One of the most important differences between the Liberal Party and the Labor Party is a historical one. Labor traces its roots to the trade union movement of the late 19th century; it does not point to any one great figure as its founder. The Liberal Party, by contrast, is unquestionably the creation of a single man, Robert Menzies – its founder and longest-serving leader and Australia’s longest-serving prime minister. Both sides of politics acknowledge this: Paul Keating, in a savage speech, once spoke of his desire “to destroy Menzies’ creation”.

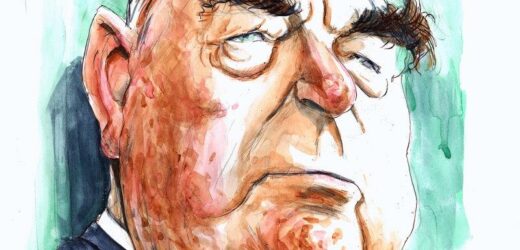

Liberal Party founder Sir Robert Menzies with his portrait painted by Ivor Hele in 1954.Credit:

The political machine Menzies assembled from the wreckage of non-Labor politics in the mid-1940s became Australia’s most successful party – 19 wins out of 30 elections since 1946, including seven of the last 10. And so, whenever the party engages in one of its periodic bouts of soul-searching about its future direction, it is invariably Menzies whom the protagonists of every point of view invoke to their cause. His posthumous approval is the ultimate court of appeal.

Recently, we have seen right-wing elements attempt to conscript Menzies’ name and memory to justify positions which are actually antithetical to his beliefs, and to the purposes for which the Liberal Party was founded. Whether this was done through ignorance or deliberate falsehood – I suspect an unattractive combination of both – it was much in evidence at a conference of “conservative” activists in Sydney recently, modelled on the Trump-influenced American Conservative Political Action Committee – or CPAC. The star turn at the conference was chief Brexit rabble-rouser Nigel Farage. A number of prominent National Party politicians, including Matt Canavan, also spoke, although the only sitting Liberal politician given a speaking slot was an obscure South Australian backbencher in the Cory Bernardi mould.

So let us set the record straight about what Menzies believed and what he meant the Liberal Party to be. Nick Cater, Director of the Menzies Research Centre, has written, accurately: “The Whigs, not the Tories, were Menzies’ political antecedents; his thinking drew from classical liberalism, the post-Enlightenment reforming forces in Britain and Australia in the 19th and early 20th centuries.”

Two great political figures influenced Menzies most. First was Gladstone, the titan of late 19th-century British politics. The Menzies family were avowed Gladstonians; his brother was even named in honour of the great man. The other was the early Australian prime minister Alfred Deakin. Those who served in cabinet with Menzies – including Harold Holt and Paul Hasluck – attested in public lectures in the years after his retirement that Menzies saw himself as Deakin’s political legatee. Both Gladstone and Deakin were anti-socialist progressives.

Of the many speeches in which Menzies set out his political philosophy, the most instructive is a series of radio broadcasts which he gave between late 1941 and 1943. Taking their name from the most famous of them – “The Forgotten People” – they are the urtext of the Liberal Party. They reveal not just the breadth and depth of Menzies’ thinking, but his enlightened humanity.

For instance, in his broadcast on April 10, 1942 (“Hate as an Instrument of War Policy”), he criticised the Curtin government for using racial prejudice as a propaganda tool against Japan. Its sentiments are those of a tolerant, civilised and liberal man – and, given that it was delivered shortly after the fall of Singapore, when Australians lived in dread of Japanese invasion, a brave one as well.

When Menzies formed the Liberal Party in 1944 – as his contemporary notes and correspondence reveal – he very deliberately avoided naming it the “Conservative Party”. He explained why in his memoirs (in a chapter entitled “The Revival of Liberalism in Australia”): “We took the name ‘Liberal’ because we were determined to be a progressive party, willing to make experiments, in no sense reactionary but believing in the individual, his rights, and his enterprise, and rejecting the Socialist panacea.”

Of course, there was much that was conservative about Menzies – in the best sense of that much-misused word. This was most obvious in his traditionalism, in particular his sentimental devotion to British institutions. As John Howard has pointed out in his wise recent book of essays A Sense of Balance, there is no inconsistency between classical liberalism and institutional conservatism. Menzies embodied both as, at its best, the Liberal Party does.

What Menzies absolutely was not, was an ideologue. It was of the essence of his liberalism that he valued the freedom of the individual; it was of the essence of his conservatism that he despised the doctrinaire. In his last speech to the Liberal Party Federal Council, in 1964, surveying his long public life, he said: “We have no doctrinaire political philosophy. Where government action or control has seemed to us to be the best answer to a practical problem, we have adopted that answer … But our first impulse is always to seek the private enterprise answer, to help the individual to help himself, to create a climate, economic, social, industrial, favourable for his activity and growth. … As the etymology of our name ‘Liberal’ indicates, we have stood for freedom.”

It is necessary for a political party recently cast into opposition to debate its future direction. For the Liberal Party, that will appropriately mean a discussion of where it orients itself on the political spectrum: does it become more moderate, or more right wing? But there is a danger, too, that such debates can be hijacked by political charlatans to misrepresent the party’s history and attack its core values. That has sometimes seen the misappropriation of the name of its great founder – the man who created the Liberal Party for the explicit purpose of enshrining progressive classical liberalism as the anti-socialist alternative in Australian politics – to justify ideologically extremist positions he would have plainly detested.

At the CPAC conference, one prominent participant – a federal vice-president of the Liberal Party, no less – said that “we should rejoice” that a number of Liberal seats had been lost to Labor and the teals. Those included MPs like Tim Wilson, Trent Zimmerman and Jason Falinski, classical liberals in the Menzies tradition, who were described as “lefties”, whose defeat was “a good thing”.

It isn’t just Paul Keating who wants to destroy Menzies’ creation.

George Brandis is a former Australian high commissioner to the United Kingdom and Liberal Party senator.

The Opinion newsletter is a weekly wrap of views that will challenge, champion and inform your own. Sign up here.

Most Viewed in Politics

From our partners

Source: Read Full Article