Here’s the thing about bank robbery movies: No one ever roots for the bank. The tellers rarely seem like real people; the institutions don’t need the money; the insurance companies take the hit. But even if our sympathies naturally gravitate toward the lawbreakers, seldom has the stick-up guy seemed more sympathetic than the one in director Abi Damaris Corbin’s Sundance-launched feature debut, “892,” based on a recent case in which the crime was really a cry for help.

On July 7, 2017, Brian Brown-Easley walked into a Wells Fargo in Marietta, Ga., and handed the clerk a note that said, “I have a bomb.” But what he meant was “I have a message.” Brown-Easley wasn’t looking to take the bank’s money. He demanded just $892.34 — the same amount that the Dept. of Veteran Affairs had withheld from his last disability check. But even more importantly, he wanted an audience, causing a scene and taking hostages so that the world might hear his frustration, seemingly directed at the VA but clearly aggravated by the whole broken bureaucracy.

These days, there’s a word for such stunts: Some consider it “protest,” others “terrorism,” and your enjoyment of “892” may depend on which camp you fall into. Damaris Corbin and co-writer Kwame Kwei-Armah don’t pretend that Brown-Easley wasn’t wrongheaded in his approach. But they also recognize how disenfranchised honorable men can be made to feel by the same system they served. Rash and self-destructive as Brown-Easley’s actions may have been, “892” presents the incident as an act of self-respect — the desperate stab by an ex-Marine, ex-husband, all-around-exhausted 33-year-old man to preserve some shred of dignity.

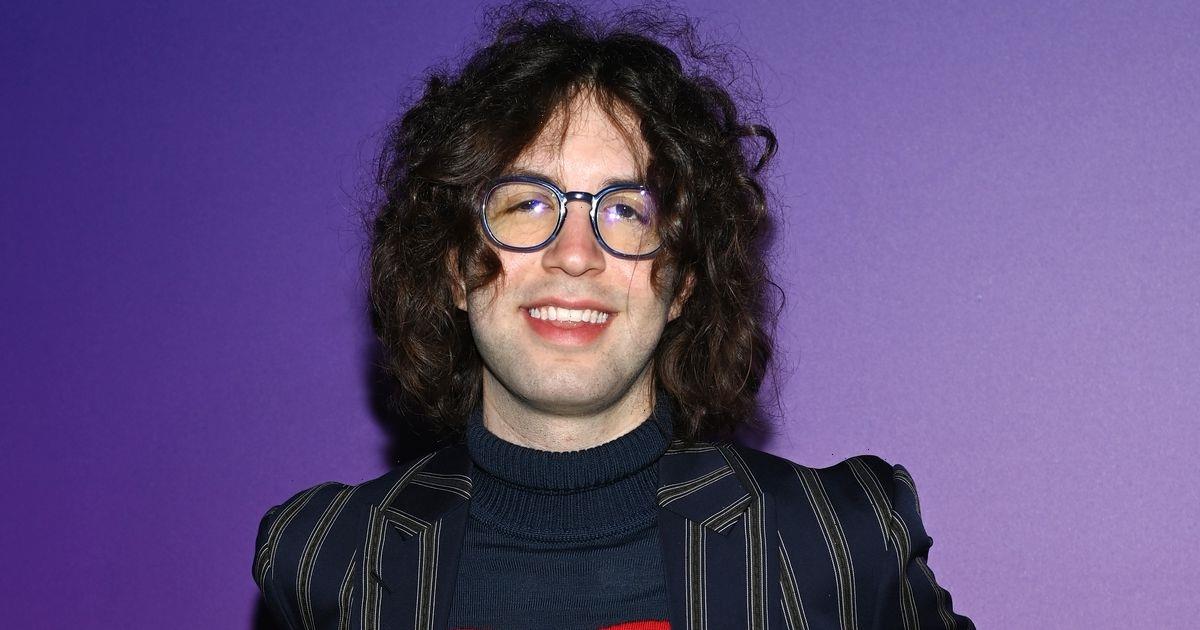

In the film, Brian is embodied by John Boyega — for many still the fresh-faced actor of “Star Wars” and “Attack the Block” fame, although he’s proven himself to be so much more in recent years. Boyega is a serious, politically engaged artist with a capacity to play tough, troubled characters, and “892” marks a potential turning point for him. Boyega disappears behind Brian’s loose hoodie and rimless reading glasses. His body language is broken, his right cheek badly bruised. He fidgets nervously, like a character out of “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” Boyega is the most interesting thing about the movie — specifically, the way he portrays this tragic, psychologically damaged individual fighting for what matters to him — although it’s also noteworthy for featuring Michael Kenneth Williams’ final performance as the hostage negotiator.

Brian has done his military service; he’s trying to do right by his daughter, Kiah (London Covington). “892” doesn’t belabor his backstory. In the opening scene, we hear him talking to Kiah on the phone. She wants a puppy. She doesn’t realize that he’s down to the last minutes of his pay-as-you-go mobile plan, that he’s living out of a hotel room but effectively homeless. Brian’s mind is already made up, and though he hesitates outside the Wells Fargo the day his life changes forever, the pause is more for dramatic effect than any kind of self-doubt.

From the moment Brian steps inside the bank, it’s clear this isn’t a normal bank robbery. He hardly seems to have a plan; he might not even have a bomb, despite what he says. Brian looks almost apologetic as he asks for a pen and passes his scribbled threat across the counter. (Some may be reminded of the gag from Woody Allen’s “Take the Money and Run” when the teller struggles to decipher the note: “Apt natural. I’m pointing a gub at you.”)

Brian is described here as the kind of person who wouldn’t hurt a fly, and “892” shows him letting practically everyone exit the building — all but two managers (Nicole Beharie and Selenis Leyva, both totally believable), whose fear melts into forgiveness as the ordeal drags on. Brian instructs one to call 911, and when the authorities stall instead of connecting him with a negotiator, he rings the local TV network, hoping a producer (Connie Britton) will air his complaint with the VA.

We want to hear what Brian has to say. In most cases, it may be wrong to give criminals a platform to rant, but here, it’s pretty much the point. Williams’ character, Eli, happens to be an ex-Marine as well, and the two share a human connection during their short interaction. We recognize the type: the sympathetic cop (think Harvey Keitel in “Thelma & Louise”), when every other authority figure seems to want the perp taken out. Among the carnival of local police, FBI agents, GBI agents and TV reporters that forms around the bank, several snipers take aim — and indeed, audiences grow familiar with the sight of Boyega’s head in the crosshairs.

Damaris Corbin and DP Doug Emmett shoot “892” like a studio heist movie (Spike Lee’s “Inside Man” seems an obvious reference), dialing down the range of colors to blues and blacks, covering the action via moving, restless cameras. This is not an act of documentary reenactment so much as a tense, speculative drama, imagining what this man must have gone through during those hours, and how his actions rippled out to affect others’ lives. According to “892,” Brian knew what his fate would be. (Spoiler alert.) Before entering the bank, he recognized how situations like this end for Black men in America. He chose to make an example of himself. The movie asks us to decide whether he was a martyr or a mental case for taking such a stand.

Source: Read Full Article