If we didn’t know it already, the current seven-day lockdown demonstrates the COVID-19 pandemic is far from over. What is becoming clear as the rest of the economy roars back to life is that the impact of coronavirus is being disproportionately felt in Australia’s CBDs and the City of Melbourne in particular, as PricewaterhouseCoopers modelling shows.

Which is why it is hard to imagine a worse time and place to put an injecting room in the centre of Melbourne. Yet bizarrely this is what the Andrews government is going to do.

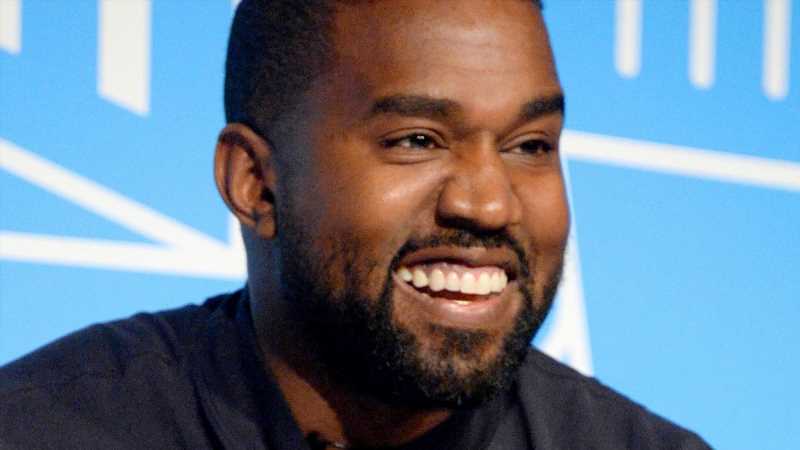

Melbourne City Council has voted in support of a safe injecting facility in the CBD. It is expected to be located somewhere opposite Flinders Street Station.Credit:Joe Armao

That’s why I moved a motion on Tuesday night calling for Melbourne City Council to reject the plan anywhere in the City of Melbourne. It was defeated but the fight by the residents and businesses whose lives have been disproportionately impacted by COVID will go on.

Advocates for a second injecting room claim they save lives although there was no decline in the number heroin-related deaths in the City of Yarra in the year after the Richmond injecting room opened compared to the three years prior. Some modelling suggests that between 21 and 27 deaths were avoided over the first 18 months of the injecting room’s operation, but the state government’s review noted it is not possible to say with certainty how many people would have died without the facility.

The evidence is far from clear. Even if there are no deaths in the injecting room – it would be extraordinary it that wasn’t so – the position outside on the street isn’t improved.

Indeed, in the 12 months after the state government opened its first injecting room in North Richmond in June 2018, there were more heroin-related deaths in the one kilometre around it than there were in the 12 months prior to its opening.

Inside the safe injecting room in North Richmond.

That’s a finding of the state government’s own review into the injecting room, which also found significantly fewer residents and businesspeople reported feeling safe walking alone during the day and after dark. The reasons offered included concerns about violence and crime, public visibility of drug use and drug deals, safety concerns for their own children and schoolchildren, aggressiveness and unpredictability among people who use drugs and discarded syringes in public places.

Common sense tells you the situation on the street goes downhill when a safe injecting room opens.

Users are more likely to buy their drugs nearby than to bring them from home and risk being caught on their travels. To service these customers a street drug market springs up around the destination.

A survey of Victoria Police working around the North Richmond facility found 77.5 per cent had observed “significantly more” people who appeared to be buying or selling drugs after it was opened.

Drug paraphernalia left by users at the Richmond public housing estate, near the safe injecting room.

Equally unsurprisingly, not all those drug users made their way to the injecting room. In the first 10 months after it opened, the number of inappropriately disposed syringes collected in the surrounding area increased by 27 per cent compared to the previous 10 months.

Nor is that all. Again – equally – unsurprisingly – 67.5 per cent of police surveyed observed “significantly more” people who appeared to be under the influence of drugs in the North Richmond area after the injecting room was established.

Ask yourself if this is what we want in the heart of our city and why Melbourne’s restaurateurs and shop owners – now enduring their fourth lockdown – should be made to put up with it.

Prior to COVID-19, the City of Melbourne was the engine room of the Victorian economy with a gross local product totalling more than $104 billion. However, the impacts of the pandemic have been disastrous with PwC projecting the economy would lose 79,000 jobs and up to $110 billion in output over the next five years.

Nationally, the City of Melbourne is the local government area with the biggest decrease in retail and recreation activity compared to the pre-COVID baseline period. About 20 per cent of retail and hospitality shops in the City of Melbourne remain unoccupied.

It is a bleak but unsurprising picture for anyone reading this on their couch.

The economy of the central city relies heavily on a transient daily population. COVID-19 has led to a significant reduction in daily visitor numbers and even when restrictions were lifted commuter activity remained depressed.

It is difficult to imagine visitors flocking back to our beautiful city if the experience in North Richmond is repeated.

There is also a broader concern about the message an injecting room sends by sanctioning criminal activity. School children changing trams and trains don’t need to see drug trafficking and young children on their way to a city childcare centre shouldn’t be stepping over discarded syringes.

Ominously this week the Police Association noted a significant spike in crime near the North Richmond injecting room in its first year and warned of a surge in violent incidents in the CBD if the injecting room proceeds. They also warned against believing claims the Victoria Police will have the capacity to meet predicted increases in crime with a highly visible policing approach.

We all know of cities with no-go zones because crime and drug use has overtaken their streets. Why would we take that risk?

Roshena Campbell is a Melbourne City councillor and commercial barrister. The views expressed are her own and not those of Melbourne City Council.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article