – was appointed in his place.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, right, talks with former Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev at the Castle of Gottorf in Schleswig, northern Germany, 2004.Credit:AP

The post of first secretary, ex officio, qualified Gorbachev for membership of the Central Committee (CC) of the CPSU. He was duly elected a full member at the XXIV Party Congress in 1971. By the age of 40 he was one of the top 300 communists in the USSR.

In 1970 Gorbachev was also elected to the USSR Supreme Soviet. He served as a member of the commission on conservation from 1970 to 1974; as chairman of the commission on youth affairs from 1974 to 1985; and as chairman of the commission on foreign affairs in 1984-85.

His breakthrough to national party affairs occurred in 1978, when he succeeded Kulakov as CC secretary for agriculture. The next year he was elected a candidate member of the Politburo, and the year after that a full member.

Gorbachev’s next big promotion came in 1982, when Brezhnev died and was succeeded by Andropov, himself mortally ill. The new leader had a high opinion of Gorbachev’s talents and made him CC secretary for the economy, cadres and agriculture. Gorbachev used that post to forge an ever stronger profile within the Central Committee. The master tactician was already in the making; he managed to push through his own radical ideas without alienating too many powerful colleagues.

On Andropov’s death he was narrowly pipped to the top post by Konstantin Chernenko, who was also mortally ill. But he soon emerged as Chernenko’s de facto deputy, and, as such, added ideology and global communist affairs to his secretarial brief.

On March 11 ,1985, Gorbachev successfully fought off challenges by Grigory Romanov and Viktor Grishin and was elected general secretary of the CPSU.

As was customary for a Soviet leader, he immediately excoriated the failings of the previous leader. He dismissed the Brezhnev era as a period of “stagnation”, declaring that the Marxist-Leninist model in the Soviet Union was in irreversible decline: the country had failed to develop a viable socialist alternative to market capitalism.

But Gorbachev’s first year in power taught him that the crisis was not merely an economic one. Economic reform, he decided, could not take place without first reforming the political structures: thus perestroika was launched, and that movement was followed in its turn by glasnost.

These reforming programs were intended to overcome the apathy of the Soviet population, as well as to encourage criticism of the bureaucracy. This would provide him with, among other things, ammunition in his battle to rid himself of the diehard Brezhnevite apparatchiks.

Away from home, Gorbachev was fast developing into one of the megastars of world politics. A man whose speeches had been as dreary as Brezhnev’s turned into an eloquent propagandist for a complete restructuring of the Soviet Union’s relations with the outside world as well as a jovial, thoughtful and bantering adversary for Western leaders.

He developed an especially warm rapport with the British prime minister Margaret Thatcher who relished their lively political jousts. On one occasion in the Kremlin, while their respective officials kicked their heels outside, they argued for nine solid hours, leaving Thatcher no time to change into evening dress for the Kremlin banquet that evening.

Gorbachev’s wife, Raisa, also played a vital supporting role in his elevation abroad. In marked contrast to her silent, stodgy predecessors, she revelled in her role as First Lady. Her husband called her “my general”, and said he discussed everything with her, even the most sensitive political issues. Well-educated, smart and always well turned-out, Raisa seemed a walking embodiment of the virtues of a transformation to a capitalist economy.

Gorbachev was devastated when his wife Raisa died in 1999 after a long struggle with leukaemia, and admitted that for a time he had flirted with thoughts of suicide. In 2006 he established the Raisa Gorbachev Foundation, a charity dedicated to helping cancer patients and funding research to find a cure.

Mikhail Gorbachev’s daughter survives him.

The Telegraph, London

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in National

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article